The Johari Window is used to understand how we communicate based on self-knowledge and how others see us. It’s a disclosure-feedback model of awareness based on principles of feedback and learning. It can be used for increasing levels of openness, self-awareness, and self-discovery. This makes the Johari Window a particularly relevant tool for leaders and managers.

What is the Johari Window

Developed by psychologists Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham (hence the name Jo-Hari) the Johari Window is a 2x2 matrix model that captures key aspects of the interplay of our socio-psychological selves in communication.

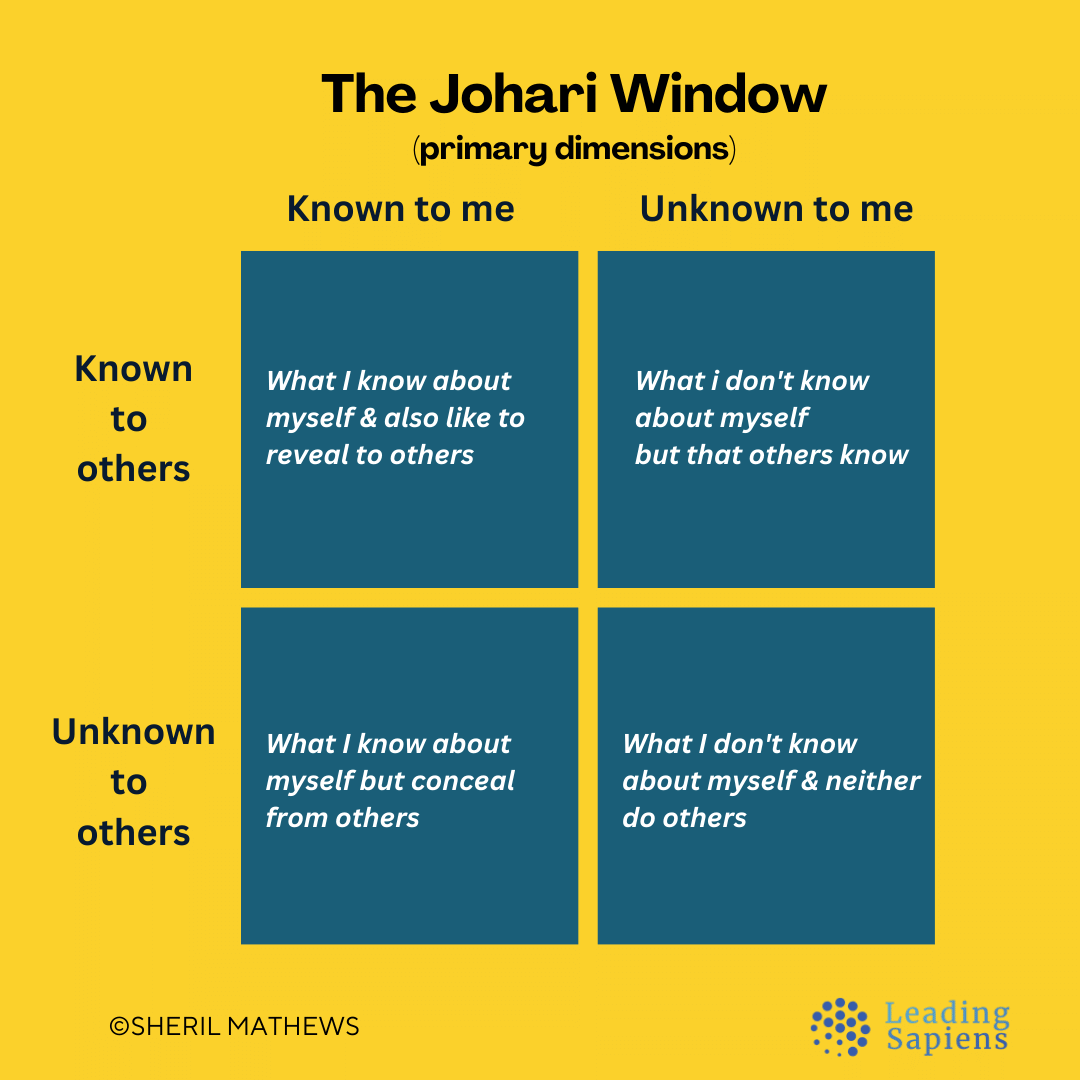

The two dimensions of the matrix are:

- Self-Knowledge (aspects of ourselves that are known/unknown to us)

- Others' Knowledge (aspects of ourselves that are known/unknown to others)

The primary improvements based on the tool focus on:

- Increased feedback (to increase self-knowledge)

- Increased exposure and self-disclosure (to increase others’ knowledge about us)

Joseph Luft [3] explains:

The four quadrants represent the total person in relation to other persons. The basis for division into quadrants is awareness of behavior, feelings, and motivation.

Sometimes awareness is shared, sometimes not. An act, a feeling, or a motive is assigned to a particular quadrant based on who knows about it. As awareness changes, the quadrant to which the psychological state is assigned changes.

