Our actions, and by extension performance, stem from thinking that is based on a set of hidden mental models. How do you uncover these mental models and change them? One way is to understand and practice the concepts of single-loop and double-loop learning.

Professional sports teams use postgame films and analysis as a core part of their training regimen. What’s the equivalent for managers and other knowledge professionals? It’s mostly non-existent. Double-loop learning can help change this dynamic.

What is double-loop learning and how can you utilize it to improve performance?

Double-loop vs single-loop learning

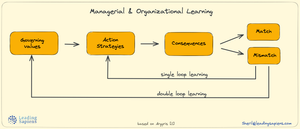

Chris Argyris of Harvard and Donald Schon of MIT were pioneers in organizational learning who developed the framework of single-loop vs double-loop learning. Argyris [1] put it this way:

Human beings produce action by activating designs stored in their heads (mind/ brain) that when activated produce the actions that are necessary to implement their intentions. Human beings also develop designs to assess the degree to which they achieve what they intended to produce. If they achieve what they intended, there is a match between intentions and actions. If they do not achieve what they intended there is a mismatch.

In order to make valid evaluations of their effectiveness, human beings must detect mismatches and correct them. At the core of acting effectively is learning. Learning also occurs if actions produce a new outcome for the first time.

Single-loop learning occurs when errors are detected and corrected without altering the governing values of the master program. Double-loop learning occurs when, in order to correct an error, it is necessary to alter the governing values of the master programs.

An example of single-loop learning would be to correct an error in an existing strategy without altering the underlying governing variables of that strategy. Double-loop learning would occur if, in order to correct and error, it is necessary to change the underlying assumptions and values that govern the actions in the strategy.

A thermostat is a single-loop learner. It is programmed to turn the heat up or down depending upon the temperature. A thermostat would be a double-loop learner if it questioned the existing program that it should measure heat.

The premise of this approach is that all actions (behavior with intentions) are produced as matches with the designs stored in our heads that we activate. These designs are developed by human beings as they strive to become skillful in whatever actions they intend.

Argyris and Schon developed and applied the framework in the context of organizational learning but it’s equally applicable to learning at the individual level.

What are the characteristic differences between single-loop and double-loop learning? How can we utilize it to become more effective? These are some of the answers we will explore. But before we jump into the details it’s useful to look at the framework that underlies them.

Bateson’s deutero-learning

Double-loop learning has its origins in cybernetics and Gregory Bateson’s levels of learning — each level requiring a completing different way of thinking and skillsets.

Zero learning is characterized by specificity of response, which—right or wrong—is not subject to correction.

Learning I is change in specificity of response by correction of errors of choice within a set of alternatives.

Learning II is change in the process of Learning I, e.g., a corrective change in the set of alternatives from which choice is made, or it is a change in how the sequence of experience is punctuated.

Learning III is change in the process of Learning II, e.g., a corrective change in the system of sets of alternatives from which choice is made.

Learning IV would be change in Learning III, but probably does not occur in any adult living organism on this earth.

— Gregory Bateson in Steps to an Ecology of Mind

Bateson coined the term deutero learning to capture the nesting effect of the levels. He was quick to point out that while Leaning III is possible, it’s no easy task and outright rules out the possibility of Learning IV in human beings:

Learning III is likely to be difficult and rare even in human beings. Expectably, it will also be difficult for scientists, who are only human, to imagine or describe this process. But it is claimed that something of the sort does from time to time occur in psychotherapy, religious conversion, and in other sequences in which there is profound reorganization of character.

Single-loop and double-loop learning essentially span the first three levels of Bateson’s learning hierarchy. Although Argyris and Schon didn’t directly address Learning III, there are others who developed the next level of Triple Loop Learning.

In more layman’s terms the three levels differ as follows:

- Level 0 - simple stimulus and response

- Level I/Single-loop: skills, techniques, methods, tips, simple set of alternatives, error correction within those alternatives

- Level II/Double-loop: changing the set of alternatives, learning how to learn, challenging assumptions of level I, altering mental models, changing thinking and ensuing actions

- Level III/Triple-loop: changing the system of alternatives itself, altering how you are, who you are being, your stance and the very context of your existence (relatively rare)

Most of us operate at level I and sometimes in level II. Rarely do we operate at level III which also tends to be a lifetime process. Bear in mind that one level is not necessarily better than other. They are nested, and their utility depends on the situion and your goals.

