Language, because of its ubiquity and obviousness, does not get much attention from leaders and organizations as an area for improvement. But this is a missed opportunity.

Even when they do focus on communication, courses and training programs take a simplistic view far removed from the realities and complexities of organizations. In this article, we take a deep dive into the hidden role of language in effective leadership communication.

Leadership happens in language

Leadership happens in the social and human domain and language underlies both of these domains. Ignoring language and communication and assuming it as a given is a missed opportunity for leaders.

While most of us can get through our day without having to pay attention to these aspects, as leaders rise higher in their organizations, the numbers of constraints, coupled with the high levels of uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, increases. This is where understanding language in its several dimensions can be a game-changer for leaders seeking to increase their effectiveness.

Our research in this area and our applied work in the area of leadership development have led us to understand the phenomenon as a process of social influence that is very much informed by and shaped by communication.

The process involves both verbal and nonverbal communication and is defined by followers as much as by leaders.

We believe that there is also a need to advance a more expansive view of communication, one that represents communication as a symbolic process that shapes the human experience.

– Brent Rubens & Ralph Gigliotti [1]

I am not a philosophy or language major, but as I understood more about the pervasiveness and hidden dimensions of language, I was surprised how most schools and courses do not talk about or emphasize it’s potential applications in leadership. Even when they do, these aspects are taken for granted and not sufficiently illuminated.

Below are ten different “orientations” to language and leadership communication that can radically change your approach to organizations and people, and increase your effectiveness in working with them.

By orientation I mean an approach to, or a framework of language. Your approach to navigating earth would be different if you had a framework of a flat earth vs that of a round earth. This goes back to Thomas Kuhn’s notion of paradigms and paradigm shifts. [14]

Some of these will not be intuitive and will take some getting used to. I suggest approaching it as “trying something on” when you are at a store. Try and see “whether it fits” with your own reality and experience. As you understand and see more for yourself, you will start noticing the nuances.

1. The conduit model orientation

The single biggest problem with communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

- George Bernard Shaw

The traditional way of looking at language and communication is that of a tool or series of symbols to represent reality. This is the standard default orientation for all of us and this is how we intuitively look at language and communication- as a way to describe a pre-existing, pre-determined reality and as a way to convey information.

Even the jargon that we use on a daily basis reflects this bias. For example we use the terms “convey” and “communication channels” as if information is like water that needs to be transported.

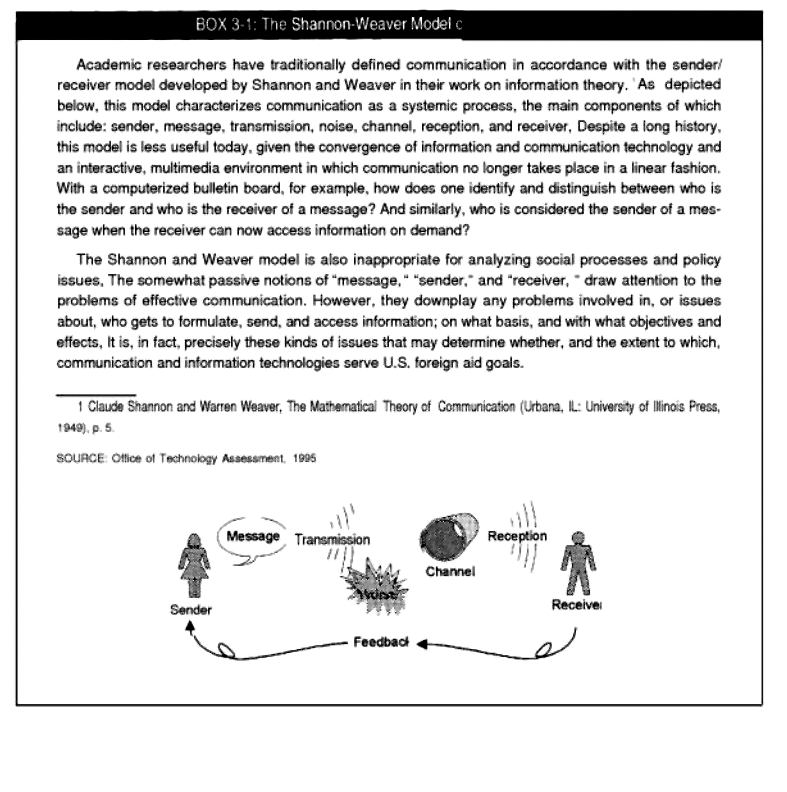

The underlying model in this orientation is that of the radio transmitter and receiver model also known as the sender-message-receiver model put forth by Shannon and Weaver in 1949. [2]

You have a certain set of information, I have my own, and we use communication as a conduit to exchange this information. If both the sender and receiver are in good working order and the “fidelity of the data” is good we have good communication.

