Self-doubt is often seen as an impediment to effective leadership or succcess in any other arena. We have an image of effective leaders or successful folks as being supremely confident.

The reality is that self-doubt goes hand in hand with any worthwhile endeavor. So how do we go about handling it? Should we even try to eliminate it? Or can it be a positive indicator?

Doubt as a criteria

Many of us operate under the notion that we are not fully competent yet at something, and as a result either wait on the sidelines or second-guess.

We hold ourselves back from doing the very thing that we know needs done to unlock what we are capable of. We question our ability to get something done when it is beyond our perceived notions of competence and capability. Aka self-doubt.

Leaders need to be aware of this tendency both in themselves and in their teams.

This is especially true in domains of high complexity, high variation, and low definition like that of leadership. These domains are complex adaptive rather than the opposite of technical domains with proven solutions and widely agreed upon measures of competence.

A non-psychological take on self-doubt

A psychological interpretation of this inaction or doubt is a lack of courage, lack of willpower, or even worse a weak character. But there might be a simpler explanation.

Often assessments do not have clear benchmarks. Upon closer examination though, many of our notions lack grounding. Paying attention to language, and how we come to conclusions can be illuminating.

For example, if you don’t consider yourself an “ok manager” where is that assessment coming from and what is it based on? What's your baseline benchmark? What's the definition of “ok”? How do you quantify it?

We also tend to give others the benefit of doubt while not extending the same courtesy to ourselves. We find it easier to assume others as experts while being equally hard on ourselves.

Kings and philosophers shit and so do ladies.

- Michel de Montaigne in Essays

While we are intimately aware of our own shortcomings, we do not have the same vantage point on others. We do not have an insider’s look at what the so-called experts are going through themselves. That’s just how our human OS is designed.

Everyone is figuring it out

In the concluding chapter of Four Thousand Weeks, Oliver Burkeman asks a powerful question that highlights this basic oversight on our part when assessing our readiness and competence to do something when compared with other presumed experts. [1]

In which areas of life are you still holding back until you feel like you know what you’re doing?

It’s easy to spend years treating your life as a dress rehearsal on the rationale that what you’re doing, for the time being, is acquiring the skills and experience that will permit you to assume authoritative control of things later on.

But I sometimes think of my journey through adulthood to date as one of incrementally discovering the truth that there is no institution, no walk of life, in which everyone isn’t just winging it, all the time.

Growing up, I assumed that the newspaper on the breakfast table must be assembled by people who truly knew what they were doing; then I got a job at a newspaper. Unconsciously, I transferred my assumptions of competence elsewhere, including to people who worked in government. But then I got to know a few people who did—and who would admit, after a couple of drinks, that their jobs involved staggering from crisis to crisis, inventing plausible-sounding policies in the backs of cars en route to the press conferences at which those policies had to be announced.

Even then, I found myself assuming that this might all be explained as a manifestation of the perverse pride that British people sometimes take in being shamblingly mediocre. Then I moved to America—where, it turns out, everyone is winging it, too. Political developments in the years since have only made it clearer that the people “in charge” have no more command over world events than the rest of us do.

It’s alarming to face the prospect that you might never truly feel as though you know what you’re doing, in work, marriage, parenting, or anything else.

But it’s liberating, too, because it removes a central reason for feeling self-conscious or inhibited about your performance in those domains in the present moment: if the feeling of total authority is never going to arrive, you might as well not wait any longer to give such activities your all—to put bold plans into practice, to stop erring on the side of caution.

It is even more liberating to reflect that everyone else is in the same boat, whether they’re aware of it or not.

– Oliver Burkeman in Four Thousand Weeks

The idea is not to overnight call yourself an expert or attempt impossible things, but rather to second-guess our second-guessing. To interrupt ourselves when we go down the rabbit hole of doubt, and take action in spite of, rather than be paralyzed by, self-doubt.

While we might not explicitly ask for permission, sometimes there is an implicit expectation of permission from anything or anyone other than ourselves. It could be a course, an MBA program, or our managers.

Some of us wait for permission to assume leadership particularly in undefined and emerging situations.

Often unacknowledged and unrecognized, we look for a sense of certainty from work and managers in order to counter the uncertainty that naturally coexists with complexity. This becomes an impediment because we are looking for something that does not exist and in the wrong places.

None of us has a real understanding of where we are heading. I don’t. I have a sense about it . . . but decisions don’t wait. Investment decisions or personnel decisions and prioritization don’t wait for the picture to be clarified. You have to make them when you have to make them. So you take your shots and clean up the bad ones later.

