Managing effectively using data is all the rage today. But most of it is shallow "hard data". The real challenge is to get so called “soft data”. How do you get the real pulse of your teams, or your customer’s true opinion?

There’s a simple method that can tell you more than any amount of data. Most managers either don’t do it, or simply miss the point of the whole exercise. It’s the lost art of MBWA.

What is MBWA?

MBWA stands for managing by wandering around. Variations include wandering about, or walking about. The military calls it “battlefield circulation” while others call it “visible management”. Lean methodology calls it the “gemba walk”. But the core idea is the same.

It is to break through the walls of organizational bureaucracy by using informal communication channels. How? Simply by walking around and having direct one on one conversations. Sounds too simple? As with many simple ideas, it's not necessarily the method but the consistency of execution that makes it potent.

Managers and leaders can easily become ensconced in a disconnected reality of paperwork, functions, organizational silos and titles. It’s about getting out of that bubble and cutting through the typical hierarchy and filters to understand what’s really going on directly from the frontlines.

You can’t lead from your office/cubicle. You lead on the shop floor or, for that matter, in the customer’s or vendor’s place of business. You lead, damn it, by staying in direct touch with the action that matters. And it gets harder and harder and harder as the company gets bigger and bigger and bigger.

…the faster things change, the more important MBWA becomes. In fact, MBWA for me has become not a “thing to regularly do” but a metaphor for a way of life and style of leadership fit for eternity and, especially, fit for these crazy times.

MBWA means jumping directly into the fray, not via spreadsheets (which are important to the extent that they are realistic—few are) but through conversation at the proverbial “coal face”—where the grubby digging is done.

— Tom Peters in The Excellence Dividend

MBWA applies equally to the factory floor and to remote teams. With remote teams it can be harder, but I would argue even more important to do. In remote setups, almost all interactions become “scheduled” conversations that impose formality. The idea behind MBWA is to go past formal setups that restrict communication.

It can take any number of forms: informal one on ones, water cooler talk, hallway conversations, coffee chats, shop floor interactions and even schmoozing. The mechanism doesn't matter. The key differentiator is whether you do it, and how you go about it.

The terminology belies it’s simplicity. When done well it can be an effective way to build resilient teams and strong customer relations.

The rise and fall of MBWA

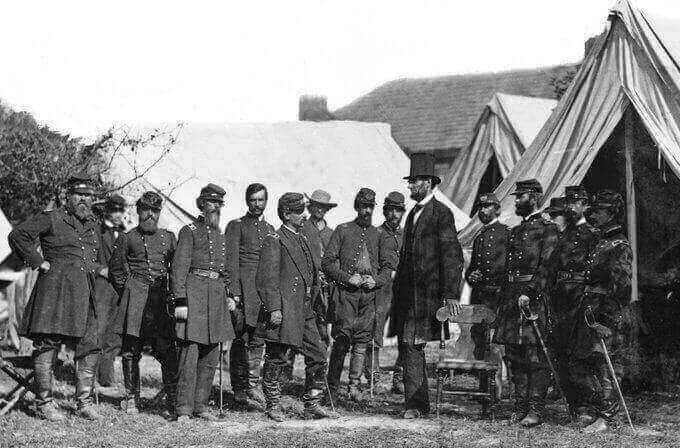

It's easy to dismiss it as just another fad, but one of the earliest practitioners of MBWA was President Lincoln. Recognizing that the White House was an ivory tower cut off from reality, he was regularly on the battlefront, once even getting shot. He sacked one of his generals for being too isolated. And back in the office, a majority of his time was spent meeting ordinary people.

MBWA originated at Hewlett Packard in the 60s and 70s, later popularized by the book In Search of Excellence in the 80s. But in the ensuing years, it’s popularity has waned. Why?

One major reason is easy access to lots of “data” giving managers the illusion of having an accurate or complete picture of reality. If anything, MBWA should be even more relevant now because it gives the exact kind of detail that data cannot capture. Often it’s just what’s needed to get a balanced view rather than one skewed by the smoke and mirrors of "hard data", which often ends up a mirage and fallacy.

One genuine conversation in the field or with a customer can give you more data than a hundred superficial surveys.

How not to do MBWA

Most articles focus on the “how” of doing MBWA. But that’s unnecessarily complicating it. It's far more useful to know how managers botch it up. Many of our default behaviors end up having the opposite effect of what MBWA is supposed to do. It's easier to be smart by not being stupid.

- Doing it for the sake of doing it. You do it because someone told you to, simply checking it off your list. To be effective, you have to be genuinely curious and actually care. People can sense when you are being superficial and simply want to get something done. You don’t want to turn this into cringe exercise for your folks or your customers.

- Trying to do “active listening”. Just listen and be present. For most folks active listening is simply a distraction. It makes you do too many things, and not enough of actual listening.

