How can you run more effective meetings? One way is to study folks who are masters at running effective meetings, and get paid for it — professional facilitators.

Roger Schwarz is one of the world’s leading experts on facilitation. He has a set of what he calls ground rules for effective groups that can be easily be adapted for getting better both as a meeting organizer and participant. [1,2]

How to use these ground rules

If you’re a leader/manager, running meetings is a core skill you have to master. The ground rules will:

- Guide with behavior that’ll help to run meetings more effectively.

- Help diagnose ineffective group behaviors so you can intervene.

- Serve as a teaching tool to develop effective group norms and expectations.

As a meeting participant, these ground rules give you multiple ways to participate and add value, instead of simply being a passive bystander.

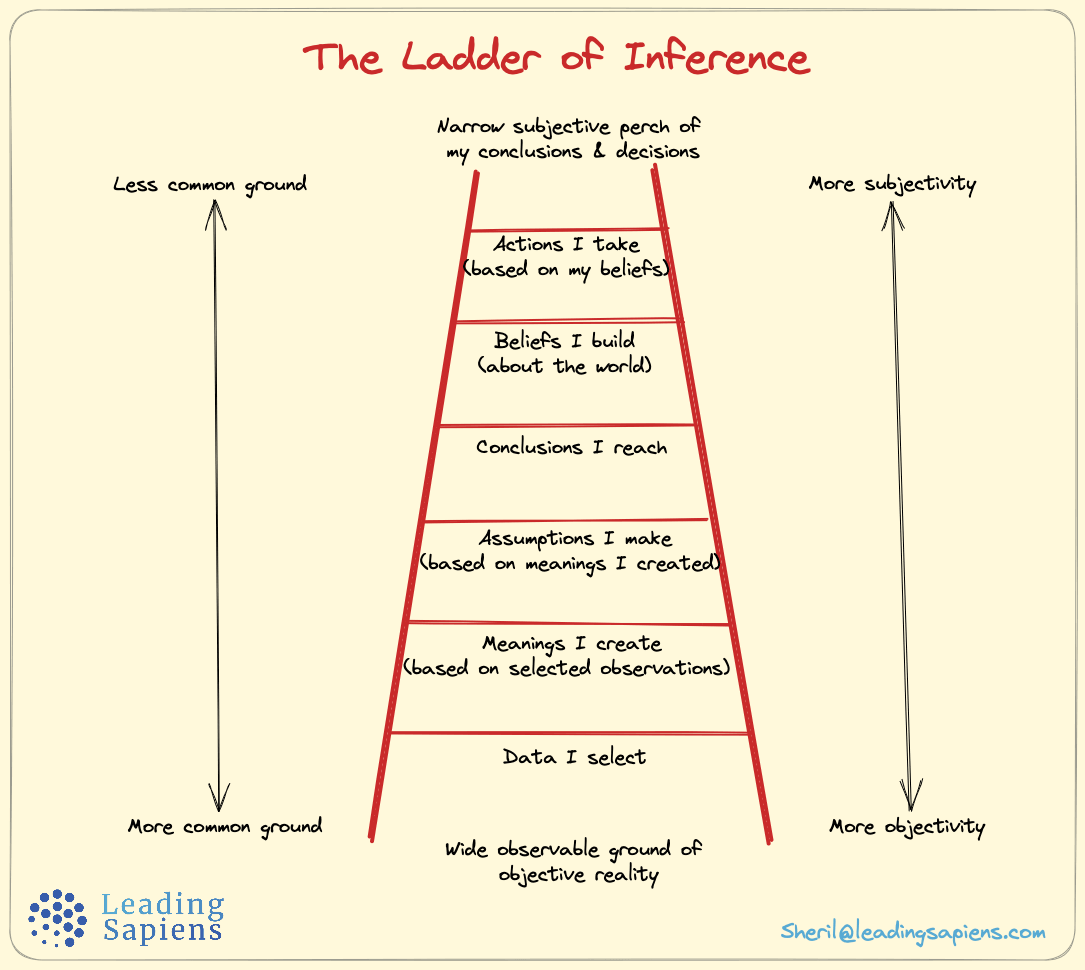

Much of the terminology used in the ground rules builds on the basics of The Ladder of Inference. Check out my article for more details:

Note: I’m using the example of meetings, but the construct is applicable to most interactions.

Let's jump in!

1. Test assumptions, inferences, and attributions

Assumptions are different from inferences, which are different from attributions. It’s important to understand the differences:

When you assume something, you take for granted that it is true without verifying it.

When you infer something, you draw a conclusion about what you do not know on the basis of things you do know.

When you attribute something, you make an inference about someone’s motives.

Assumption, inference, or attribution, the effect is the same: an untested supposition.