Single-loop learning

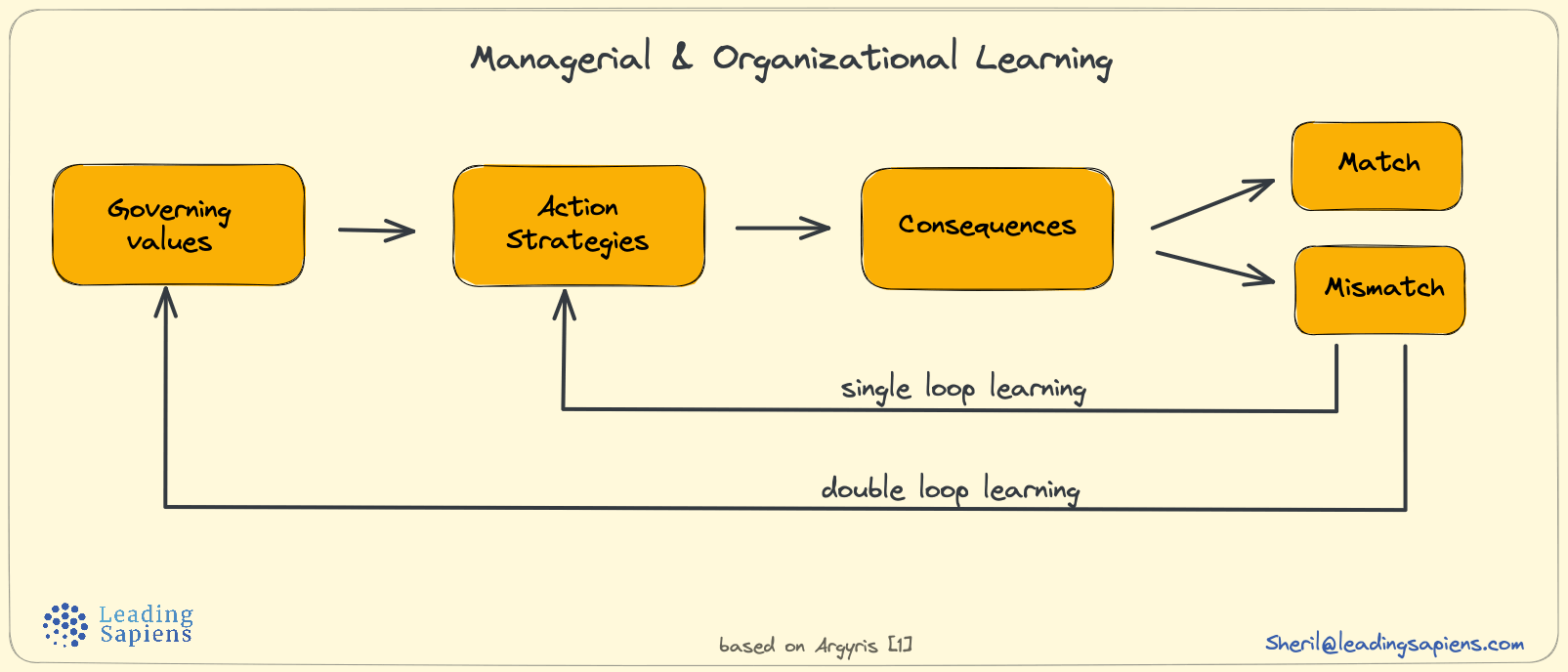

Consider this very simple model of performance — results, outcomes and consequences follow from our actions.

Our default approach of problem solving tends to delve directly on actions or the lack thereof. When we don’t get the desired results the primary mode of operation tends to focus on this first order of thinking — examining outcomes and trying to change the actions that lead to the results. And this works fine most of the time.

The primary orientation is that of “Am I getting results? If not, what am I doing incorrectly? What actions do I need to change, do more of, or less of?"

It’s characterized by typical learning of skills, refining abilities, knowledge acquisition, and acquiring new competencies but within the same realm of understanding.

Learning loops

Single loop learning can be found in versions of learning loops from other disciplines.

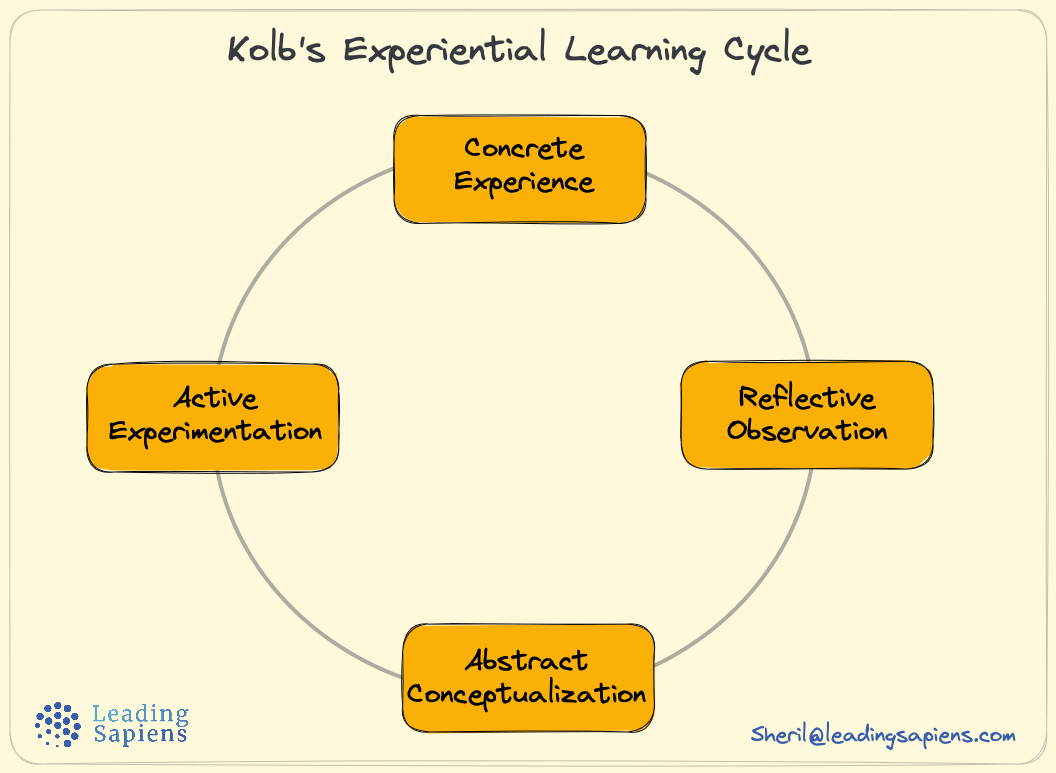

David Kolb’s experiential learning cycle:

