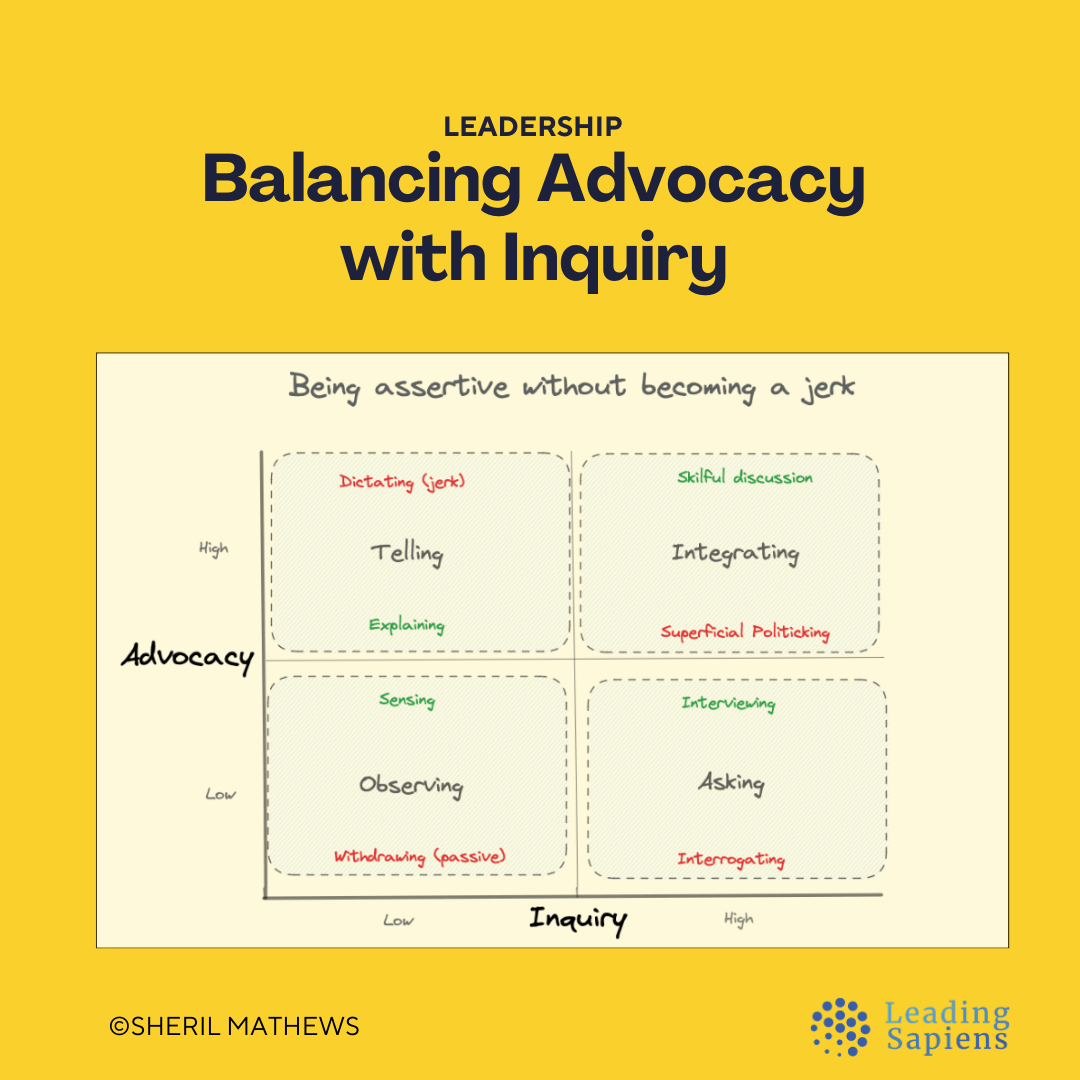

Can balancing advocacy with inquiry be implemented at an organizational level? Turns out, you can.

Roger Martin is one of the world's foremost experts on strategy and a former dean of the Rotman School of Management. He shares an example at P&G where giving equal importance to inquiry in addition to the default mode of advocacy was a key driver in implementing new strategies and adopting the behaviors to support them.

He calls it "assertive inquiry".