Unfortunately this is an oversimplification when it comes to human communications.

This orientation drives the bulk of the “communication improvement” efforts where we try to perfect the “sender” of the information by working on the sender’s communication skills, delivery and so forth.

2. The interpretation/meaning model orientation

Unlike the receiver in the radio-transmitter model, the receiver in this case is another human being. And human beings are self-enclosed, meaning-making machines themselves.

This means we cannot “transmit” meaning to each other. We have to make our own meaning.

We interpret whatever is being said through our own set of filters made up of stories, meanings, and mental models that we have acquired over time. This is why, as all managers know, the same set of statements for a given situation can be interpreted very differently based on who is listening on the other end.

[I]t is apparent that in some situations, the communication “luggage” of one individual does not necessarily align all that well with the expectations, attributes, outlooks, states, and orientations of others with whom they are engaging.

Generally speaking, the greater the extent of mismatch, the less the likelihood that message sent will equal message received.

– Brent Rubens & Ralph Gigliotti [1]

This is where the “interpretation model” of listening comes in. The receiver is a human being who is “interpreting” the “information” that is being transmitted. While this is obvious to a large extent, most of the time when we communicate as leaders and managers, we tend to ignore or forget this basic fact.

The interpretation model is also another reason why we cannot expect our message to be understood, let alone embraced, from one great speech or presentation. If it is behavior change or culture change that we are seeking, it has to happen over several exchanges and through several modes and methods.

A systems approach, along with the more recent work in CCO(communicative constitutive organizations), underscores the limitations of the linear meaning-transmission or information-exchange views of communication and reminds us that single messages and single message-sending events seldom yield momentous message reception outcomes.

Rather, communication and social influence are parts of an ongoing process through which messages wash over individuals—somewhat analogous to waves continually washing upon the shore.

While the influence of any single wave is likely to be limited, over time, these messages shape the sensibilities and responses of receivers, much as waves shape a shore- line.

The exceptions to this subtle process are those rare, life-changing messages that can have a tsunami-like impact on message reception.

– Brent Rubens & Ralph Gigliotti [1]

3. Language is pervasive yet hidden

Like fish in water, we are surrounded by it but don’t pay attention to it. We see through the lens of language unaware of it’s presence. As Martin Heidegger put it, language uses us rather than us using language. [9]

Language is not only content; it is also context and a way to recontextualize content.

We do not just report and describe with language; we also create with it. And what we create in language “uses us” in that it provides a point of view (a context) within which we “know” reality and orient our actions.

– David Boje, Cliff Oswick, Jeffery Ford [10]

We cannot describe something or discuss something without having the language for it. Even for terms we do not have language for, we still have to express it using language. Thus as leaders, it is worth paying attention to the language we use that creates our reality.

Reality is more malleable than it appears at first, especially in social systems like leadership and organizations. This is the core difference that Korsybski pointed out between “engineering systems” and “social systems” . He coined the famous distinction of “the map is not the territory”. [15]

The map is but one description or one attempt at representation of the territory but it can never be the same as the territory. There is a lot more to the territory than what’s depicted on the map.

It’s the same for language. Whatever descriptions and explanations we have for a given situation is but one attempt at it. Once leaders understand this, it opens up a new set of opportunities for seeing situations differently; situations that earlier looked immutable and unchangeable.

4. Reality is created through language

Another hidden aspect of language is that we create our own reality through language. Reality that is constructed by us and constructed in language.

For any given situation, there are multiple possible interpretations of it. Your understanding of yourself and your myriad situations and projects lives in language. This includes your understanding of your teams, organizations, customers, stakeholders, and so on.

Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world.

In our endeavor to understand reality, we are somewhat like a man trying to understand the mechanism of a closed watch.

He sees the face and the moving hands, even hears its ticking, but he has no way of opening the case. If he is ingenious, he may form some picture of a mechanism which could be responsible for all the things he observes, but he will never be quite sure his picture is the only one which could explain his observations.