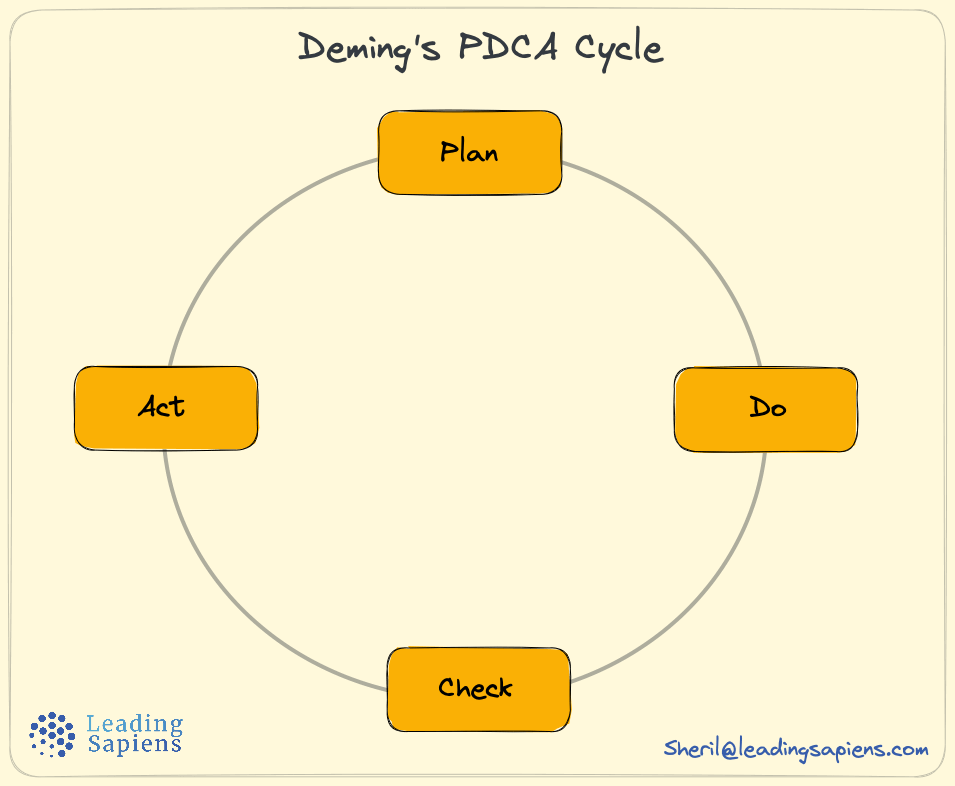

W Edward Deming’s PDCA learning loop:

There's nothing wrong with single-loop learning and works well most of the time. That's our standard mode of operating. The trouble starts when things don’t go per plan.

The problem with single-loop learning

Single-loop learning is optimal in situations where we are well trained, the solutions are known, and where there are benchmarked best practices. It's not inferior but not necessarily optimal in all situations.

Single loop learning can easily become a liability when results are not forthcoming or when operating in complex situations. How?

- It tends to be myopic by focusing exclusively on inputs and results without trying to figure out what actually produced those inputs. This creates blindspots where we don’t examine the value systems, both rational and emotional, that led us to taking a particular set of actions.

- When we fail, we blame it on execution and redouble efforts without questioning the problem itself. Focus is on more of the same actions, or doing different actions but within the same definitions and assumptions.

- Because assumptions go unexamined, good outcomes often hide bad processes until things go wrong.

- When done in response to fixing more complex problems, the gains are not sustained. The tendency is to fallback to previous levels of performance.

- Single-loop learning can block us from looking for alternatives. This is when problems start appearing “unsolvable”.

- Too much focus on single loop can hide underlying assumptions effectively making us skillfully incompetent — skilled at the what we are doing but without producing the desired results.

- Change efforts tend to be focused on the content level rather than context, which limits available set of actions.

- Focus tends to be on problem-solving rather than problem-identifying or problem-setting — optimizing right solutions for the wrong problems.

When faced with intractable problems, we try harder never actually questioning why we are doing it to begin with. We operate within the confines of a predefined problem and going around the circle never really improving or getting different results. We are on the road to nowhere. This is where double-loop learning comes in.

Single-loop learning remains within the accepted routines. Double-loop learning requires that new routines be created that were based on a different conception of the universe.

