Ever wonder why that particular initiative of yours never got traction? Organizational politics kills more initiatives than people realize, and happens both at leadership and individual contributor levels. Understanding some of the dynamics can help to better navigate the terrain.

Three organizational layers and their experiences

- The individual contributor: You solved a major, recurring customer problem. They praised you, and so did all the stakeholders. Your manager thought this could be scaled and got other units interested. You even made a presentation to the top brass. But somewhere along the way, it got killed, or more like atrophied. Meanwhile they're asking you to work on a brand new “initiative” the CEO is pushing.

- The middle manager: You don’t understand why your teams are getting lost in the details. Why can’t they see the forest from the trees? And why is the CEO running after this new shiny thing? Can she not see the reality on the ground?

- The CEO: You brought in the top consultants who proposed a viable, “proven” solution to a vexing company wide problem. But it never gained traction or even acceptance at some levels. Everyone is back to their old ways of doing things. Clearly, the execution faltered — it always does, it’s never the strategy. Perhaps you should’ve considered the consultant’s add-on implementation package instead of relying on your teams.

And the cycle goes on. Sounds familiar?

Two diverging approaches

The practical wisdom of employees ... will never reach the manager who is convinced that his position puts him above the need to listen to other’s opinion and advice.

— Konusuke Matsushita in My Management Philosophy

Innovation is probably one of the most overused buzzwords in the corporate world, and yet in practice, organizations actively prevent it. One reason this happens is due to the constant tension, and often disconnect, between strategies that get pushed down from the top versus those that rise organically from the bottom up.

The frontline folks, along with first and middle management, are typically well aware of emergent local issues. Meanwhile, the top tier of management is typically conversant with macro challenges affecting the entire organization.

Many of these conflicts are simply the nature of the beast. The mistake however is to rely on any one of these exclusively.

The dynamic dialectic

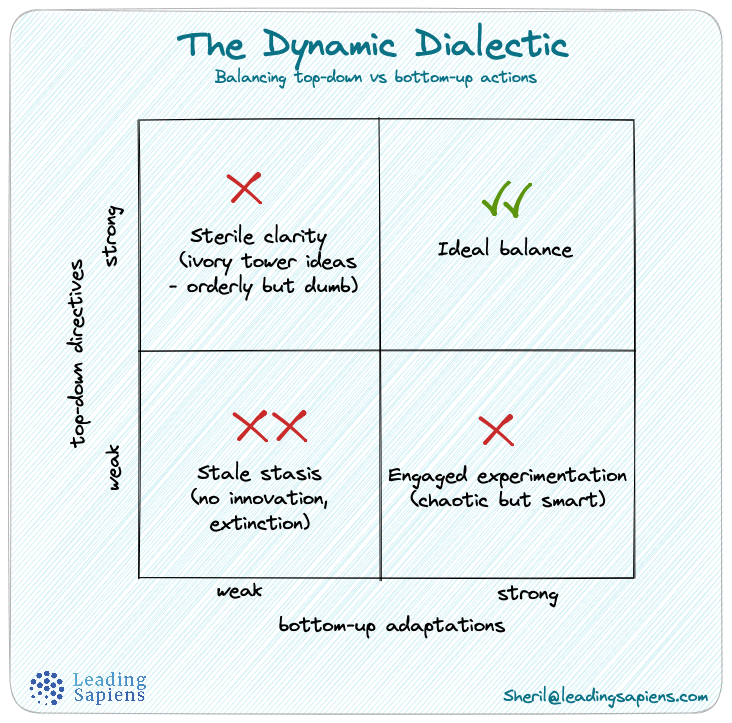

Intel CEO Andy Grove, writing in Only the Paranoid Survive, called this balancing of top-down and bottom-up approaches to strategy and innovation, “The dynamic dialectic”. He identified it as a key attribute of companies that survive and come out winning on the other side of strategic inflection points.

It seems that companies that successfully navigate through strategic inflection points have a good dialectic between bottom-up and top-down actions.

Bottom-up actions come from the ranks of middle managers, who by the nature of their jobs are exposed to the first whiffs of the winds of change, who are located at the periphery of the action where change is first perceived (remember, snow melts at the periphery) and who therefore catch on early. But, by the nature of their work, they can only affect things locally….

Their actions must meet halfway the actions generated by senior management. While those managers are isolated from the winds of change, once they commit themselves to a new direction, they can affect the strategy of the entire organization….

The best results seem to prevail when bottom-up and top-down actions are equally strong. [1]

This dynamic dialectic is a must. The wisdom to guide a company through the valley of death cannot as a practical matter reside solely in the heads of top management. If senior management is a product of the legacy of the company, its thinking is molded by the old rules. If they are from the outside, chances are they really don’t understand the evolving subtleties of the new direction. They must rely on middle management.

Yet the burden of guidance also cannot rest solely on the judgment of middle management. They may have the detailed knowledge and the hands-on exposure but by necessity their experience is specialized and their outlook is local, not company-wide. [1]

What we needed was a balanced interaction between the middle managers, with their deep knowledge but narrow focus, and senior management, whose larger perspective could set a context. The dialectic between these two would often result in searing intellectual debates. But through such debates the shape of the other side of the valley would become clear earlier, making a determined march in its direction more feasible. [1]

Debate versus determined march

There are two distinct phases, each with its particular characteristics and strategy:

- Debate: when the strategy is not clear, still emerging, and primarily relying on wide experimentation.

- Determined march: when some sort of strategy has emerged as a winner from the various experiments, and now it’s time to double down and focus resources in that direction.

Recognizing the swing of the pendulum from one phase to the other and changing tact accordingly is a key competence.