What is assertive inquiry

In The Opposable Mind, Martin defines Assertive Inquiry as:

The third important tool for the integrative thinker is assertive inquiry. Integrative thinkers use it to explore opposing models, and in particular, models that oppose their own.

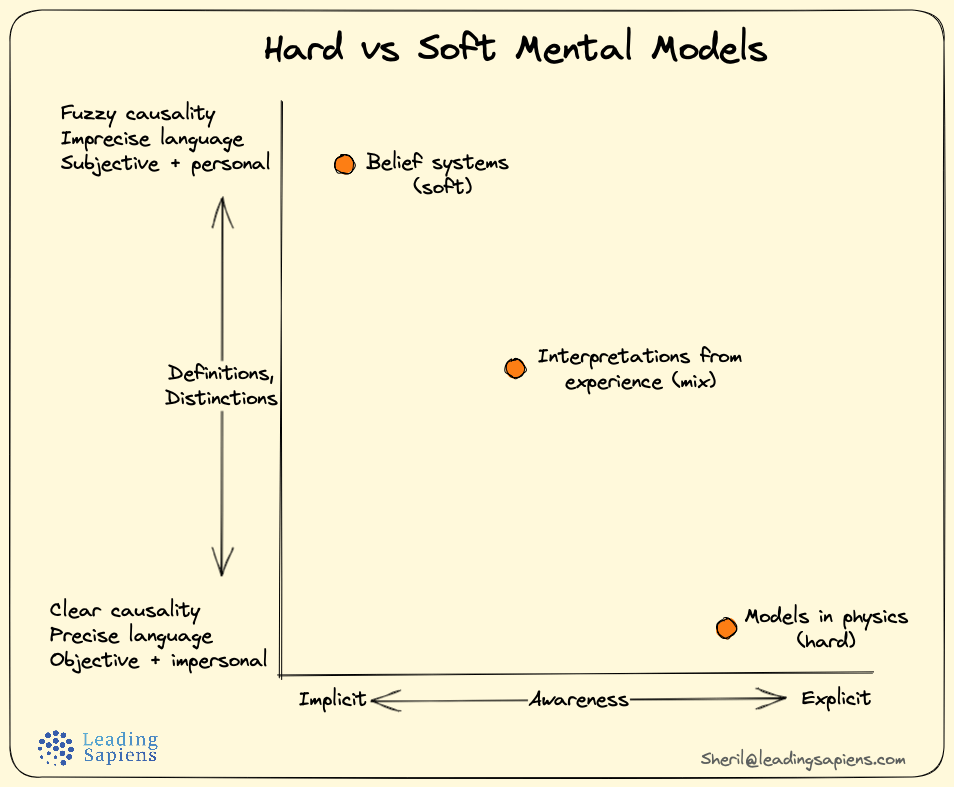

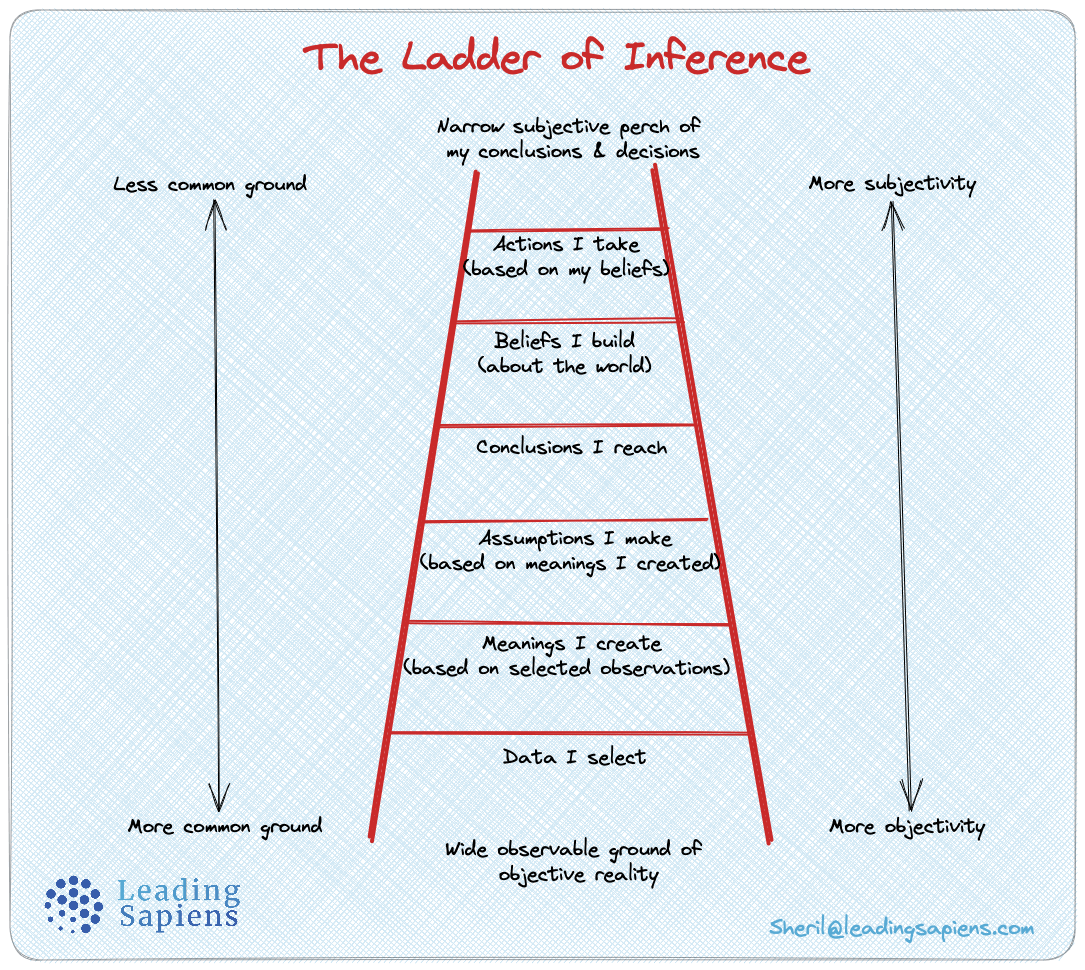

When we interact with other people on the basis of a particular mental model, we usually try to defend that model against any challenges. Our energy goes into explaining our model to others and defending it from criticism. Parrying critiques of our model gives us a deeper understanding of it, but it teaches us nothing about the models other people hold in their heads. In fact, the defensive stance helps ensure that we never learn anything about models that might oppose our own. And that keeps us from finding clues that might lead to a creative resolution should our mental model come into conflict with someone else’s mental model.

The antidote to advocacy is inquiry, which produces meaningful dialogue. When you use assertive inquiry to investigate someone else’s mental model, you find saliencies that wouldn’t have occurred to you and causal relationships you didn’t perceive. You may not want to adopt the mental model as your own, but even the least compelling model can provide clues to saliencies or causal relationships that will generate a creative resolution.

Assertive inquiry’s intent isn’t argumentative, and its method isn’t to ask leading questions (“don’t you think that . . . ?”) or discourage challenge (“wouldn’t you agree that that . . . ?”).

Assertive inquiry involves a sincere search for another’s views (“could you please help me understand how you came to believe that?”) and tries to fill in gaps of understanding (“could you clarify that point for me with an illustration or example?”). It seeks common ground between conflicting models (“how does what you are saying overlap, if at all, with what I suggested?”).

Assertive inquiry isn’t a form of challenge, but it is pointed. It explicitly seeks to explore the underpinnings of your own model and that of another person. Its aim is to learn about the salient data and causal maps baked into another person’s model, then use the insight gained to fashion a creative resolution of the conflict between that person’s model and your own.

Assertive inquiry promotes generative reasoning and causal modeling. It enables generative reasoning by breaking down conflicting models into pieces that can be recombined into something better than either of the two models that are in conflict. And assertive inquiry produces more robust causal modeling by enlisting more minds to explore and map the material and teleological links that undergird the conflicting models.

Assertive inquiry is one way to get better at the ethos and pathos in the Aristotelian triad of ethos, pathos, and logos.

For a more in-depth look at what balancing advocacy and inquiry means, check out this piece:

Assertive inquiry at the org level

In his strategy treatise Playing to Win along with former P&G CEO A.G. Lafley, Martin highlights how assertive inquiry was implemented at the organizational level in what he calls "new norms for dialogue".