4 quadrants of the Johari Window model

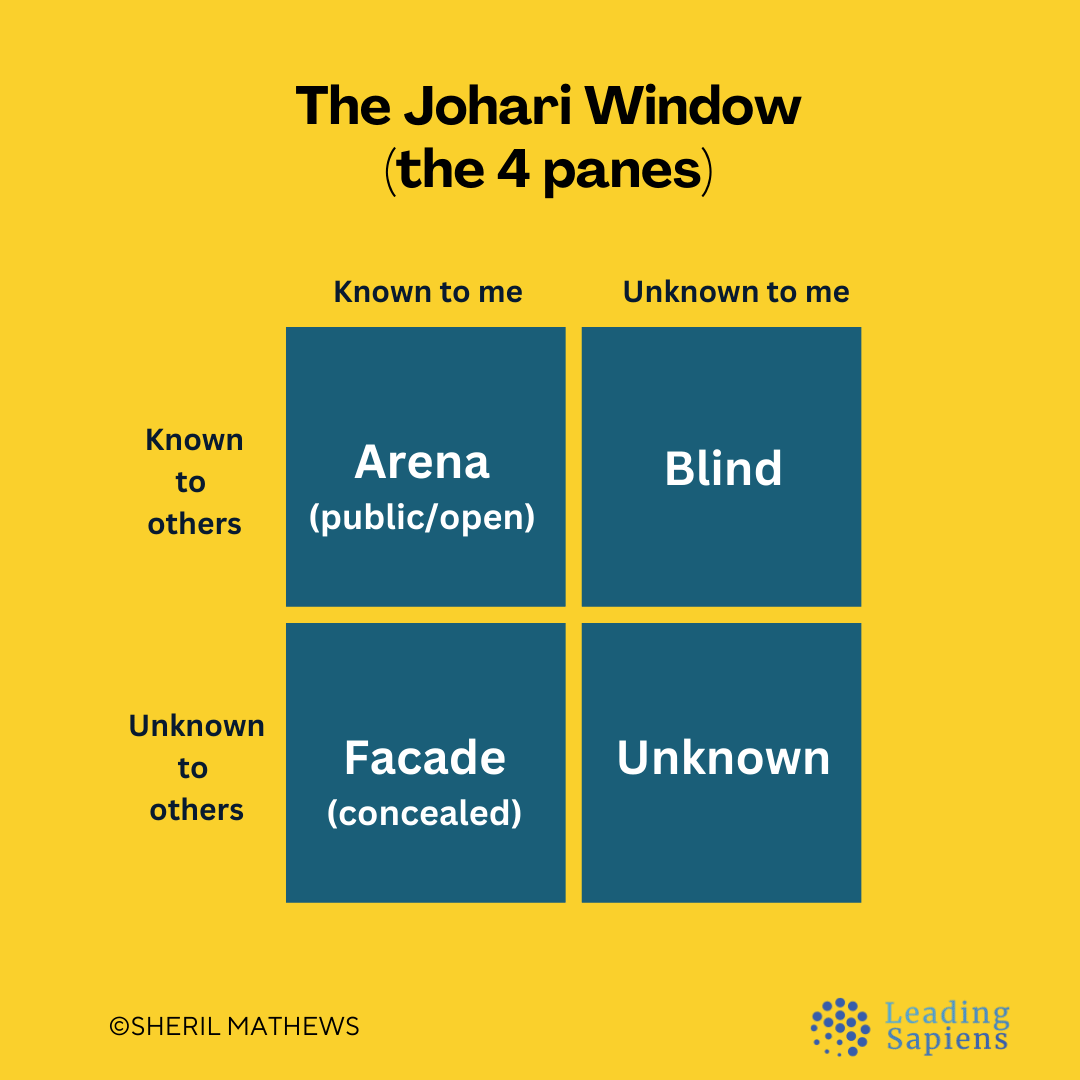

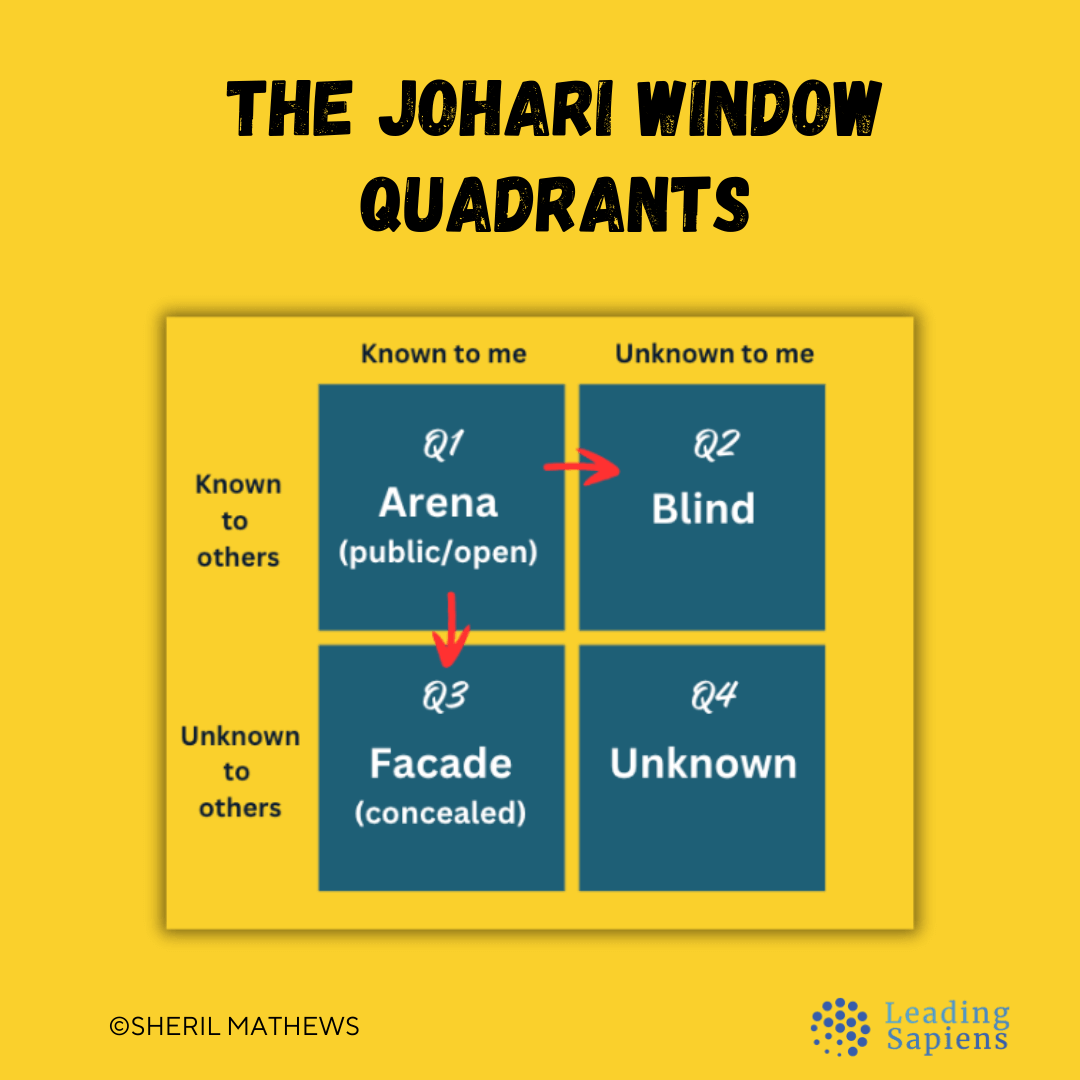

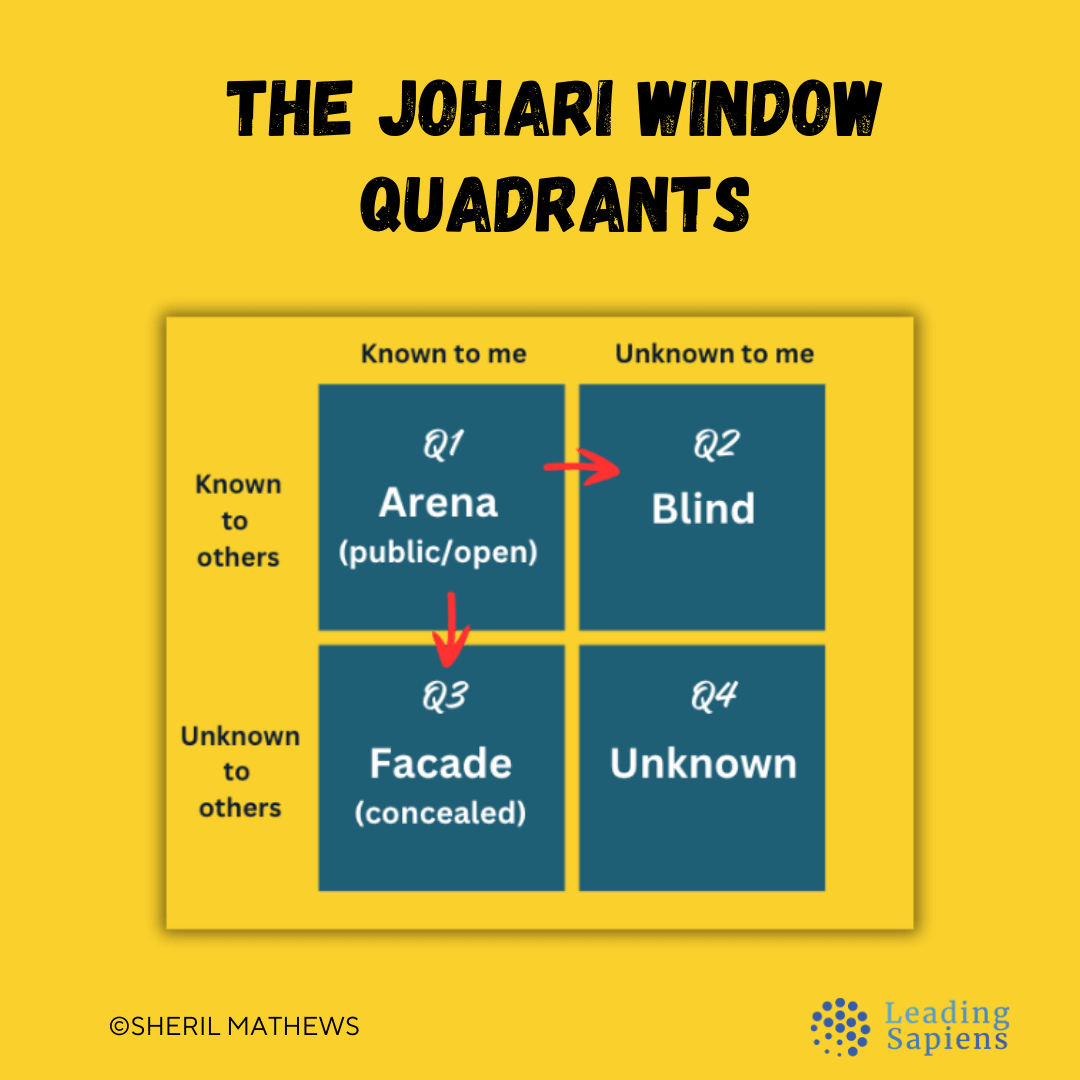

Using the two primary dimensions, the window creates 4 panes or quadrants:

- Quadrant 1, the open quadrant or The Arena

- Quadrant 2, the blind quadrant or The Blindspot

- Quadrant 3, the hidden quadrant or The Facade

- Quadrant 4, the unknown quadrant or The Unknown

Couple of pointers:

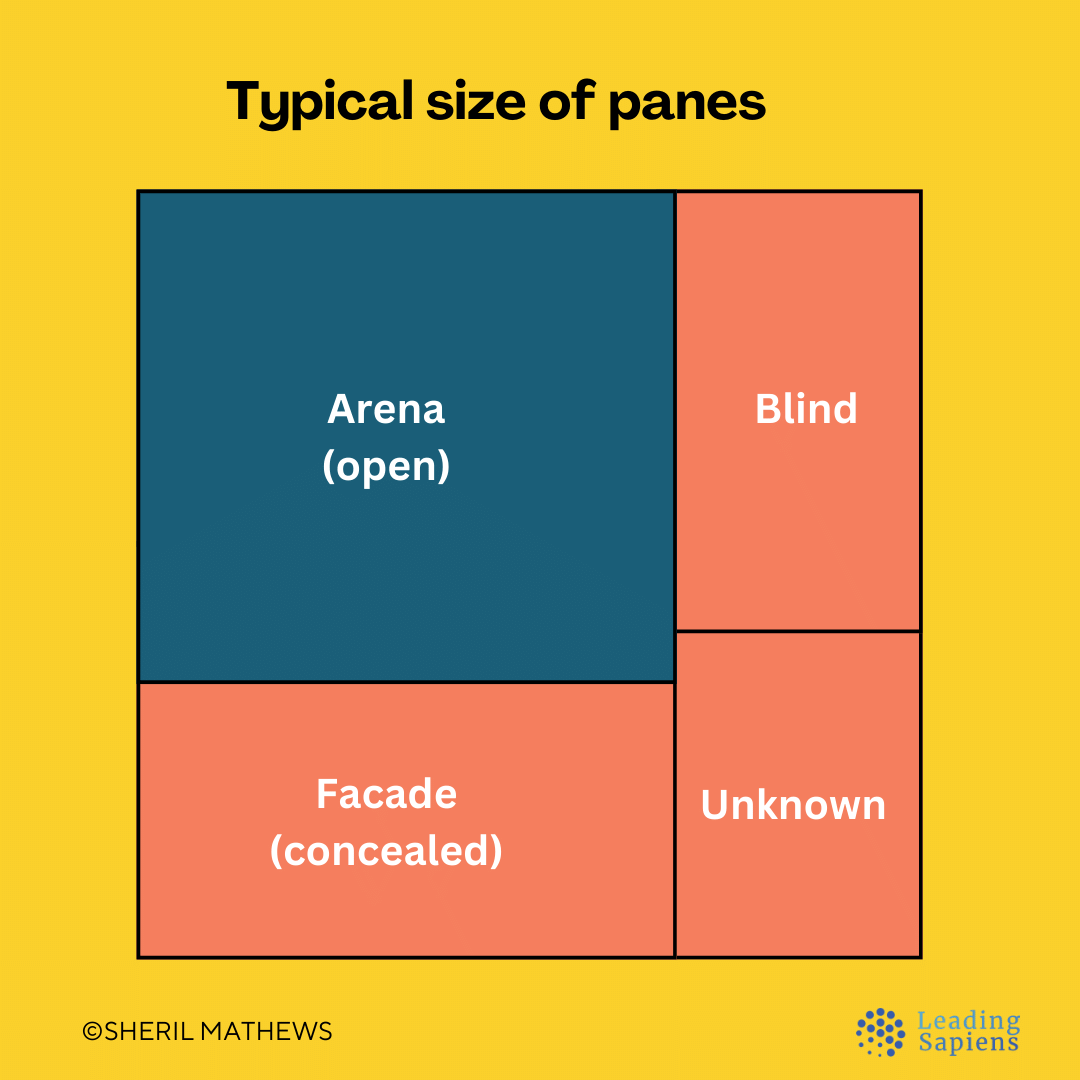

- The quadrants are not fixed in size. They vary with the person (more below). Change effort means an attempt to change the pane sizes.

- Lines separating the quadrants are akin to “shades” that can be lifted. More disclosure and feedback means opening of the shades and the quadrants changing in size.

Let’s look at each of the panes/quadrants more closely.

Quadrant 1 - The Open Quadrant

This is the public space. It's the part of ourselves — behaviors and feelings — that we’re aware of, and so are others. All information is known to all parties. We move freely within this space and it fosters open communication.

When operating in this zone:

- We're naturally trustworthy.

- We share information easily and more receptive to feedback.

- It requires confidence and self-assurance.

Larger this zone, the more adaptive and wider our repertoire. It means open communication and well-developed skills in sharing and eliciting. The more our communication falls in this area, the more effective we are.

More on the open quadrant:

Quadrant 2 - The Blind Quadrant

These are behaviors and attitudes that others easily see and recognize, but we're unaware of. A large blind spot can mean any or all of the following:

- low self-awareness

- scarcity of feedback

- no receptivity to feedback

- lack of listening skills

This often creates confusion and frustration because you don’t know what others are reacting to, which makes leaders far less effective. This zone is often ripe with opportunities for improvement for most folks. Making gains requires openness and courage to engage in feedback.

Quadrant 3 - The Hidden Quadrant

This is the private pane. These are aspects about ourselves we recognize and are aware of, but that we choose not to share. With leaders, this can be particularly problematic if they assume that others are, in fact, aware.

Hiding behind or putting up a facade is energy consuming and can be tiring when done for long stretches, especially if your profile requires you to have a larger open area. You also end up coming across as inauthentic and not trustworthy.

Quadrant 4 - The Unknown Quadrant

These are aspects of us that are unknown both to ourselves and others. A large unknown area makes you an unpredictable entity. We're essentially a mystery to others. This increases the risk of misunderstandings and sending the wrong "vibes".

Change and the Johari Window

Luft [3] gives key pointers on the nature of change and how it affects each quadrant. He calls it the "eleven principles of change":

- A change in any one quadrant will affect all other quadrants.

- It takes energy to hide, deny, or be blind to behavior which is involved in interaction.

- Threat tends to decrease awareness; mutual trust tends to increase awareness.

- Forced awareness (exposure) is undesirable and usually ineffective.

- Interpersonal learning means a change has taken place so that quadrant1 is larger, and one or more of the other quadrants has grown smaller.

- Working with others is facilitated by a large enough area of free activity. It means more of the resources and skills of the persons involved can be applied to the task at hand.

- The smaller the first quadrant, the poorer the communication.

- There is universal curiosity about the unknown area, but this is held in check by custom, social training, and diverse fears.

- Sensitivity means appreciating the covert aspects of behavior, in quadrants 2, 3, and 4, and respecting the desire of others to keep them so.

- Learning about group processes, as they are being experienced, helps to increase awareness (enlarging quadrant 1) for the group as a whole as well as for individual members.

- The value system of a group and its membership may be noted in the way unknowns in life of the group are confronted.

The Johari Window and self-awareness

There are two key reasons why understanding and utilizing the Johari Window is effective for increasing self-awareness in leaders:

- Information bias: WYDKYDK

- Honest feedback is a rarity

Information bias

Researchers have consistently found the most frequent cause of leadership derailment was "insensitivity to other people". They found that leaders consistently "behave in ways that actively derail their careers". What makes this so hard? Not knowing "what you don't know you don't know" aka WYDKYDK.

This means leaders:

- frequently get misinterpreted

- have trouble building trust

- appear inauthentic

- are ineffective at interpersonal relationships

When humans communicate, we don’t tell others what we actually think. And others don’t tell us what they actually think. Why? Because we would rather not offend anyone. This keeps the social machine well-lubed and working. But it's a liability for leaders.

Your position in the hierarchy is inversely correlated with the amount of accurate feedback you get — the higher you go, the less feedback. Many end up operating in echo chambers where their opinions and agenda are simply getting parroted and reflected back, aka the CEO disease.

Leaders never really understand their impact on others, or what they might be doing wrong, ultimately leading to career derailment.

Honest feedback is a rarity

The temptation to tell a chief in a great position the things he most likes to hear is one of the commonest explanations of mistaken policy. Thus the outlook of the leader on whose decision fateful events depend is usually far more sanguine than the brutal facts admit.

— Sir Winston Churchill, The World Crisis

The Johari Window model shows why honest, critical feedback is not only hard to give, but equally hard to receive. Unless you “reveal” what you see that I don’t, there’s no chance for me to reduce my blind quadrant. By definition I cannot access it without using external help.

But because of social norms, this never happens. Honest feedback would mean going against socially accepted rules of concealing, and potentially causing pain & discomfort to the other person.

And it's never going to happen when there's a power differential between the parties involved.

“I want you to tell me exactly what you think of me … even if it costs you your job.”