The problem is not that we make assumptions and inferences; we must do that to make sense out of what people are saying. The problem is that if we are unaware of the inferences we are making, our only choice is to consider them as facts rather than as hypotheses and to act on them as if they are true.

When you test assumptions and inferences, you ask others whether the meaning you are making of their behavior or of the situation is the meaning they make of it.

Examples:

- "It seems to me like you're concerned about the budget constraints. Is that what you're trying to say?"

- "I assumed you were upset when you left the meeting early. Is that correct, or was it something else?"

- "I inferred from your comments that you don't support the new policy. Am I right?"

The trick is to check the accuracy of your interpretations by asking others about their actual views, motives, and reasons for behaving a certain way. This avoids acting on incorrect assumptions, inferences, or attributions.

2. Share all relevant information

This rule means that each group member shares all the relevant information she or he has that affects how the group solves a problem or makes a decision.

Relevant information includes not only data that bear directly on the problem, decision, or other content the group is working on; it also includes information that does not support one’s preferred position and information about group members’ feelings about one another and the work they are doing.

…sharing information in a way that can be validated, which ensures that members have a common basis for making an informed choice and generating commitment.

Examples:

- "Is there information you haven't shared yet that could be relevant?"

- "Does anyone have a different interpretation that we should consider regarding this data?"

The goal is to uncover all relevant information, including opposing data, so there's a common and validated understanding when making decisions. This builds commitment through transparency.

Couple of common mistakes I’ve seen:

- Withholding information, thinking it’s obvious or that everyone’s already aware of it. Even if everyone's aware of it, they might not have given it as much thought as you have. Your perspective matters.

- Not sharing information that can potentially weaken your position. This is one of the fastest ways to build credibility that shows you’ve thought through your position and are willing to have an open discussion.

3. Use specific examples and agree on what important words mean

…a particular way of sharing relevant information that generates valid data. Using specific examples means sharing detailed relevant information, including who said what and when and where it happened.

Unlike general statements, specific examples enable others to determine independently whether the information in them is valid. By agreeing on what important words mean, you make sure that you are using words to mean the same thing that others mean.

Examples:

- "When you say the product failed in testing, what exactly happened? Let's agree on what "failure" means."

- "You stated that the team is "inexperienced." Can you provide an example showing the gap in skills you see?"

The goal is to move from vague generalizations to specific, detailed examples that everyone can understand and validate. Defining important words also creates shared meaning.

Conversely, when being given feedback, both positive and negative, ask for specific examples and making sure that their assessment is consistent with how you're interpreting it.

4. Explain your reasoning and intent

…. means explaining to others what leads you to make a comment, ask a question, or take an action. Your intent is your purpose for doing something. Your reasoning represents the logical process that you use to draw conclusions on the basis of data, values, and assumptions.

…this rule includes making your private reasoning public, so that others can see how you reached your conclusion and ask you about places where they might reason differently. A key part of explaining your reasoning is to make transparent the strategy you are using to hold the conversation.

Explaining your reasoning and making your strategy transparent are opportunities to learn where others have differing views or approaches and where you may have missed something that others see.

Examples:

- "Could you walk me through how you came to this decision?"

- "I suggested we delay the launch. My intent is to ensure we have more time for quality testing, not to hinder progress. What are your thoughts?"

The goal is to uncover the logic and motivations behind people's statements and actions explicitly, to allow for mutual understanding.

5. Focus on interests, not positions

Focusing on interests is another way of sharing relevant information. Interests are the needs, desires, and concerns that people have in regard to a given situation. Positions or solutions are how people meet their interests. In other words, people’s interests lead them to advocate a particular solution or position.

An effective way for groups to solve problems is to begin by sharing their individual interests. Once they agree to a set of interests for the group, which may or may not include all the individual interests identified, they can begin to generate solutions or positions that take that set of interests into account.

Example:

- "What concerns do you have if we go with this solution? Understanding your interests can help me find alternatives."

- "I'm open to alternatives if we can find solutions that address your interests as well as mine."

The goal is to uncover the "why" first before jumping to the "what" – interests before positions.

6. Combine advocacy and inquiry

When you combine advocacy with inquiry, you (1) explain your point of view including the interests and reasoning you used to get there, (2) ask others about their point of view, and/or (3) invite others to ask you questions about your point of view.

Combining advocacy and inquiry accomplishes several goals.

First, it can shift a series of monologues into a focused conversation. For example, in some meetings, one person speaks after the other but no one’s comments seem to directly address the previous person’s. Without an explicit invitation to inquire about or comment on the previous person’s remarks, the meeting switches focus with each person who speaks.

The second goal… is to create conditions for learning. By identifying where people’s reasoning differs, you can help a group explore what has led them to reason differently: Are they using other data, making other assumptions, or assigning different priorities to certain issues?