— Chris Argyris

Double-loop learning

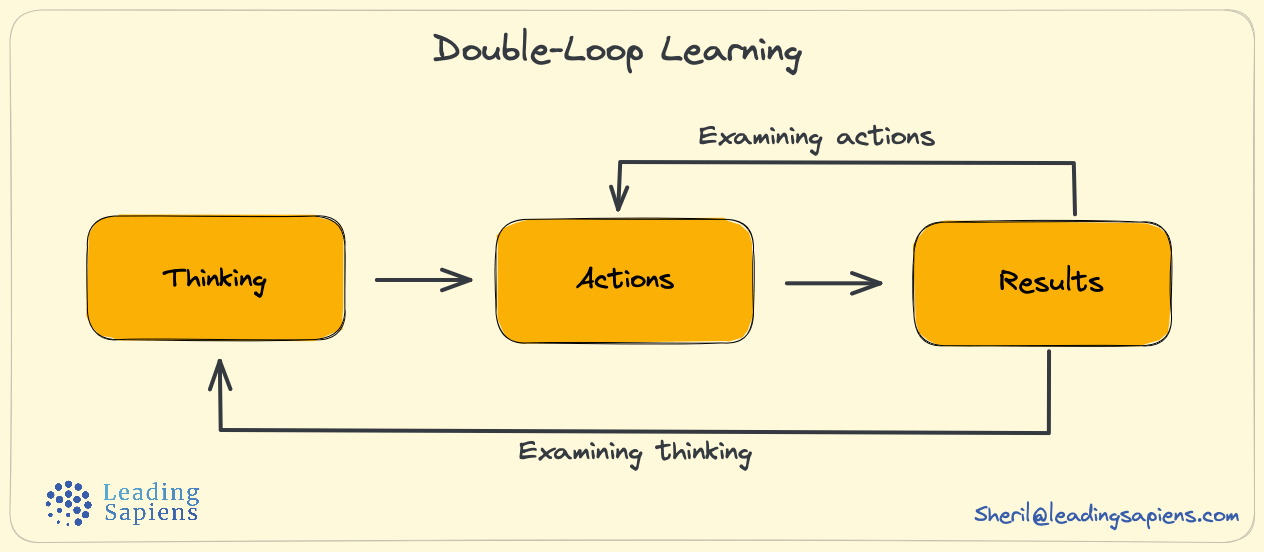

In double-loop learning, you examine and test the assumptions, thinking and mental models behind your actions. It’s what Ron Heifetz calls “going to the balcony” and watching the dance floor from a different vantage point, except in this case you are watching yourself — you are becoming a better observer of yourself. This is akin to the five why process applied to your actions and thinking.

Instead of just focusing on outcomes and actions, you loop back to the thinking that produced those actions and outcomes, reframing and redesigning the problem to uncover previously unexplored actions.

The goal is to understand context, and how you think and frame situations that influences results. This kind of evaluation is essential in order to evolve and develop your own complexity and the essential skill of metacognition.

What characterizes double-loop learning?

- A keen eye for mismatches between intent and results, and for causal links between thinking, actions, and outcomes.

- Surfacing and examining fundamental underlying assumptions and beliefs, and challenging them if they are helpful in producing desired results. The intent is to identify the reasoning that produced your actions and the elements that form your context.

- Identifying and testing your mental models requires higher levels of deliberate effort and mental awareness. This can often be uncomfortable as it requires questioning long-standing notions.

- It forces you to expand on existing capabilities or create completely new ones.

- You are thinking at the systems level and questioning the overall goal itself by examining and changing your frames of reference.

- Instead of passively playing by the rules of the game, you are not only examining and modifying the rules, but also checking if the game is worth playing. When needed, you change the game itself.

Double-loop learning has the additional dimension of being reflection driven in addition to being experiential. We are usually good at experience driven learning but reflection based learning often goes underutilized or even ignored. Latest research in neuroscience shows that these two modalities create very different kinds of neural changes. [5]

Triple-loop learning

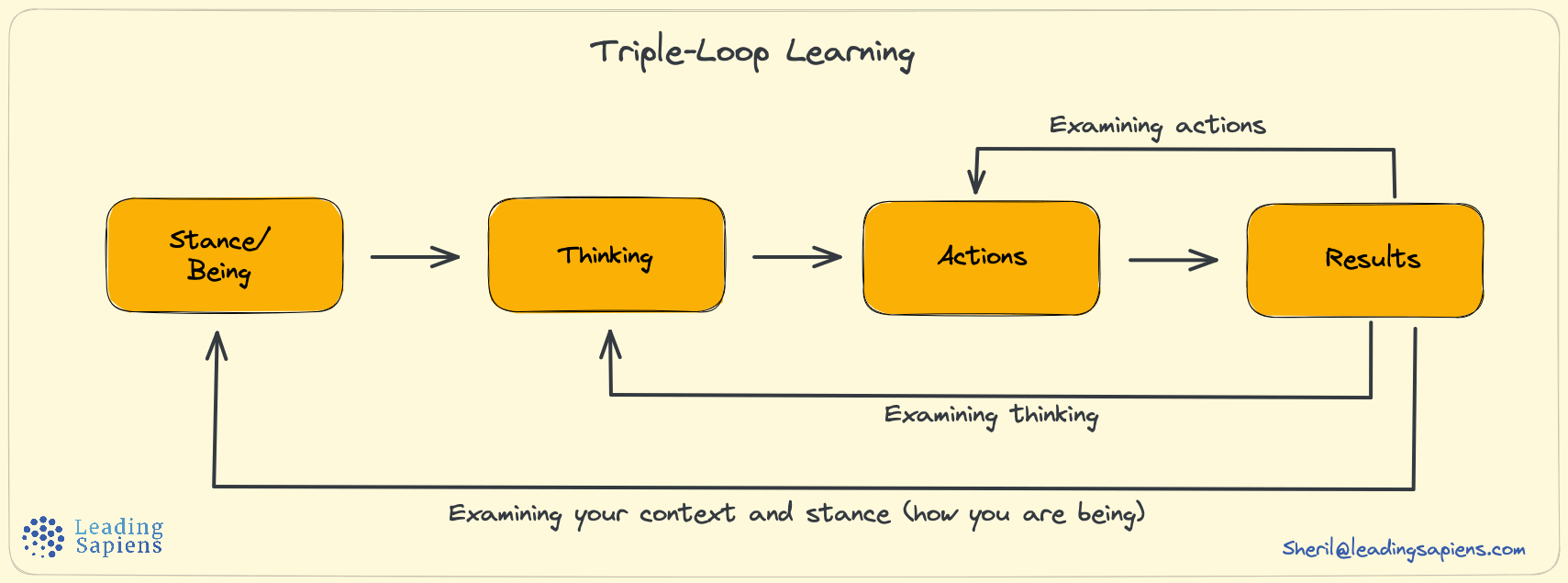

Although Argyris and Schon haven’t directly mentioned it in their work, some practitioners have written about triple loop learning where your “stance” and the way you are being, drives your thinking. [4]