- Andy Grove, former Intel CEO

The reality is that executives, and CEOs are figuring it out themselves as much as the rest of us. Reality is way too complex for any one person to have figured it all out, even though they might claim to have done so or it looks that way from the outside. This is both troubling and liberating.

If our whole strategy was to rely on experts and their assessments, this can be disorienting. It puts the onus of action on us, and to take the action right now instead of waiting for permission or waiting for the right time when we feel ready and competent.

But it's liberating because we are now on an even playing field with everyone else.

Action creates feedback and clarity

While Burkeman mentions it as winging it, there is a deeper truth in what he’s talking about. In more complex arenas that don't have direct correlation between cause and effect, action creates feedback that we can then act upon and improvise further. [2]

Every small action that we take, reveals properties of the system that was previously invisible or inaccessible. Without action, everything is a conjecture, a best guess. When we take action it creates clarity and helps further fine-tune our approach.

And action does not have to be coupled with self-doubt even though some folks might have you believe otherwise. Action can be taken regardless of the presence or absence of doubt.

H. L. Mencken wrote, “For every complex problem, there is a simple solution that doesn’t work.”

Working on our insides—using subtle or sophisticated techniques to change our beliefs, fix our feelings, feel confident, banish self-doubt, quiet the mind, think positive thoughts, or attract whatever we desire—represents “simple solutions” that don’t work, unless we also act.

Visualizing pineapples will not turn me into a citrus fruit.

- Dan Millman in Living on Purpose

While the term winging it might have a negative connotation, it does not have to be. We need to be as prepared as we possibly can, but not at the expense of taking action when it is required. Even the most prepared ones have to spontaneously respond to what shows up.

Treating an emerging situation with pre-conceived notions only blinds us to the details and rich texture of reality that actually might hold the answers to what we are looking for. Winging it can also be seen as being fully present, fully available, and fully responsive.

This resistance to the idea of winging it arises from our cultural bent towards looking for causality and trying to make everything formulaic. The underlying assumption is that some people have it figured out while others haven’t.

But in ambiguous and complex situations that most of us face on a daily basis, there are no pre-proven formulas. What does come in the way, is trying to look for a formula where there might not be any.

Dunning-Kruger Effect and Impostor Syndrome

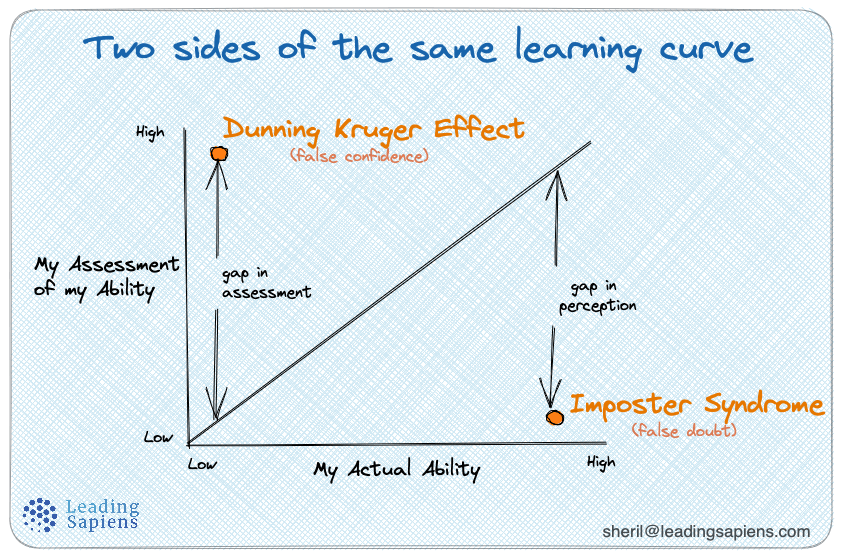

When we push the limits of our performance there are two insidious effects to be aware of: the Dunning-Kruger effect and Impostor Syndrome. They are opposites on a spectrum of our actual ability vs our self-assessment of it. [3]

Dunning-Kruger effect is when your actual ability is low but your self-assessment about it is high. In simpler terms, ignorance is bliss. You don’t know what you don’t know. Beginners often rate themselves higher on a given skill compared to experts.

Impostor syndrome is the other end of this spectrum where your ability is actually pretty high but your assessment of it is pretty low. Or you don’t give enough weight and credence to what you have already achieved.

What makes this really insidious is that the more conscientious and competent we are, more likely we are aware of our weaknesses which makes us more prone to underrating our true ability.

The flip side is that ignorance and hubris leads to false confidence.