Examples:

- "I recommend we move forward with Option A. My interests are reducing costs and time to market. What's your take on this approach?"

- "Here’s my take on this. Given my interests and reasoning, does this make sense? What am I missing?"

- "We can't seem to agree on the right path. Can you explain your interests and logic so I can better understand your point of view?"

The goal is to integrate your stance with inquiry into others' views. This merges advocacy with genuine curiosity. Healthy conversations shuffle through the different modes, instead of being exclusively in advocacy mode that's low on inquiry. Strategist Roger Martin calls this "assertive inquiry".

7. Jointly design next steps and ways to test disagreements

In general, jointly designing next steps means (1) advocating your point of view about how you want to proceed, including your interests, relevant information, reasoning, and intent; (2) inquiring about how others may see it differently; and (3) jointly crafting a way to proceed that takes into account group members’ interests, relevant information, reasoning, and intent. Jointly designing ways to test disagreements is one specific type of next step.

Jointly designing ways to test disagreements means considering such important questions as, “How might it be that we are both correct?” and “How could we each be seeing different parts of the same problem?” A useful analogy for testing disagreements this way is two scientists who must design a joint experiment to test their competing hypotheses; the research design needs to be rigorous enough to meet the standards of both.

Examples:

- After a debate over marketing strategies, the team agrees to test both approaches on a smaller scale to gather real data on what resonates better with customers.

- The product team is split on whether to focus on incremental improvements or innovative redesigns. They decide to prototype both approaches on a few smaller projects to evaluate the outcomes.

The key is moving from positional debate to jointly designing objective tests and ways to gather more data.

8. Discuss undiscussable issues

An undiscussable issue is one that is relevant to the group, that is reducing or may reduce the group’s effectiveness, and that people believe they cannot discuss without creating defensiveness or other negative consequences. By using this ground rule together with the previous ground rules, you can discuss these issues fruitfully and reduce the level of defensiveness.

Groups often choose not to discuss undiscussables, reasoning that raising them might make someone embarrassed or defensive and that avoiding them will save face for the group’s members (and themselves). In other words, they see discussing undiscussable issues as not being compassionate.

Yet people often overlook the negative systemic—and uncompassionate—consequences they create by not raising an undiscussable issue. Examples of undiscussables are members who are not performing adequately, or are not trusting one another, or are reluctant to disagree with their manager who is also a member of the group.

Example:

“This may be a difficult issue, but I want to talk about how I think we, as your direct reports, withhold information from you because of how you react when we share bad news. I’m raising this not because I want to put anyone on the spot, but because I want us to make the best strategic decisions possible.

I’d like to share what I’ve seen that leads me to say this and test out whether others see it the same or differently.”

All human interactions have some element of the "undiscussable". At an individual level, there are aspects about us that others know but that we are unaware of. The Johari Window model is a good framework that can help with this aspect of our communication.

9. Use a decision-making rule that generates the level of commitment needed

Ground rule nine makes specific the core value of internal commitment. Its premise is that group members’ commitment to a decision is in part a function of the degree to which they make an informed free choice to support it. The more they are able to make an informed free choice, the more likely they are to be internally committed to the decision.

Practicing Ground Rule Nine means understanding that there are different types of group decision-making processes that generate different degrees of acceptance of a decision....: delegative, consensus, democratic, and consultative.

The degrees of acceptance of a decision range from resistance, to noncompliance, to compliance, to enrollment, to internal commitment. Internal commitment means that each member of the group believes in the decision, sees it as his or her own, and will do whatever is necessary to implement it effectively.

According to Schwartz’s construct, you have the following 4 kinds of decisions:

- Delegative: The leader makes the decision unilaterally and announces it. This tends to generate resistance or noncompliance from those who had no input. Usually appropriate for routine operational decisions..

- Democratic: The decision is put to a majority vote. Leads to compliance from those who voted for it, but can still leave a resistant minority. Works well for low-stakes preferences.

- Consultative: Leader gets input and recommendations but still makes the final call. Creates more buy-in than delegative, but final authority still rests with the leader. Useful when leader has expertise the group lacks.

- Consensus: The group discusses the issue extensively to understand all perspectives. The decision is shaped so that all can actively support it, though not necessarily with 100% agreement. Highest level of commitment, but most time consuming. Essential for high-stakes, mission-critical decisions.

The key is matching the decision process to the importance of commitment needed for successful implementation. More participation builds more commitment, but not always feasible.

A related idea is Jeff Bezos’ notion of disagree and commit. The article has an entire collection of Bezos' decision-making frameworks.

Sources

- Schwarz, R. M. (2002). The Skilled Facilitator.

- Schwarz, R. M., Davidson, A., Carlson, P., McKinney, S. (2011). The Skilled Facilitator Fieldbook.