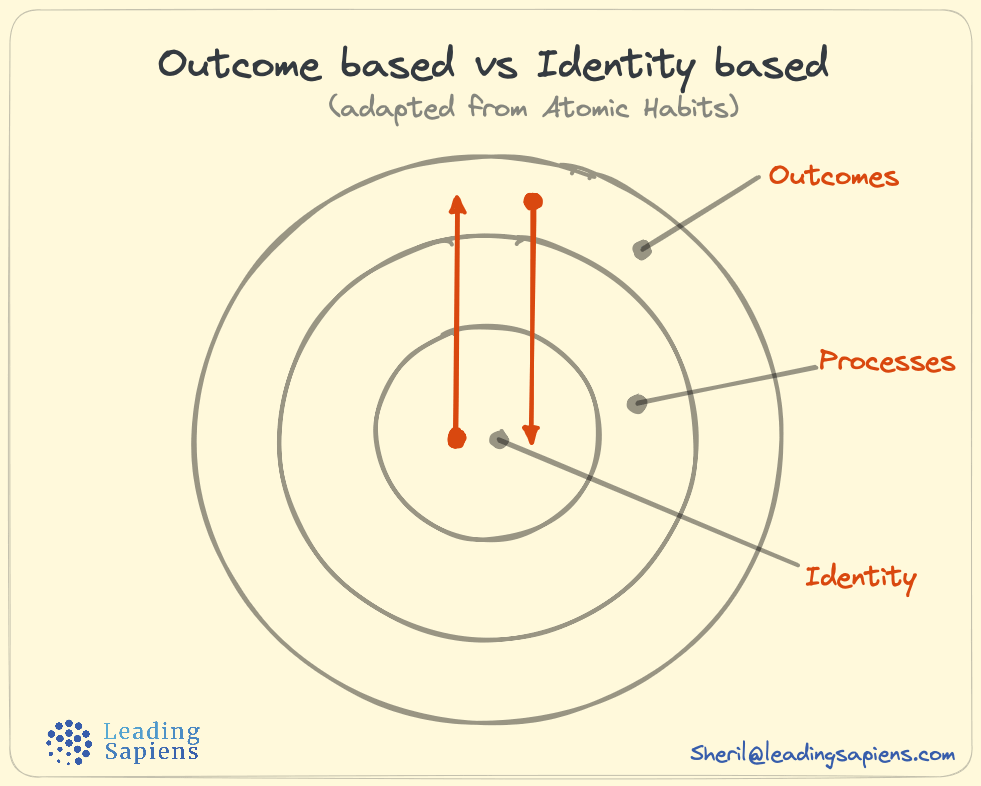

You can see hints of double-loop and triple-loop learning in James Clear's notion of identity-based habits:

Clear puts it this way in Atomic Habits:

Outcomes are about what you get. Processes are about what you do. Identity is about what you believe. When it comes to building habits that last—when it comes to building a system of 1 percent improvements—the problem is not that one level is “better” or “worse” than another. All levels of change are useful in their own way. The problem is the direction of change.

Many people begin the process of changing their habits by focusing on what they want to achieve. This leads us to outcome-based habits. The alternative is to build identity-based habits. With this approach, we start by focusing on who we wish to become.

Example of double-loop learning

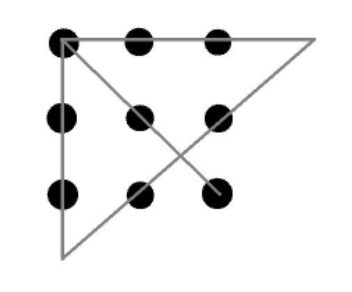

A great example of double-loop learning by examining assumptions is the nine dot puzzle — connect all the dots using only four lines and without lifting the pen.

If new to this, try solving it before going further. Most folks struggle in their initial attempts. And the primary reason we struggle? — Examining the dots themselves but forgetting about our “assumptions behind the dots”.

The mistaken assumption here being the imaginary box formed by the dots which restricts options. This is never stated but often gets assumed given our tendency to impose order on chaos. The moment you remove the imaginary box, other solutions start becoming apparent. (solution in notes at bottom)