An organization that has a culture that can deal with these two phases—debate (chaos reigns) and a determined march (chaos reined in)—is a powerful, adaptive organization. … Such an organization has two attributes:

1. It tolerates and even encourages debate. These debates are vigorous, devoted to exploring issues, indifferent to rank and include individuals of varied backgrounds.

2. It is capable of making and accepting clear decisions, with the entire organization then supporting the decision.

Organizations that have these characteristics are far more strategic-inflection-point-ready than others. … While the description of such a culture is seductively logical, it’s not a very easy environment in which to operate, particularly if you are a newcomer to it and are not familiar with the subtle transition in the swings of the pendulum. [1]

Each of these opposite ends of the spectrum have their unique characteristics. Management’s role is to enable the dance rather than artificially dictate, or inadvertently squelch what’s emerging.

If the actions are dynamic, if top management is able to alternately let chaos reign and then rein in chaos, such a dialectic can be very productive. When top management lets go a little, the bottom-up actions will drive toward chaos by experimenting, by pursuing different product strategies, by generally pulling the company in a multiplicity of directions.

After such creative chaos reigns and a direction becomes clear, it is up to senior management to rein in chaos. A pendulum-like swing between the two types of actions is the best way to work your way through a strategic transformation. [1]

Carlson’s law

One attribute of top-down strategy, especially when disconnected from reality on the ground, is that it ends up being sterile and lacking engagement at lower levels.

Meanwhile, bottom-up approaches while chaotic are often dynamic and smart. They’ve emerged from the cauldron of numerous realtime adaptations in the thick of action. But they also need to be nurtured, and given encouragement and support to roll them out on a larger scale in order to have any impact.

Thomas Friedman calls this variance between the two approaches, Carlson’s Law:

Innovation that happens from the top down tends to be orderly but dumb.

Innovation that happens from the bottom up tends to be chaotic but smart. [2]

The notion of the lone mad scientist or the singular, ground breaking idea in innovation is pervasive. What gets missed is that many novel ideas often emerge in the day-to-day engagement with the mundane details of a challenge. And the people who have the most engagement are folks on the front lines.

“People think innovation is the idea you have in the shower,” said Ernie Moniz, the physicist who heads MIT’s Energy Initiative. “More often it comes from seeing the problem. It comes out of working with the materials.”

To be sure, there is some pure innovation—coming up with a product or service no one had thought of before. But a lot more innovation comes from working on the line, seeing a problem, and devising a solution that itself becomes a new product. That is why if we don’t retain at least part of the manufacturing process in America, particularly the high-end manufacturing, we will lose touch with an important source of innovation: the experience of working directly with a product and figuring out how to improve it—or how to replace it with something even better. [2]

Increasing organizational complexity also means increasing specialization and resulting silos, where skills and knowhow are concentrated in certain people and teams. This means no one person or team has all the answers, and thus one more reason to enable innovation at every level of the organization rather than a select few.

In the past, companies had ‘‘innovation centers” off in the woods, where big-thinking R&D teams devised new things that were then produced on the assembly line. Some companies still have such centers, but others are opting instead for continuous innovation that includes frontline workers as well as top management.

Now every employee is part of the process… The assembly-line worker today not only has more information than ever before, but also the capacity to communicate what he or she is learning instantly to upper management and throughout the company. [2]

The role of the leader

From this perspective then, what is the role of a middle manager, or a VP? Curtis Carlson, CEO of SRI International, puts it this way:

We had a group visiting SRI from Japan… and one of them asked me: ‘How many big decisions do you make every day?’ I said, ‘My goal is to make none of them. I am not the one interacting daily with the customer or the technology. My employees are the ones interacting, so if moving ahead on a project has to wait for me to decide, that is too slow. That does not mean I don’t have a job. My job is to help create an environment where those decisions can happen where they should happen—and to support them and reward them and inspire them.’”

Carlson said he thinks of himself more as “the mayor” of his company, orchestrating all the departments and listening to his constituencies, rather than as a classic top-down CEO. [2]

The four star general Stan McChrystal calls this style of leadership as gardening, in contrast to that of the all-knowing chess master.

It's a mistake to dismiss this as merely a more “democratic” way of leading and managing. It’s in fact almost a requirement to survive rapidly changing conditions, requiring constant adaptation and adjustment, that almost every modern organization faces today.

Continuous innovation is not a luxury anymore—it is becoming a necessity. In the hyper-connected world, whatever can be done, will be done. The only question for a company is whether it will be done by it or to it: but it will be done. A breakthrough product, such as the iPhone, instantly generates competition—the Android. Within months, the iPad had multiple competitors.

So a company that does not practice constant innovation by taking advantage of every ounce of brainpower at every level will fall behind farther and faster than ever before. [2]

Adjusting for biases at each level

Understanding the stage of your initiative along with the priorities of other stakeholders, is equally critical for success as is the logic of your approach.

For the individual contributor, it might be to tie the proposed solution to the larger organizational picture. For the middle manager, it might be to orchestrate competing priorities. For the CEO, it might be to align with ground level reality — almost every episode of Undercover Boss is an example of this disconnect.

Each level of the organization has its own version of myopia. Adjusting for biases specific to our narrow focus and level can greatly increase chances of success.

Related reading

- Strategy and innovation often emerge in the process of active coping and adapting to real-time conditions and situations. In that context, it’s more akin to Tetris rather than the traditional notion of strategy as chess.

- The idea of the big bold bet while sounding enticing is often more romantic than practical. In contrast, an emerging strategy of focusing on small wins can be a more effective way when operating in ambiguous, complex domains that require novel approaches.

- As a manager or executive, how do you make sure you are conversant with the realities on the ground? It's simple but not easy — managing by wandering around or MBWA.

Sources

- Only the Paranoid Survive by Andy Grove.

- That Used to Be Us by Thomas Friedman, Michael Mandelbaum.