He will never be able to compare his pictures with the real mechanism, and he cannot even imagine the possibility or the meaning of such a comparison.

– Albert Einstein & Leopold Infeld in The Evolution of Physics [3]

How we understand and portray a given situation determines to a large extent how our teams perceive it. This is true especially in complex situations where there is no one clear solution or preconceived answers.

5. The action and commitment orientation

This is the language-action philosophy of JL Austin and John Searle, where we create action through language instead of just representing and describing something. [7] [8] [13]

When you ask someone out for lunch you create something in your future that did not exist before and you create it through the use of language. It is a specific usage of language called Requests. And when the person receiving the request accepted your offer they were using a specific type of language called Promises. They were making a Promise to you by accepting your Offer.

We do this everyday without even realizing it. The trick is to learn to leverage these aspects of language to design a future that we want to build rather than by accident or pure luck.

We also make commitments through our use of language in conversations. And it is these commitments that drive our actions and consequently our results and performance. Thus language is directly tied to our performance.

Setting objectives and goals is a good example of making commitments through language except we can be much more effective once we know how to leverage language. Setting objectives is all but one use of this particular orientation of language.

6. The generative orientation

This is the aspect of language where you are creating a new reality, a new world, or a new future using language. You are bringing forth possibilities that did not exist before that particular utterance.

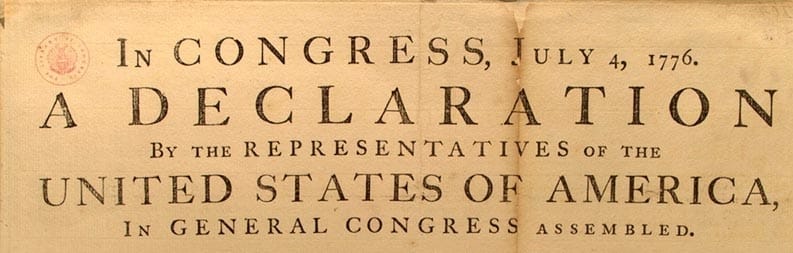

This type of use of language is called a Declaration and they are one of the most powerful ways to use language, but one that we use sporadically and not as effectively.

The ultimate example of the power of this type of language is the US Declaration of Independence. Using a declaration the US declared itself as independent of the crown and as a result created a new reality.

The world before the declaration and after the declaration was completely different. But the only thing that changed was language.

Before the declaration, the Americans were rebelling subjects, and after the declaration, they became entities on their own and an enemy nation to the Crown.

The range of opportunities and potential for action was completely redefined by the declaration.

7. The temporal orientation

Human beings are the only living creatures that experience life as having a past, present, and future. For all the others there is only the present moment. Even for us, physical reality is the only way to access the present.

Neither the past nor the future exist as physical realities. The past is a series of present moments that are gone and the future is a series of present moments that have not happened yet.

And yet, the past and future is accessible to us through language. They “exist” as memories and concepts. Both of them are built in language, and thus accessible to us.

Human beings are meaning-making and story-telling machines. We need to have meaning in everything we do and stories are our primary means of making sense of situations.

The way we act in the present moment is based on the stories we have of our past and the future that we think we are going into. Our actions are directly correlated to how a certain situation, our present and our future, occurs to us. And this is built in language.

8. Our mental models are built in language

The concept of mental models is well known in the cognitive science and neuroscience arenas. Essentially our brain is a predicting machine that predicts based on preexisting models that it has created over time.

The normal human brain that is the subject of study in neuroscience is a “languaged” brain. It has come to be the way it is through a personal history of language use within an individual’s lifetime.

It also actively and dynamically uses linguistic resources (the categories, constructions, and distinctions available in language) as it processes incoming information from across the senses.

– Lera Boroditsky [4]

These models are “built in language”. There’s a certain story we are telling ourselves about a given situation and it is but one version. And that story is built in language. This means that by changing the language we can change the story. This is easier said than done as these are ingrained patterns and habits we have learned over several years.

Each of us over time has built what Kenneth Burke calls “terminisitic screens”.[11] [12]

Words link together and form filters, or screens, that allow us to see in certain ways and blind us to the alternatives, just as a red filter allows us to see some colors and not others.

Burke said: “Even if any given [terministic screen] is a reflection of reality, by its very nature…it must be a selection of reality; and to this extent, it must also function as a deflection of reality.”