Double-loop learning and leadership performance

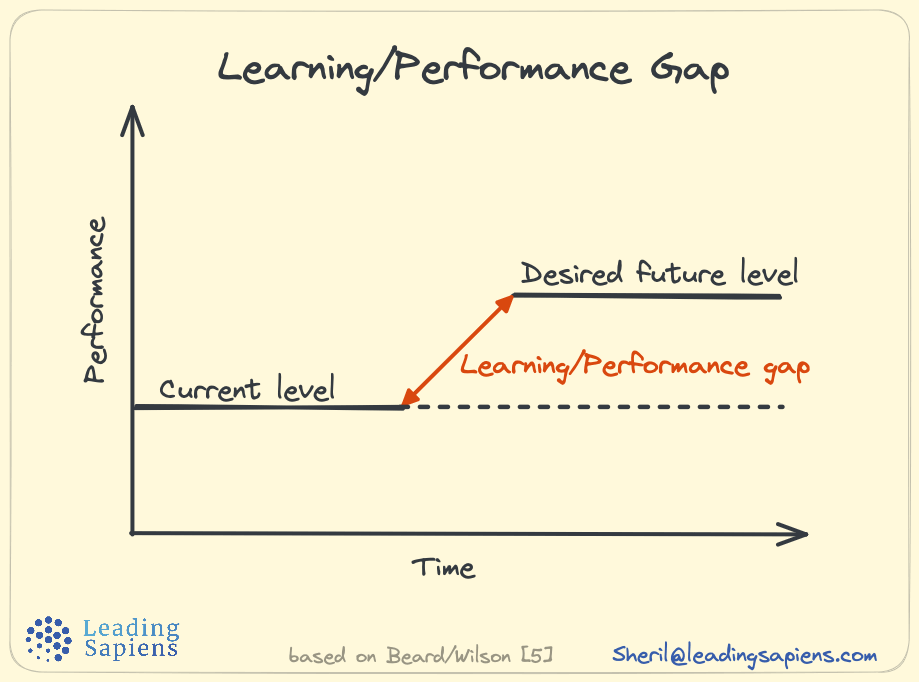

Consider where you are today and where you want to be. Let’s call this the performance gap.

Bridging this gap requires a step change in capacity which is an order of magnitude rather than simply acquiring new skills or competencies. Second order change can be thought of as vertical development as opposed to lateral where the focus is on incremental improvement in skills and competencies. Thus, a jump in performance requires a corresponding jump in capacity — where the problem looks fundamentally different to you.

How do you go about engineering this kind of step change to improve performance in a domain like leadership?

One answer is getting better at learning to learn and improving at metacognitive skills — thinking about your thinking. Double-loop learning is the equivalent of postgame film analysis for leaders that utilizes the mechanism of reflection for better performance.

What to think about often is obvious. What is not common is knowing how to think — Double-loop and triple-loop learning essentially show us how to go about developing this key skill.

Consider the following demands on leaders rise as they rise through the organization:

- You can’t predict or anticipate everything. So you better be prepared, in other words develop your capacity to handle the unexpected.

- An inability to adapt and learn has stalled one too many careers. Higher levels in the organization also mean increasing ambiguity and complexity. Fine tuned cognitive skills become a core requirement.

- Better decision making is contingent on your ability to question your own process of coming to conclusions and being able to think though multiple positions on the same issue.

- Problem solving is not the primary skillset as you go higher. Instead problem setting and problem defining start becoming more important.

- Clear thinking leading to effective action becomes a requirement.

- Skilled reflection and clear thinking leading to effective action becomes a key aspect of performance.

- You have to be adept at acquiring new skills, the capacity to master new challenges, and avoid getting into ruts or getting redundant.

- Team performance often depends on your skills of framing and setting the context.

- Your ability to operate within constraints without decreasing your capacity for action is paramount.

Building capacity at double-loop learning is an effective way to get better at these aspects of leadership. It's a process of skilled reflection, and your effectiveness is directly tied to the ability to reflect, reframe and redesign in order to create new action sets.

A primary motive of leadership coaching is to increase the ability to regularly engage in double-loop learning on your own, not just during coaching engagements.

Double-loop learning exercise

Consider your notions about what makes someone an effective leader. Do you think of yourself as effective? Can you unearth underlying notions and assumptions about it? How are they informing your actions and your behavior towards others? For more on this, check out my article that examines implicit theories about leadership that we carry, often unknowingly.

Regularly asking the following questions helps build double-loop learning capacity:

- What kind of thinking led me to these particular actions?

- Is my focus downstream or upstream?

- What’s the stance, mindset, and orientation that’s behind my thinking?

- Is my orientation helpful or hindering?

- What are the assumptions that I am not aware of?

- To what extent is my stance helpful in producing desired outcomes? How can I go about shifting it?

- What am I assuming as givens and unchangeable?

- Who am I being? What kind of doing is it enabling?

As with any form of real learning, asking these questions and actually making adjustments is not easy. Our very sense of competence and self-confidence stems from these unexamined assumptions. To actually question them is to shake the foundations of this edifice.

But that’s the only way to get better at playing the game. It's how you surface hidden mental models in order to examine them for usefulness and change them if needed. This is obviously not an overnight process and requires months, often years of practice.