- Going in with a script. You have to be willing to be vulnerable. The moment you rely on script, it kills spontaneity and effectiveness. The “information” you are after can’t necessarily be pursued. Rather it has to ensue as a result of the rich interactions. When done wrong it can easily turn into micromanaging.

- Being the “coach”. Please don't. Rather, be willing to be coached. Too often coaching and "helpful pointers" derail the conversation and put folks on the defensive.

- Going in with an agenda. When you have agendas on your mind to actively get something out of it, you are not paying attention to what’s right in front of you. You miss out on a rich dataset because you are preoccupied.

- Dictating or preaching. Usually this ends up being a monologue or simply another form of micromanaging and trying to control the process. Listening and engaging should be the priority, not pontificating.

- "Catching" people in the act. The idea is not to ignore wrongdoing but instead focusing on what's going right.

- Going with an entourage. This is especially relevant to CEOs and execs. The idea is connection, not alienation.

Why most managers fail to do MBWA

Aimless wandering takes discipline.

— Tom Peters

Inspite of its effectiveness, most managers simply won't do it, and usually there are logical sounding reasons not to. Many others "intend" to, but never get around to doing it.

Some common reasons:

- They are afraid to hear exactly what they don't want to : the uncomfortable truth. That the customer dislikes the product, that no one is following the new initiative, or that the new process is in fact broken. It's easier to hide behind data or to wait for it passively.

- It doesn’t work right away and initially can feel like a waste of time.

- They think they already know everything there is to know or that they have all the "data".

- It risks looking foolish and “naive”, especially in the beginning when you’ve never done it. It requires a degree of vulnerability which most managers have been trained not to exhibit.

- They claim to not have the bandwidth.

- Listening well and asking questions takes work. Staying patient until something emerges is one of the hardest things to do.

- The unpredictability of the process causes uncertainty and anxiety which causes discomfort. We like the expected predictability and structures of formal meetings where everyone has a predefined role. The lack of structure forces you to step out of your normal roles. But that's exactly what makes it effective. Every engagement is unique and unexpected. It’s why the pros will do it while the amateurs will shy away.

- Disengaged managers will rarely do it. The process can be demanding, and requires commitment and energy.

- It can often look like schmoozing, meanwhile meetings look and feel like “real work” but the often it's the exact opposite.

- Some managers are afraid that it will be seen as micromanaging. Done the wrong way, it will surely come across that way.

- They think the “open door policy” is a good substitute for MBWA. It’s not. Most folks hesitate to “waste” your time. They come to you only when there’s a crisis, or when they have something important. But many large issues start off as seemingly unimportant roadblocks.

The average harried manager remains tied to her or his desk or screen and over time loses touch with reality. Advanced artificial intelligence may be reading faces on screens and assessing moods with some accuracy, but being “in touch” with all one’s senses and with every sort of player in the organization remains of the utmost importance, remains the heart of the matter.

True transformation (a word I usually avoid like the plague) will mainly come from a dozen new little habits, not some bullshit values statement that nine out of ten employees find laughable because the isolated boss is so unaware of the degree to which it has no impact or veracity in the field…where, to re-re-repeat myself, the real work, as always, is done.

...The good MBWA intentions are not fulfilled (for “good” reasons), and you end the day one more degree out of touch than you were when the sun came up. Soon, alas, you will become a MBM—Managerial Blind Man. Awash in numbers and spreadsheets, clueless about the real world—and, believe it, big data and algorithmic voodoo ain’t gonna save you, my friend.

— Tom Peters in The Excellence Dividend

Why MBWA is vital for effective leadership

Walking around enables the perceptive leader to judge the organization’s psyche, morale, readiness, toughness, inventiveness. He or she may hear valuable scuttlebutt, rumors, misinformation. Always being around is a way for managers to sense the cultural pulse of the company. Being in the fray is another way to spot future stars, notice behavior issues, observe interpersonal chemistry challenges.

…Walking around does not mean you have to help load the trucks or solve the big marketing problem, but it does mean you will know who are the good truck loaders and good marketing mavens, and who are not.

— Jeffrey J Fox in How to be a fierce competitor

1. Understanding your audience

MBWA helps you understand the “world of your audience” and thus informs all your interactions. It gives rich context when you communicate which enables a connected dialogue instead of a disconnected monologue. This is true not just for your own team but customers as well.

It's hard to build genuine relationships when you are detached from the realities of what your teams and customers face on a daily basis. And you will not get this from formal reports or feedback surveys.

Most folks are not good about communicating what troubles them. But catch them at different times of the day and you might get different answers. Measuring employee engagement can be done by questionnaires, but they cannot beat realtime one on one feedback from the field. Same for customer satisfaction surveys.