A fragile version of self-belief

Doubt and conflict come with the territory when trying anything worthwhile. The sooner we accept it, the faster we can move on to doing what matters.

Our belief that self-belief has to be absolute means that we inevitably see any self-doubt as a sign of weakness to be expunged. In other words, self-doubt undermines will only because we have not learned to live with doubt.

- Julian Baggini, Antonia Macaro in The Shrink and The Sage

In some circles, the very existence of self-doubt is a big no-no. But this can easily lead to a fragile self-belief where you are constantly hunting to eliminate self-doubt and using it as a negative indicator.

Rollo May called this the “conflict-free adjustment” that too often all of us fall for. We want the outcomes but without the necessary turmoil that comes along for good measure.

When we see the intimate feelings and inner experiences of an eminent artist like Giacometti, we smile at the absurd talk in some psychotherapeutic circles of “adjusting” people, making people “happy,” or training out of them by simple behavior modification techniques all pain and grief and conflict and anxiety.

How hard for humankind to absorb the deeper meaning of the myth of Sisyphus!—to see that “success” and “applause” are the bitch goddesses we always secretly knew they were.

To see that the purpose of human existence in a man like Giacometti has nothing whatever to do with reassurance or conflict-free adjustment.

He knew there was no other alternative for him. This challenge gave his life meaning.

- Rollo May in Courage to Create [6]

Being comfortable with the existence of self-doubt can help build a more resilient version of self-belief that is more robust to the vagaries of life and work.

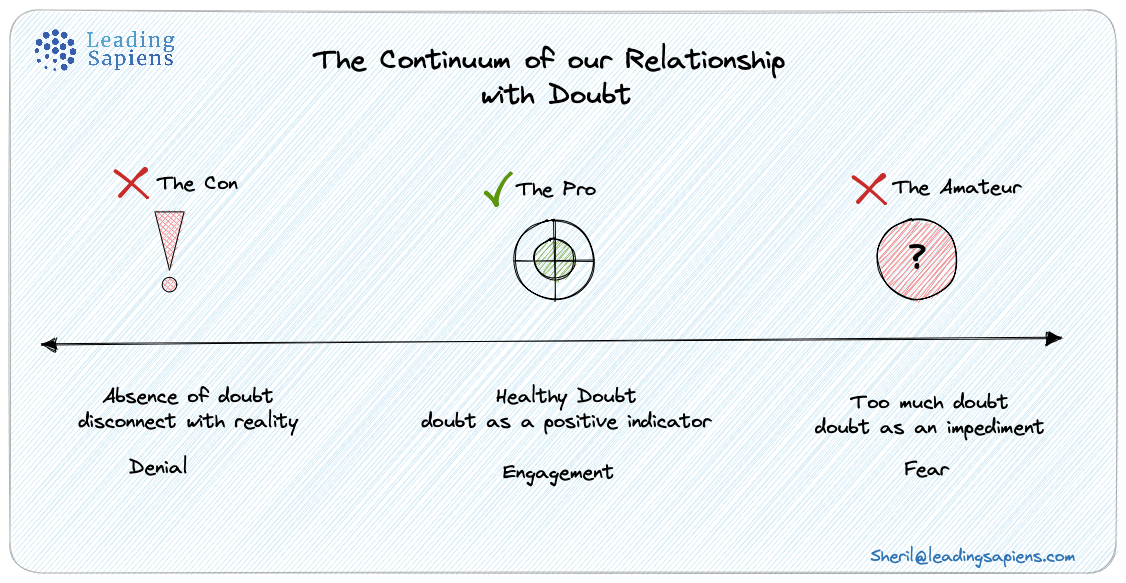

Absence of self-doubt as the wrong criteria

Another key takeaway from Burkeman’s piece is that there will not be a redemption day when we finally deem ourselves as competent and be completely free of self-doubt or reservations about our abilities.

The absence of doubt as some sort of an objective criteria and actively trying to eliminate it is counter productive and not consistent with the human experience.

Commitment and doubt can co-exist as Rollo May put it so eloquently:

Commitment is healthiest when it is not without doubt, but in spite of doubt. To believe fully and at the same moment to have doubts is not at all a contradiction: it presupposes a greater respect for truth, an awareness that truth always goes beyond anything that can be said or done at any given moment.

To every thesis there is an antithesis, and to this there is a synthesis.

- Rollo May in The Courage to Create [6]

Self-doubt comes with the territory anytime we are venturing out, trying something new, or pushing our limits. An absence of self-doubt might not be a good measure to evaluate our competence or ability to do something.

Overcoming self doubt is perhaps the wrong endeavor.