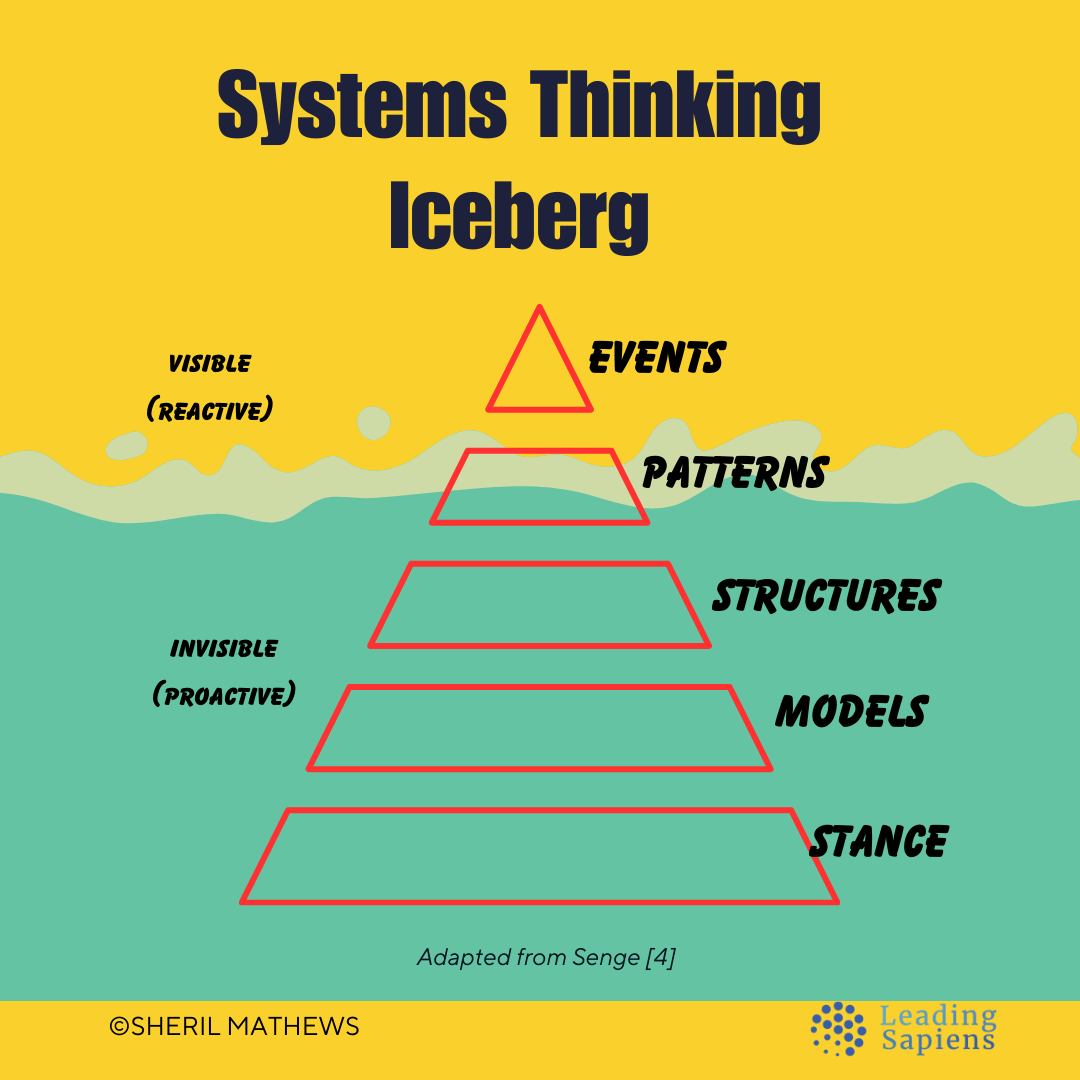

The systems thinking iceberg model highlights some parallel ideas similar to double-loop learning but taken from a systems perspective.

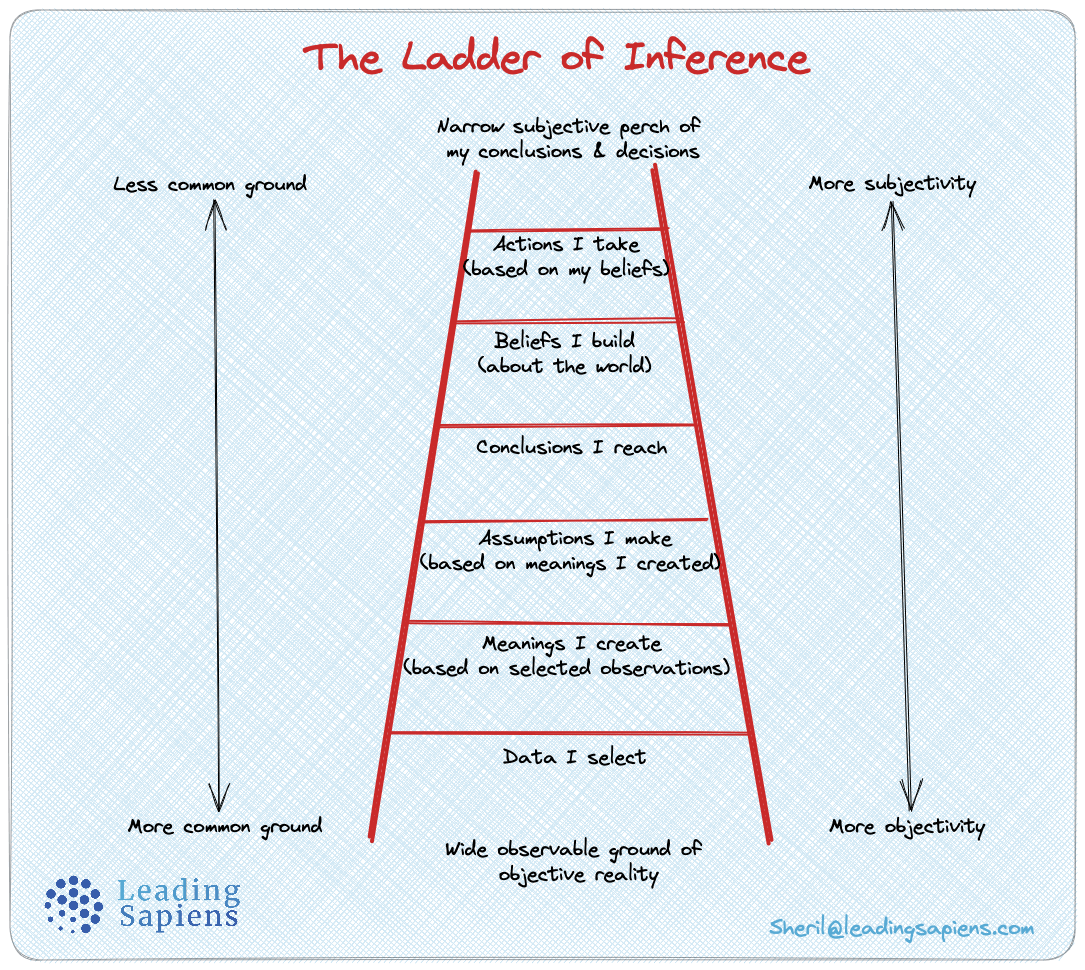

An effective tool to unearth hidden assumptions and enable double-loop learning is the ladder of inference:

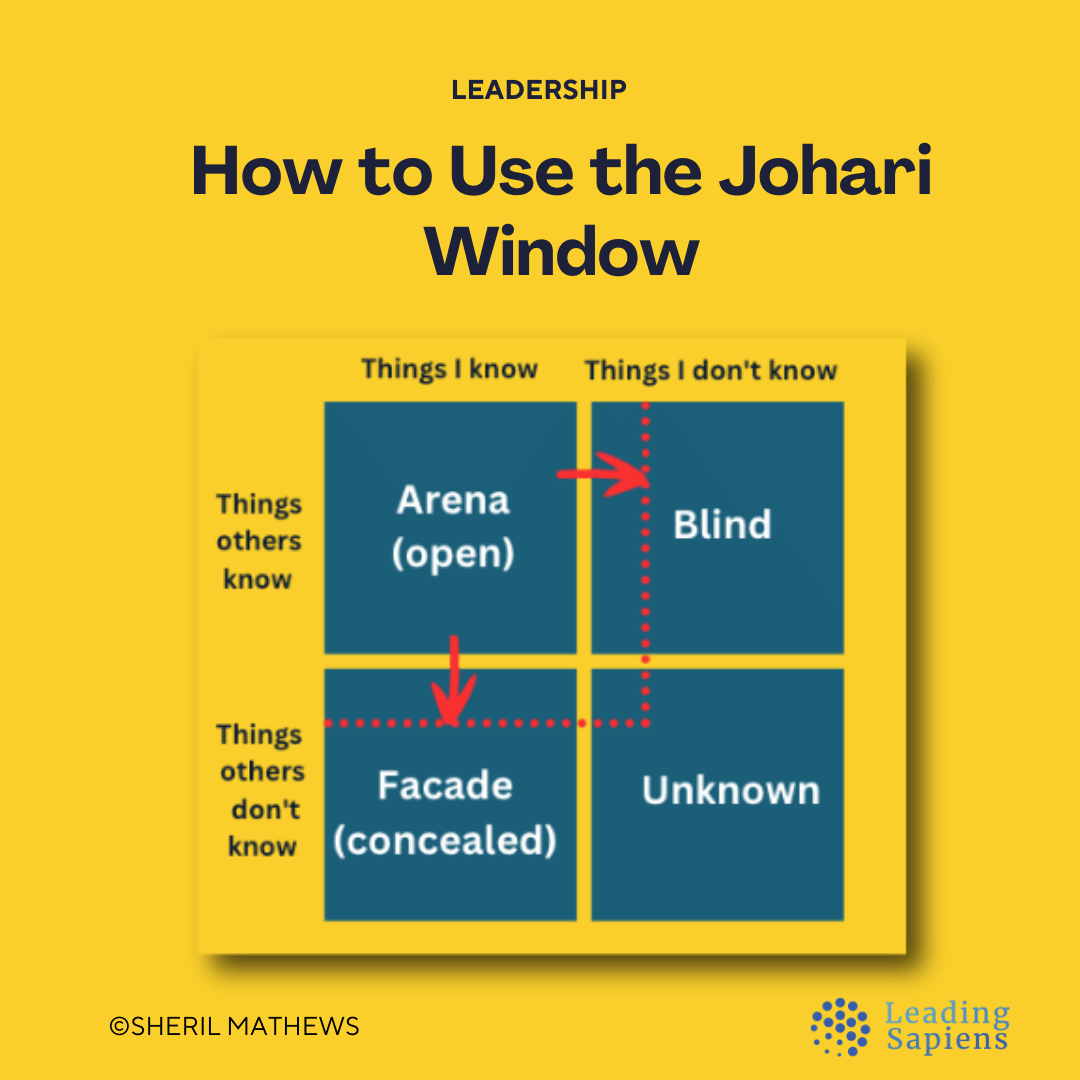

The Johari Window can be equally effective at identifying blindspots and facades that we might be using:

📚 You also get a curated spreadsheet of 100 best articles Harvard Business Review has ever published. Spans 70 years, comes complete with categories and short summaries.

Sources

- Argyris, Chris (2005). "Double-loop learning in organizations: a theory of action perspective". In Smith, Ken G.; Hitt, Michael A. (eds.). Great minds in management: the process of theory development. pp. 261–279.

- Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practice by Chris Argyris and Donald Schon

- Steps to an Ecology of Mind by Gregory Bateson

- Creating Great Choices by Roger Martin and Jennifer Riel

- Experiential Learning by Colin Beard and John Wilson

- Witherspoon, R. (2014). Double-Loop Coaching for Leadership Development. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886313510032

- Never Stop Learning by Bradley R. Staats

- Atomic Habits by James Clear

- Seibert, Kent W. and Marilyn Wood Daudelin. “The Role of Reflection in Managerial Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice.” (1999)

- Below is one solution to the nine dot puzzle. Additional ones here.