- Boss in a New Yorker cartoon

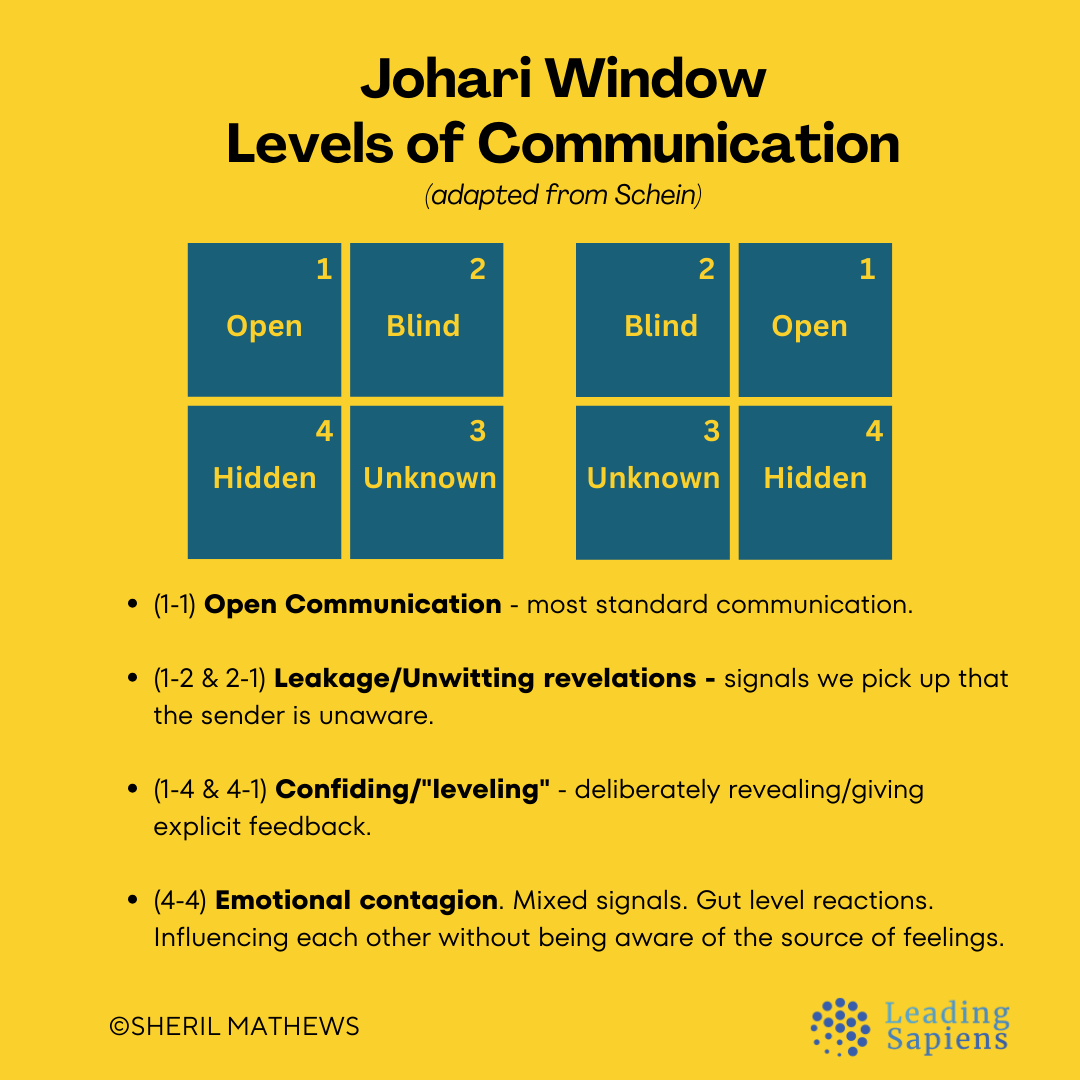

The Johari Window and managerial communication

How managers seek and share information in the context of the Johari window creates some unique styles. Exposure means how much they openly divulge opinions and share information. Feedback means how much they seek exposure and information from others.

This creates 4 distinct styles of managerial communication [7]:

The Turtle

These are managers low in both exposure and feedback, and thus unaware of themselves and of others’ feedback. They seem aloof, even anti-social.

The Interrogator

These managers are constantly seeking information (high feedback) but won’t divulge anything (low exposure) on their part. It’s a one-way street without mutual give and take. Without the exposure, others are kept guessing. Because their facade/hidden area of unshared opinions doesn't get tested, this limits their range and effectiveness.

The Bull in the China Shop

These are folks with large blindspot zones (high in exposure, low in feedback). Characterized by low self-awareness of their impact, except others can clearly see the issues. This is more likely when managers don’t listen well, and trust is not high enough where others share feedback.

They often come across as autocratic and ignorant – too hung up on themselves and not paying enough attention to elicit feedback, both good and bad. Others don’t get a chance to participate and trust doesn't get built.

The Ideal Manager

They're characterized by openness, high self-awareness, non-defensiveness, and free flow of information. Basically, a good combination of high exposure and high feedback. This is what managers need to aim for – everyone knows where they stand, have a clear understanding of their impact on others, and good at both sharing and eliciting feedback.

Without skill and tact, high exposure can come across as being naive, and also requires a high degree of emotional intelligence.

