Would you rather be a pro or an amateur? How about choosing between sophistication and naiveté? Most of us choose to be sophisticated pros. But consider the fact that expertise comes with its own pitfalls, while deliberately staying an amateur has its counter-intuitive upsides. The trick is in balancing the tension between the two.

The beginner and the master

The word amateur in modern usage has a negative connotation of someone who's not serious — a dabbler or a dilettante. But consider that the ancients used the term in the context of love and devotion to your craft.

Too often, in the process of becoming professionals, we lose the original naiveté and curiosity that got us there. Left unchecked, it can easily become a barrier to our continued evolution and a stumbling block.

The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything.

— Steve Jobs (after being fired from Apple) [3]

In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.

— Shunryu Suzuki in Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind

The real challenge then is not just in becoming a pro, but rather maintaining the beginner’s mind in concert with increasing levels of mastery. What is characteristic of extraordinary mastery and productivity is that the true masters find new ways of engaging with their craft, and in the process both master and craft evolve together.

The deliberate amateur

Sarah Lewis calls this the “wisdom of the deliberate amateur” in her book The Rise:

An ever-onward almost is part of mastery, on the field, in the studio, and in the lab. The wisdom of the deliberate amateur is part of how we endure. Maintaining proficiency is best kept by finding ways to periodically give it up.

It is an old idea for artists, seen in the freedom that comes in a late style or the Zen concept of “beginner’s mind,” a shift in perspective that comes from trying to see things anew after gaining sufficient expertise.

“As you grow older, every book becomes a little more difficult,” author Erskine Caldwell told The Paris Review about the process of writing, not just “because you’re more critical of what you’re doing,” but because “you reach the point where you know something is wrong but you’re incapable of making it any better.”

Choreographer Twyla Tharp also used the technique. “Experience . . . is what gets you through the door. But experience also closes the door,” she said. “You tend to rely on that memory and stick with what has worked before. You don’t try anything anew.”

Without off-road exploration, we have little way of figuring it out. The amateur’s “useful wonder” is what the expert may not realize she has left behind.

The deliberate amateur deftly avoids what psychologists call the Einstellung effect, and keeps their practice fresh by straddling the tension between the ignorance of the novice and the blindness of the expert.

An amateur is unlike the novice bound by lack of experience and the expert trapped by having too much. Driven by impulse and desire, the amateur stays in the place of a “constant now,” seeing possibilities to which the expert is blind and which the apprentice may not yet discern. It can lead to playing like there’s “no birth certificate on your notes,” as Ornette Coleman once said about a trumpeter’s sound. It keeps us in the spirit of discovery.

An amateur’s adventure is an embodied feeling of being rapt, utterly absorbed. We sense it after reaching a state of exhaustion, switching tasks to something that has our interest, and feeling refueled, our endurance enhanced by authentic passion. For a moment, we are out of time.

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and writer Ludwig Börne both made the case for periodically cultivating this approach. ...

Börne argued for “the art of making oneself ignorant” in his controversial 1823 essay, “How to Become an Original Writer in Three Days.” Inherited knowledge, he said, was like some “ancient manuscripts where one must scrape away the boring disputes of would-be Church Fathers and the ranting of inflamed monks to catch a glimpse of the Roman classic lying beneath.”

Schopenhauer developed Börne’s idea when he called for an “intellectual Sabbath” from constantly being on “the playground of others’ thoughts.” Worried that “his age would ‘read itself stupid,’ ” and no longer be able to generate novel ideas, he outlined his logic with an analogy about riding versus walking: If a person only rides and never walks, she will soon lose the ability to walk herself anywhere. Follow someone else’s route too often and soon you lose the ability to map out your own.

Why do most of us don't go down this alternate path? For one, we would rather not look foolish. And two, because the uncertainty of stepping into the unknown can be painfully uncomfortable, which most of us have long forgotten how to navigate.

Lewis cites the example of Noble Laureate physicist Sir Andre Konstantin Geim:

“You always can be considered as a fool,” Geim said, “inventing the wheel, investing your time into something, which might turn out like a blip.” It can turn a walk into a wander.

Geim described how hard it was to switch subjects, moving from semiconductor physics to superconductivity. “I went to those conferences as a beginner with having a couple of already prestigious papers, being an associate professor.

People looked at me [and said], ‘Who is this materials postdoc? What is he doing?’ Because I came from a completely different community . . . It’s not secure. You’re moving in the unknown waters which are not only scientifically unknown but . . . psychologically.”

The approach means moving forward by backpedaling, running to get up to speed, leaping, then scanning the field midair to find out if you’re wasting your time.

How do you deal with the uncertainty and discomfort? The paradoxical combination of courage coupled with playfulness is one answer:

This agility takes an inordinate amount of “courage,” Geim said. “I suppose,” he said, that is where “play comes in.”

Playfulness lets us withstand enormous uncertainty: The deliberate amateur knows no other way.

Beginner's mind and your career

So how does this apply to the rest of us mortals who are not zen masters or Nobel laureates?