– David Logan & Halee Fischer Wright [12]

These are a large collection of stories, words, and concepts that we know and understand, and through which we perceive and make sense of all the sensory inputs that come in.

Some neuroscientists call these our “vocabulary” of concepts. While we cannot operate without these concepts or mental models, we do not have to have a particular one.

9. Organizations as constituted of language

Our usual way of understanding organizations is through organizational charts, job roles and designations, the products, the processes, and the people involved. And this is a useful way of looking at them.

But another way of looking at organizations is through the lens of language – as made up of a network of conversations, commitments and processes that happen through language.

There is a new understanding of organizations that is gaining traction which is called CCO or communicative constitutive organizations- understanding of the organization as being constituted of its conversations and thus its language

Leaders need to understand how language is all pervasive and is an underlying framework in everything they do. In fact some of the most intractable problems tend to have their roots in the unsaid, the “undiscussables” and the “background conversations” that constitute the culture of an organization.

Organizations, despite their apparent preoccupation with facts, numbers, objectivity, concreteness, and accountability, are in fact saturated with subjectivity, abstraction, guesses, making do, invention, and arbitrariness . .. just like the rest of us.

Much of what troubles organizations is of their own making.

– Karl Weick in Social Psychology of Organizing [5]

While decreeing a certain behavior using our positional authority is one way to approach culture change, it tends to be short-lived. A more sustainable path is to examine and change underlying conversations and ensuing behaviors.

10. Accessibility of language for more effectiveness

Perhaps most important for leaders is the accessibility of language, because this is what makes language such a powerful tool to effect change and increase effectiveness.

Everything else being the same , what really makes a difference in someone’s leadership is “the network of unexamined ideas, beliefs and taken-for-granted assumptions” that go unexamined. [16] The good news is that these are “constructed in language” and thus can be worked on and rebuilt.

Human beings are the only beings who think about themselves and their actions. Other animals “are unable to separate themselves from their activity and thus are unable to reflect upon it” .

– Bruce Hyde & Jeffery Bineham [6]

Because language is recursive, we can talk about talk, we can write about writing and so on. It is a powerful tool for observation, analysis, and ongoing improvement which is not possible in other mediums.

Language is accessible by everyone because it is pervasive and we are constituted in it. This makes it equally available to everyone without specialized training.

A challenge and opportunity

The big challenge for leaders is not just to understand these different orientations but to employ them in practice.

To those in the discipline of speech communication, the notion that language is not merely representational, but provides the world with its meaning, is not a new one. But we suggest that while many of us understand this theory, far fewer of us live it.

In large part, most human beings are commonsense Cartesians. We spend much of our lives struggling with the way things “are,” rather than savoring the malleability that a constitutive view of language, fully distinguished, might lend our world.

To gain access to the generative nature of dialogue, one must be open to the power of language to create meanings.

– Bruce Hyde & Jeffery Bineham [6]

Understanding the role of language is essential if leaders want to leverage their role as meaning-managers, meaning-makers, sense-makers, and co-constructors of reality. This in turn is directly tied to leadership effectiveness.

The next time we are in “communication” it is worth considering which of these orientations we are using in practice and what our underlying assumptions are.

Are these assumptions true and how can we change them? Which understanding of language can be more helpful to solve the particular challenge that we are facing? Which understanding makes us more effective?

Related Reading

Footnotes and References

- Communication: Sine Qua Non of Organizational Leadership and Practice by Brent Rubens and Ralph Gigliotti

- Shannon-Weaver model of communication.

- The Evolution of Physics by Albert Einstein & Leopold Infeld.

- Language and the brain by Lera Boroditsky.

- The Social Psychology of Organizing by Karl Weick.

- From Debate to Dialogue by Bruce Hyde & Jeffery Bineham.

- Speech Acts by John Searle

- How to do things with Words by JL Austin

- Being and Time by Martin Heidegger

- Language and Organization by David Boje, Cliff Oswick and Jeffrey Ford

- Language as Symbolic Action by Kenneth Burke

- Rhetoric Unlobotomized by David Logan & Halee Fischer-Wright

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/speech-acts/

- The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas Kuhn

- The map is not the territory

- Jensen, Michael C., Werner Erhard, and Kari L. Granger. “Creating Leaders: An Ontological/Phenomenological Model.” Chap. 16 in The Handbook for Teaching Leadership: Knowing, Doing, and Being, edited by Scott Snook, Nitin Nohria, and Rakesh Khurana.