Self-doubt as a positive indicator

Inaction from self-doubt is what Steven Pressfield calls resistance. Rather than trying to eliminate it, Pressfield asks us to use this resistance as a compass to drive our actions. [4]

When it comes to doing things that push us beyond our current abilities, the more resistance we have about doing something, that’s the very thing that needs to be done in order to access our next level of complexity and performance. Self-doubt in this sense is thus a positive.

Self-doubt can be an ally. This is because it serves as an indicator of aspiration. It reflects love, love of something we dream of doing, and desire, desire to do it. If you find yourself asking yourself (and your friends), “Am I really a writer? Am I really an artist?” chances are you are.

– Steven Pressfield in War of Art

Pressfield is onto something here. If something is not in fact causing self-doubt, it’s probably too easy for us and well within our current capacity. Grappling with self-doubt rather than running away from it, is the equivalent of developing the muscles of our mind to train ourselves on doing what’s most needed for our development.

He captures both the notions of impostor syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger effect in this one powerful line:

The counterfeit innovator is wildly self-confident. The real one is scared to death.

– Steven Pressfield in War of Art [4]

The same goes for leadership and stepping into what we are actually capable of. The truly capable ones have enough self-awareness to realize their shortcomings, but they accept it as conditions of the game and take action in spite of it.

The positive side of impostor syndrome

One manifestation of self-doubt that gets a lot of press is impostor syndrome. It's often positioned as something to be ignored or eliminated so you can operate with total confidence. You will typically find this in run of the mill self-help genres.

But we don’t have to try to work it away or ignore it. As is often the case, it is simply how the human OS is designed, and it’s easier if we work with it rather than against it.

In Think Again, Adam Grant highlights the positive aspects of impostor syndrome. [5]

The first upside of feeling like an impostor is that it can motivate us to work harder. …[I]t gives us the drive to keep running to the end so that we can earn our place among the finalists.

In some of my own research across call centers, military and government teams, and nonprofits, I’ve found that confidence can make us complacent.

If we never worry about letting other people down, we’re more likely to actually do so. When we feel like impostors, we think we have something to prove. Impostors may be the last to jump in, but they may also be the last to bail out.

Second, impostor thoughts can motivate us to work smarter.[…]Remember that total beginners don’t fall victim to the Dunning-Kruger effect. Feeling like an impostor puts us in a beginner’s mindset, leading us to question assumptions that others have taken for granted.

Third, feeling like an impostor can make us better learners. Having some doubts about our knowledge and skills takes us off a pedestal, encouraging us to seek out insights from others.

As psychologist Elizabeth Krumrei Mancuso and her colleagues write, “Learning requires the humility to realize one has something to learn.”

– Adam Grant in Think Again [5]

Impostor syndrome and self-doubt are not something we need to avoid or eliminate. Rather we can work with them to improve our complexity and depth. They are definitely not a valid criteria to assess our readiness or capability.

Along the way, we have to keep reminding ourselves that everyone is on the same journey, albeit at different stages and levels of mastery.

Some questions to ponder

- What areas in work and life are you holding yourself back? Why?

- What standards are you assessing yourself against?

- Where did those standards come from?

- How would you act differently if you were already “there”?

Related Reading

- Tim Gallwey has an equation for peak performance: P = p-i where performance (P) equals potential (p) minus interference (i). Self-doubt falls on the interference side of the equation. But we can proactively focus on increasing the potential (p) side of the equation by focusing on developing our skillset. In Greatness as Mastering the Mundane, I did a deep dive into a seminal study on peak performance and how many of our notions on excellence and talent are misguided.

- Another way of looking at our relationship with doubt is what the English poet John Keats called Negative Capability. He coined the term in 1824, but it's never been more applicable to modern leadership as it is today.

- In Leadership Identity as Choices and Actions, I explore how our identities don't have to be a cause from which our actions follow, but rather effects that follow from our choices and actions.

Sources and Footnotes

- Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman. This book is a true gem and prompts deep thought in almost every paragraph. It can fundamentally reframe and shift our relationship with time and how we go about prioritizing work and life.

- Dave Snowden’s work on complexity and his Cynefin framework have been a significant influence on how I think about operating in complexity and in information-poor environments. Here’s the link to his seminal HBR article.

- Dunning-Kruger and Impostor Syndrome are well recognized and researched. I got the idea of them being opposite ends of a spectrum from Super Thinking by Gabriel Weinberg and Lauren McCann.

- War of Art by Steven Pressfield.

- Think Again by Adam Grant.

- The Courage to Create by Rollo May.

- Inner Game of Work by W. Timothy Gallwey.