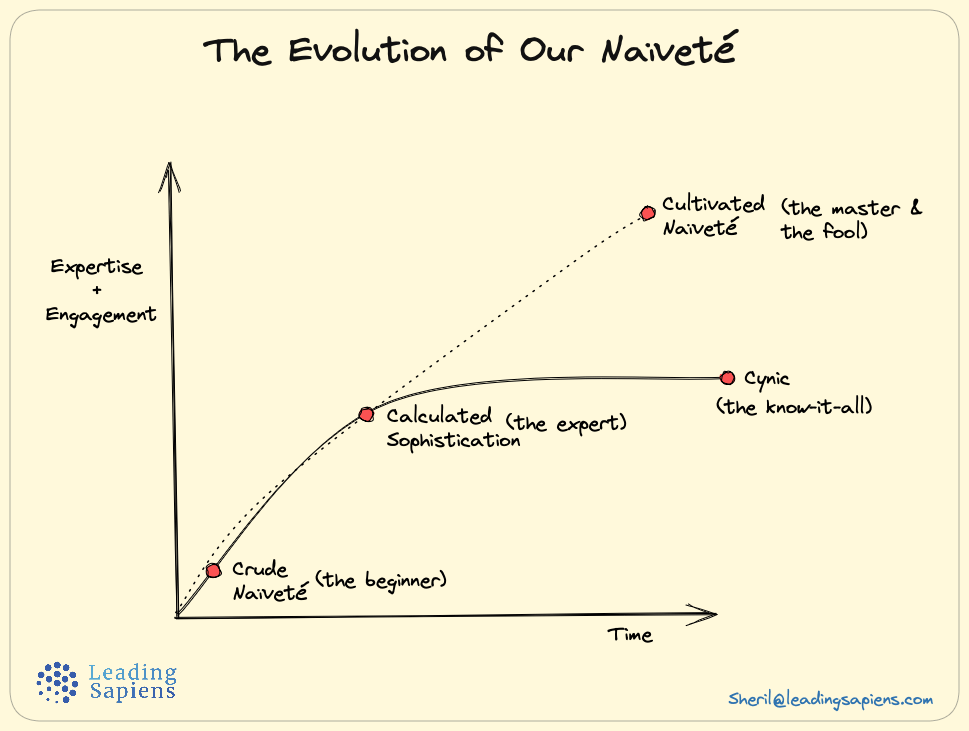

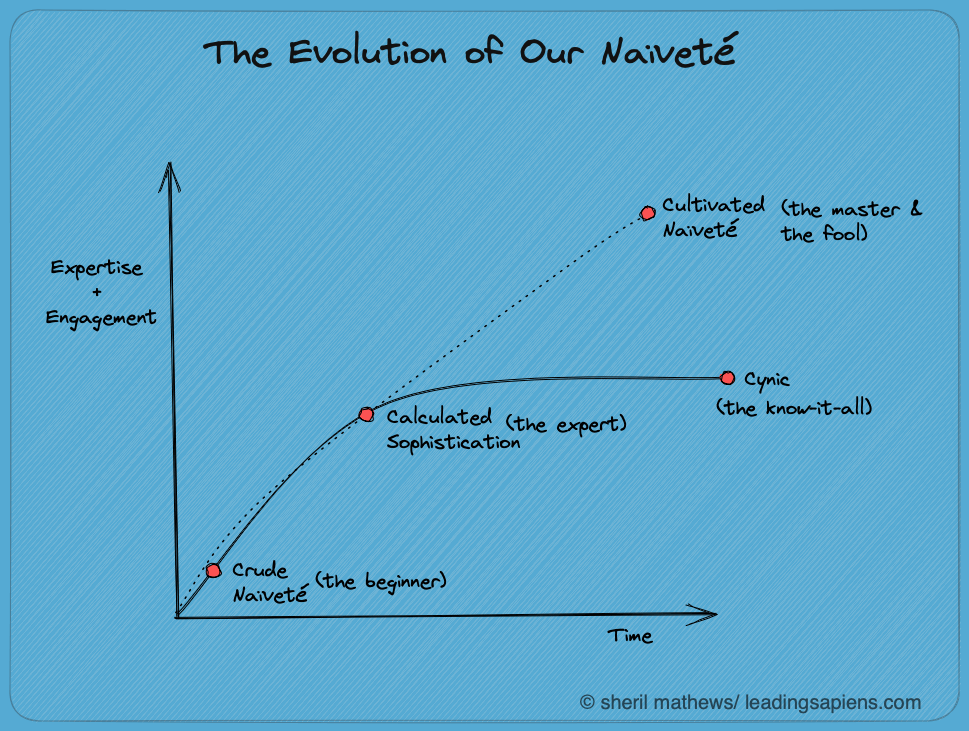

It's a helpful framework especially in mid-career — a tricky terrain to navigate because it's easy for expertise to turn into cynicism and stagnation. This is especially true when operating in larger organizations, where silos and specialization are the norm.

It's not "scientific" but the below sketch captures some of the dynamics:

In many ways, corporate existence is designed to maximize the exploit mode, often at the cost of the explore mode. This makes us more tuned to efficiency, but that comes at the cost of insight and creativity. It's how people lose the motivation and drive that carried them through their early years.

Thus, staying in touch with our original naiveté is an effective antidote against mid career doldrums that derail many.

Related reading

- I took a deep dive into the role of naiveté in leadership and how we over-index for sophistication:

- Many of us will have a better chance of becoming pros if we actually knew what it takes. We tend to be intimately familiar with desired outcomes but not with the mundane actions required to get there. In a sense, we are naive about the realities of becoming a pro. Keeping up with the mundanity long enough is a bigger challenge than the outcome itself:

Sources

- The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure, and the Search for Mastery by Sarah Lewis

- Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind by Shunryu Suzuki

- Beginners: The Joy and Transformative Power of Lifelong Learning by Tom Vanderbilt