This indeed is a new norm because in most workplaces, and especially amongst leaders, there's too much advocacy and not enough of inquiry. Organizations are often gladiatorial battlefields with persons and groups pitching for their own positions in a winner-take-all matchup.

No wonder Martin calls inquiry as the "anti-dote" and outlines 3 key tools they used at P&G. He explains:

In any conversation, organizational or otherwise, people tend to overuse one particular rhetorical tool at the expense of all the others. People’s default mode of communication tends to be advocacy—argumentation in favor or their own conclusions and theories, statements about the truth of their own point of view. To create the kind of strategy dialogue we wanted at P&G, people had to shift from that approach to a very different one.

The kind of dialogue we wanted to foster is called assertive inquiry. Built on the work of organizational learning theorist Chris Argyris at Harvard Business School, this approach blends the explicit expression of your own thinking (advocacy) with a sincere exploration of the thinking of others (inquiry). In other words, it means clearly articulating your own ideas and sharing the data and reasoning behind them, while genuinely inquiring into the thoughts and reasoning of your peers.

To do this effectively, individuals need to embrace a particular stance about their role in a discussion. The stance we tried to instill at P&G was a reasonably straightforward but traditionally underused one: “I have a view worth hearing, but I may be missing something.” It sounds simple, but this stance has a dramatic effect on group behavior if everyone in the room holds it. Individuals try to explain their own thinking—because they do have a view worth hearing. So, they advocate as clearly as possible for their own perspective. But because they remain open to the possibility that they may be missing something, two very important things happen.

One, they advocate their view as a possibility, not as the single right answer. Two, they listen carefully and ask questions about alternative views. Why? Because, if they might be missing something, the best way to explore that possibility is to understand not what others see, but what they do not.

Contrast this to managers who come into the room with the objective of convincing others they are right. They will advocate their position in the strongest possible terms, seeking to convince others and to win the argument. They will be less inclined to listen, or they will listen with the intent of finding flaws in other arguments. Such a stance is a recipe for discord and impasse.

We wanted to open dialogue and increase understanding through a balance of advocacy and inquiry.

This approach includes three key tools:

(1) advocating your own position and then inviting responses (e.g., “This is how I see the situation, and why; to what extent do you see it differently?”);

(2) paraphrasing what you believe to be the other person’s view and inquiring as to the validity of your understanding (e.g., “It sounds to me like your argument is this; to what extent does that capture your argument accurately?”); and

(3) explaining a gap in your understanding of the other person’s views, and asking for more information (e.g., “It sounds like you think this acquisition is a bad idea. I’m not sure I understand how you got there. Could you tell me more?”).

These kinds of phrases, which blend advocacy and inquiry, can have a powerful effect on the group dynamic. While it may feel more forceful to advocate, advocacy is actually a weaker move than balancing advocacy and inquiry. Inquiry leads the other person to genuinely reflect and hear your advocacy rather than ignoring it and making their own advocacy in response.

We actively fostered this approach to communication at P&G, encouraging dialogue in the strategy review sessions, in one-on-one meetings, and all the way to the boardroom. The goal was to create a culture of inquiry that would surface productive tensions to inform smarter choices. The explicit goal was to create strategists at all levels of the organization. ...

Taking a group of individual high achievers and asking them to work together to craft strategy is no simple matter. Since strategic choice is a judgment call in which nobody can prove that a particular strategy is right or the best in advance, there is a fundamental challenge to coming to organizational decisions on strategy. Everyone selects and interprets data about the world and comes to a unique conclusion about the best course of action. Each person tends to embrace a single strategic choice as the right answer. That naturally leads to the inclination to attack the supporting logic of opposing choices, creating entrenchment and extremism, rather than collaboration and deep consideration of the ideas.

To overcome this tendency, P&G needed to create a culture of inquiry and norms of communication that allowed individuals and teams to be more rather than less productive.

Related reading

- Implementing this approach along with the ladder of inference to run more effective meetings.

Sources

- The Opposable Mind by Roger Martin

- Playing to Win by Roger Martin, AG Lafley