More: Johari Leadership Archetypes

The Johari Window in leadership coaching

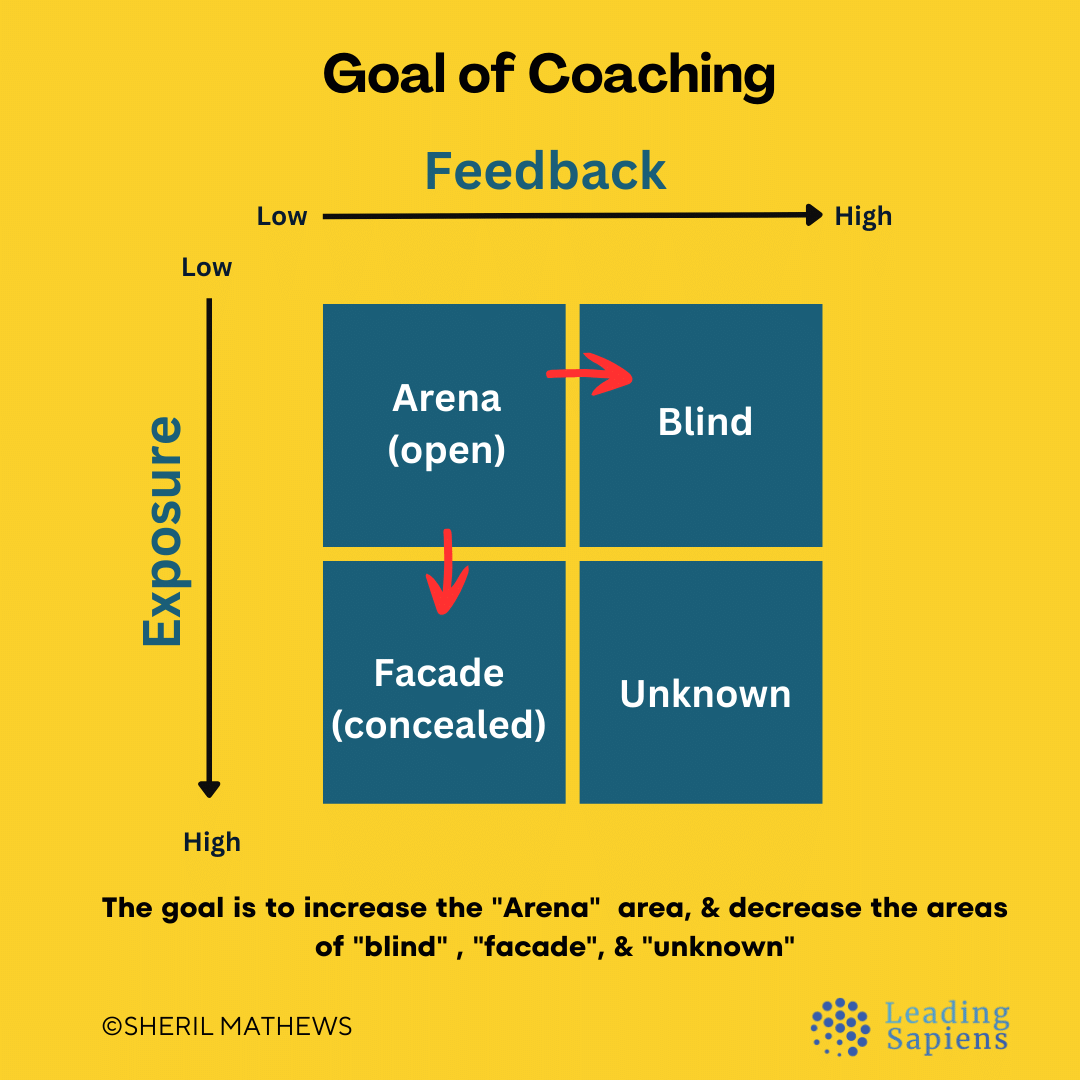

The primary aim in coaching, and other self-development efforts, is to increase your capacity by changing the size of the four quadrants.

In effect, leadership coaching tries to:

- Increase your Arena zone. This doesn’t mean a tell-all, but instead can be very specific to a given context and situation, and done tactfully.

- Shrink your facade and blind spot areas.

- Surface the unknown by creating experiments and testing out hypotheses.

- Help to see yourself as others really see you.

- Become better observers of ourselves.

This is achieved using a combination of:

- Actively seeking feedback.

- Learning to increase exposure through skill and tact.

- Recognizing self-created limits, boundaries and pushing through them.

- Designing observations and testing.

- Engaging in a regular cadence of active skilled reflection.

- 360-degree feedback organized in the context of the panes.

- Creating a “safe” environment for more accurate, candid feedback that highlights blindspots and facades.

The Johari Window and entire organizations

In senior leadership roles, you also have to be mindful of the Johari Window aspects of your team members, organization and even the whole company. The 4 areas of organizational self-knowledge would look like:

- The open area represents things the organization knows about itself, and that outsiders also recognize. This includes the organization's vision, values, culture, strengths and weaknesses. The more an organization engages with stakeholders through communication, feedback and introspection, the larger this pane grows.

- The hidden area covers things the organization knows but doesn't reveal. Every organization has secrets. This isn't necessarily bad, but too much hidden knowledge can limit effectiveness. Sharing more internally and externally expands the open area.

- The blind spot contains unknown unknowns - weaknesses, challenges and external perceptions the organization is oblivious to. This can be reduced through environmental scanning, feedback surveys and external advisory boards.

- The unknown area covers knowledge outsiders have about the organization, but the organization does not. This intelligence can be gleaned through open inquiry, soliciting input, and building trust with both partners and critics.

Reflection exercise and pdf worksheet

Use the below questions as a reflection exercise both at the individual and team levels:

- Do you seek/elicit critical feedback? How can you get better at it?

- What aspects of yourself do you hide?

- How big is your “facade” pane? How can you reduce it tactfully?

- Do you withhold information from your team members? Why?

- What potential blindspots are there based on recent performance feedback or 360 reviews? Do you agree with them?

- What problems are you having and are they related to your facade or blindspots?

- What are the opportunity costs of maintaining a facade or not recognizing blindspots?

- Are you aware of key developmental areas where you need the most help?

Related reading on the Johari Window

Below are some additional articles that build on many of the concepts discussed:

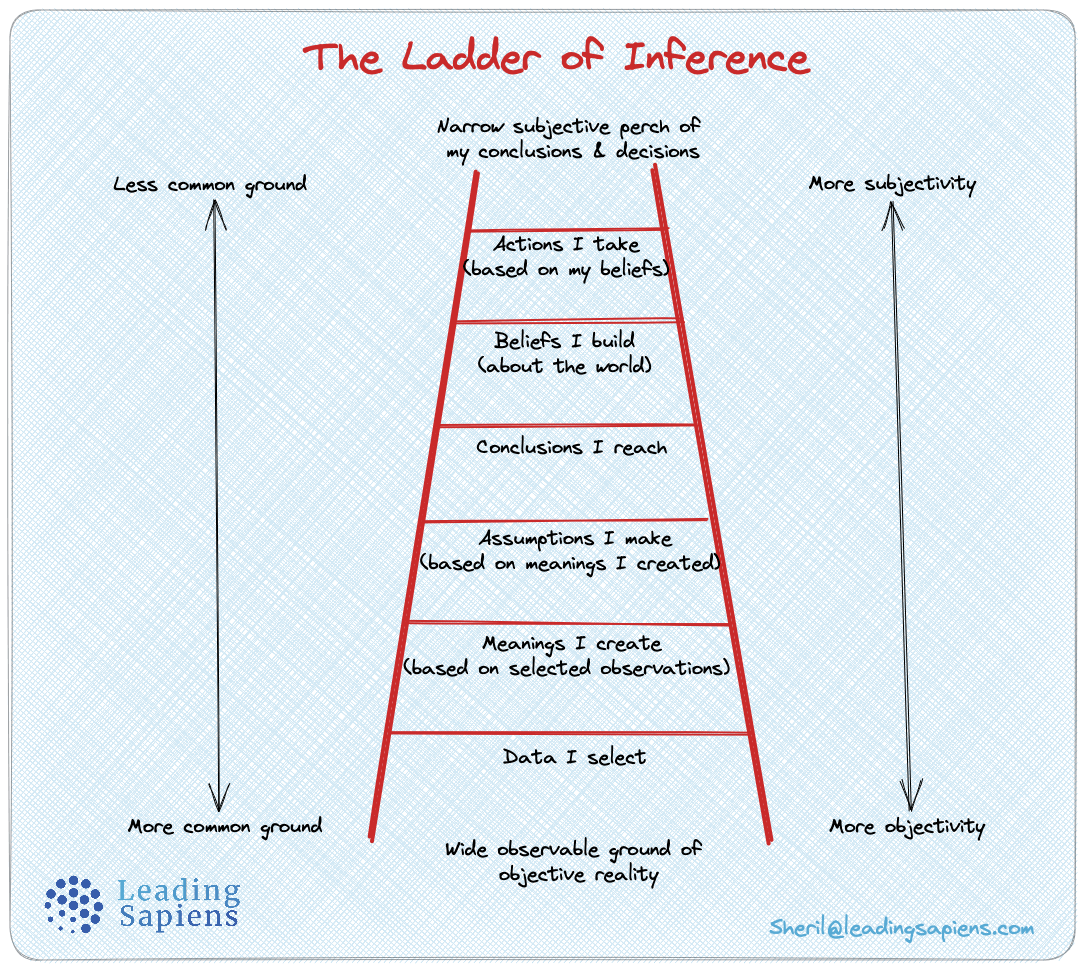

- The ladder of inference is a useful tool to understand how we selectively filter information to jump to conclusions and that can lead to misunderstanding:

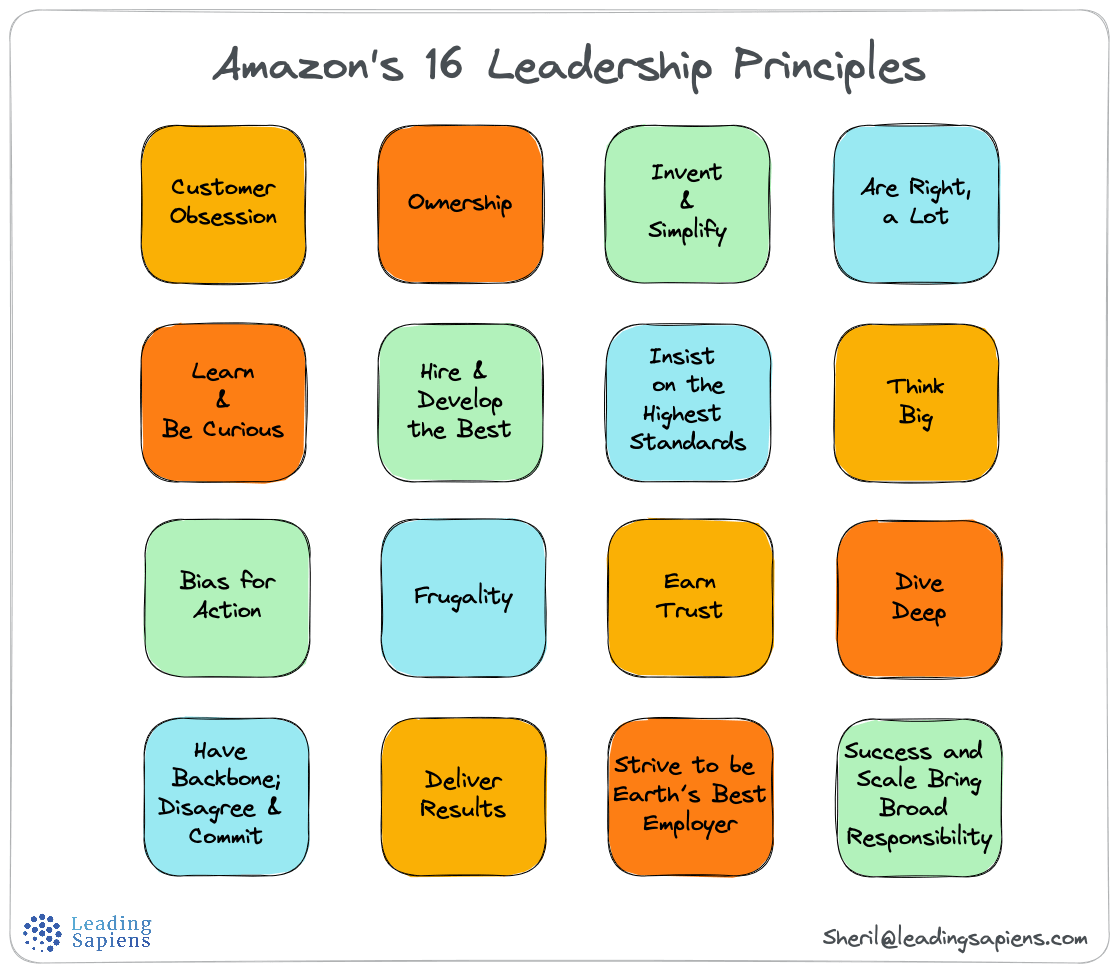

- Earning trust and being self-critical are key aspects of the 16 leadership principles at Amazon. The Johari window helps with building those skills. More on Amazon's leadership principles:

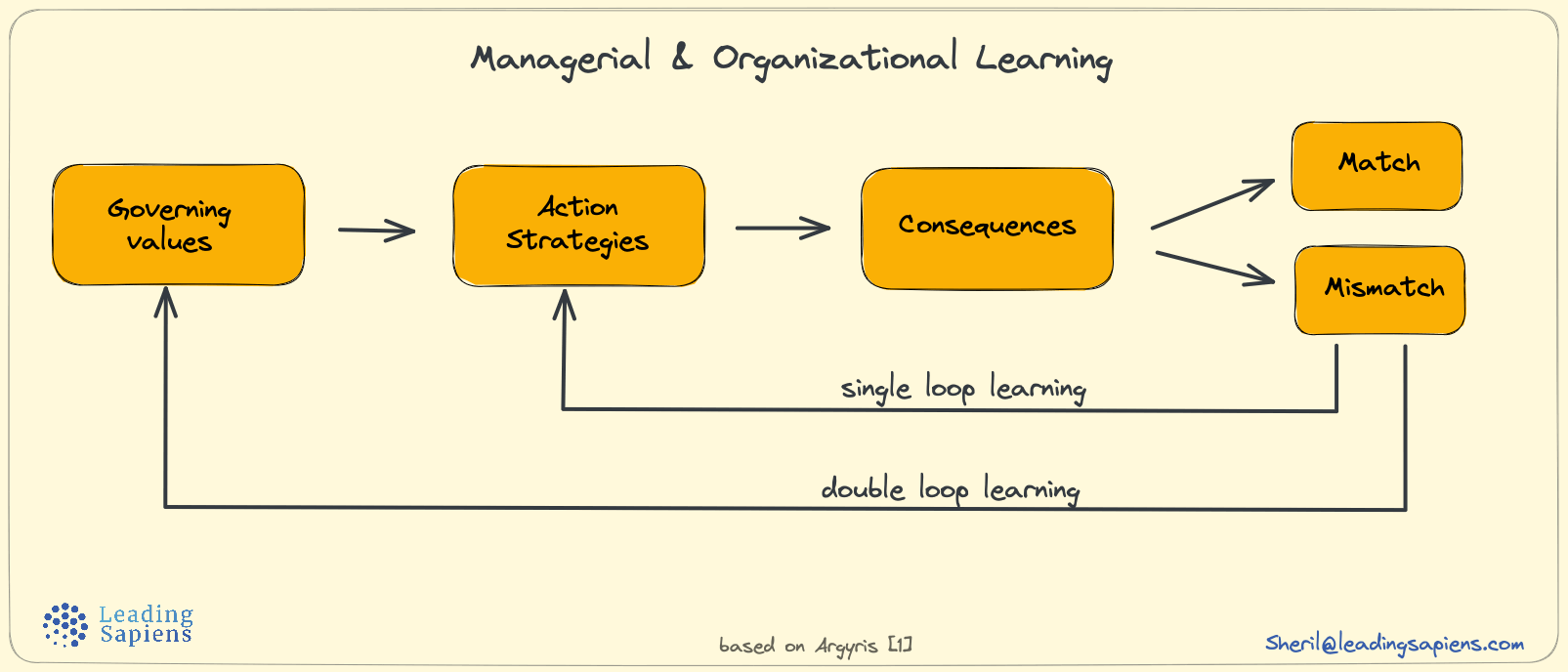

- Self-development is a key aspect of leadership effectiveness and requires getting good at what's called double-loop learning:

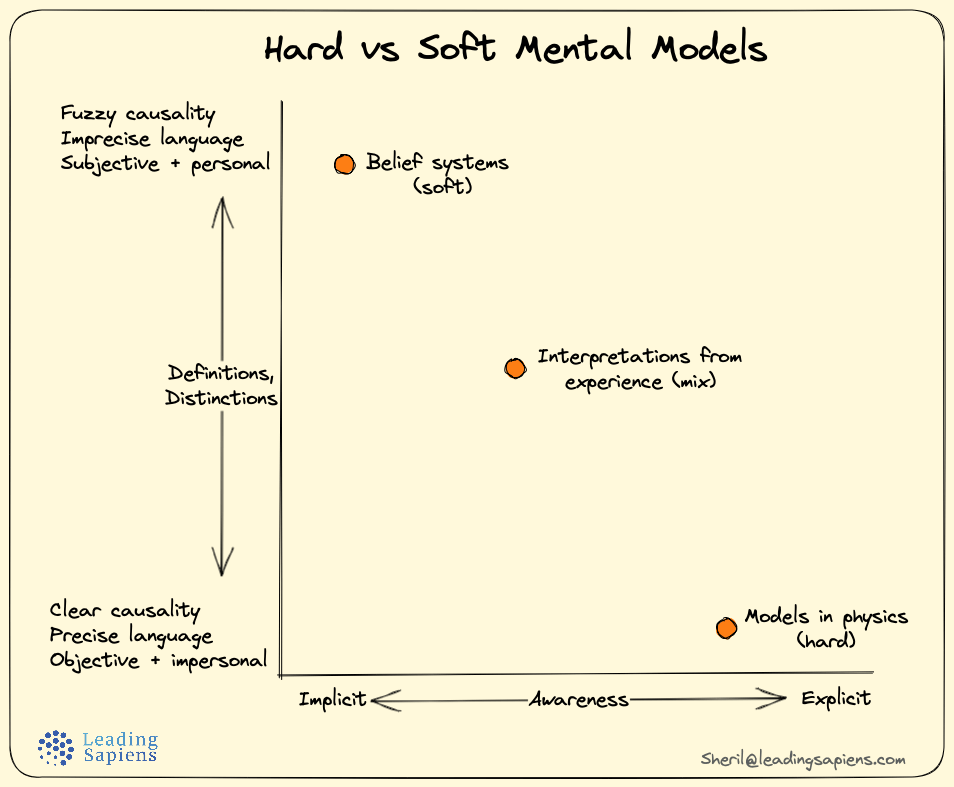

- A similar notion to blindspots and facades that coaching tackles is to identify unhelpful but hidden mental models:

Sources

- Hanson, P. (1973). The Johari window: A model for soliciting and giving feedback

- Luft, Joseph, & Ingham, Harry, (1961). The Johari Window: A Graphic Model of Awareness in Interpersonal Relations

- Of Human Interaction by Joseph Luft

- Process Consultation Revisited by Edgar H. Schein

- Humble Inquiry by Edgar H. Schein

- Organizational Behavior by Linda K. Stroh , Gregory B. Northcraft , Margaret A. Neale

- The Encyclopedia of Leadership by Bruce Klatt, Murray Hiebert

- The New Johari Window by William Bergquist