2. Going beyond instrumental communication

Most communication in organizations tends to be instrumental. It’s a means to an end and people pick up on it. Non-instrumental, non-hierarchical interaction is a rarity that enables rich, open exchanges.

Without having a mechanism to access the nuances, what you get through formal channels will always be devoid of depth. And neither can you game it or time it. You cannot show up once a year and expect the customer to “open up”. It requires investment of time, effort, and engagement, coupled with the risk of coming out empty.

The four star general Stan McChrystal, compares leadership to gardening, and MBWA is essentially the leader’s daily and primary task.

Gardeners plant and harvest, but more than anything, they tend. Plants are watered, beds are fertilized, and weeds are removed. Long days are spent walking humid pathways or on sore knees examining fragile stalks. Regular visits by good gardeners are not pro forma gestures of concern—they leave the crop stronger. So it is with leaders.

The military term is “battlefield circulation” and it refers to senior leaders’ visiting locations and units. ...Most of these visits had multiple objectives: to increase the leader’s understanding of the situation, to communicate guidance to the force, and to lead and inspire. A good visit can accomplish all three, but a bad visit can leave subordinates confused and demoralized.

Visits offer an opportunity to gain insights absent from formal reports that have passed through the layers of a bureaucracy.

— General Stanley McChrystal in Team of Teams

MBWA promotes ownership and engagement, and enables what Alvin Toffler called adhocracy — informal but highly adaptive organizational structures that are responsive. It works outside of standard organizational channels that tend to be one-to-many rather than bi-directional.

3. Balancing top down vs bottom up

Balancing top down and bottom up approaches to strategy is critical but rare. Folks on the frontlines are the ones in direct communication with customers and thus most aware. But they don’t have the top level view that executives might have. How do you bridge this gap?

By making sure there’s free flow of information not just top down but bottom up as well. MBWA enables this dynamic by building natural feedback loops. It bypasses organizational filters putting you straight at the source. Big problems often start small. If you are paying attention you can be ahead of the curve.

If you wait for people to come to you, you’ll only get small problems. You must go and find them. The big problems are where people do not realize they have one in the first place.

—W. Edwards Deming

4. Accelerating your learning curve

In modern knowledge work, knowhow tends to be concentrated in silos. More often than not, teams know a lot more than the manager. MBWA done consistently over time can literally be a crash course in what your team is actually doing, how they get it done, and the typical roadblocks. A good 50-70% of this stuff never surfaces in formal meetings or discussions because no one thinks it’s worth mentioning. But that’s exactly what makes it valuable to surface.

To manage one must lead. To lead, one must understand the work that he and his people are responsible for.

— W. Edwards Deming

Informal tacit knowledge often cannot be captured. The only way to access it is through informal mechanisms like MBWA.

5. Building trust

How do you build trust? One way is to consistently show up, not just metaphorically but literally. Visibility and credibility are more related than we think. Thugs don’t want to be seen.

MBWA gives leaders an opportunity to build relationships outside of hierarchy and instrumentality, through honest conversations and keeping things simple. It requires vulnerability and courage on the leader's part, and thus creates greater trust.

In organizations, real power and energy is generated through relationships. The patterns of relationships and the capacities to form them are more important than tasks, functions, roles, and positions.

— Margaret Wheatley

We humans have a need to talk and be heard. Formal team meetings or project meetings don't often address these needs. MBWA is an effective way to hit on many of the core aspects of what's needed for peak human performance.

6. Leveraging the technology of talk

MBWA allows a real conversation to evolve between two human beings and two peers, in contrast to the traditional manager-subordinate setup. In formal meetings, everyone shows up in their masks and behind their roles, which makes it hard to have a genuine, candid conversation.

Managers forget that conversations are the basic building blocks of organizations and that effective leadership is essentially effective conversations. MBWA is a potent framework to do just that.

Some questions to consider

- How many organizational layers does information filter through before getting to you?

- How do you get most of your information? Is it primarily through reports and emails?

- Are you intimate with the real problems on the ground?

- How does your team get their work done?

- Do you intimately know your team's pain points? What about your enduser/customer?

- Do you have a good pulse on your team's morale and your customer's satisfaction?

- Are you the first to know or the last to know when problems surface?

- How do you "balance out" your data?

Jack Welch once said,

There are only three measurements that tell you nearly everything you need to know about your organization’s overall performance: employee engagement, customer satisfaction and cash flow.

MBWA is an effective way to address at least two of those three important parameters. What else is there to do?

Sources

- The HP Way by David Packard.

- In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America's Best-Run Companies by Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman.

- The Excellence Dividend by Tom Peters.

- Team of Teams by Gen. Stanley McChrystal, with Tantum Collins , David Silverman, Chris Fussell.