Project Aristotle was a multi-year research initiative by Google to understand what made teams effective. Some of its findings, psychological safety in particular, were counterintuitive. It changed how companies viewed teams and performance.

Yet, a decade later, implementation remains challenging. I examine common challenges leaders face in applying psychological safety and other findings in actual practice.

How would you assemble a “world’s best team”? What key factors should you consider?

In 2012, Google embarked on a mission to build the perfect team. After studying 180+ teams over two years, they made an eye-opening discovery: individual talent matters far less than we usually think.

Background of Project Aristotle

With a nod to the Greek philosopher’s insight that “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts”, it sought to decode the mystery of why some teams consistently outperformed others.

Based on research and analysis of over 180 teams, they analyzed variables related to team composition, including individual personalities, experience and education levels, cognitive abilities, and managerial styles.

Initially, the results were baffling. Despite the volume of the data, it yielded little information on what differentiated groups. They weren't sure if they were asking the right questions.

Eventually, they discovered norms of people working together — unwritten rules and behavioral standards that establish expectations and govern interactions. Norms are the fundamental reality; they define how people actually behave as opposed to what they aspire to or what they say. They influence the levels of trust, vulnerability, and functioning of teams.

Contrary to Google's initial hypothesis, team composition turned out to be far less important than how the team worked together.

We were pretty confident that we’d find the perfect mix of individual traits and skills necessary for a stellar team – take one Rhodes Scholar, two extroverts, one engineer who rocks at AngularJS and a PhD. Voila. Dream team assembled, right?

We were dead wrong. Who is on a team matters less than how the team members interact, structure their work, and view their contributions. So much for that magical algorithm.

— Julia Rozovsky

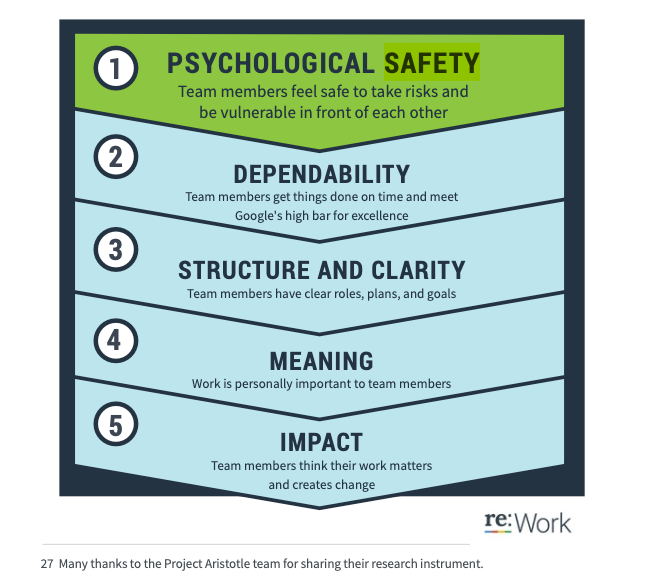

Google identified five key elements (in order of importance) that set successful teams apart:

- Psychological safety: Can we take risks on this team without feeling insecure or embarrassed?

- Dependability: Can we count on each other to do high-quality work on time?

- Structure and Clarity: Are goals, roles and execution plans on our team clear?

- Meaning of work: Are we working on something that's personally important for each of us?

- Impact of work: Do we fundamentally believe that the work we’re doing matters?

Psychological safety — a shared belief that the team environment is safe for interpersonal risk-taking — was identified as the most critical. In teams with high psychological safety, people feel comfortable admitting mistakes, asking questions, challenging ideas, and raising concerns without fear of negative consequences.

Psychological safety actually drives performance…when team members feel safe, they’re much more likely to ask for help. They’re much more likely to admit a mistake. They’re much more likely to try new roles and responsibilities, knowing that their team has their back—and, by doing this, they learn. And by learning, they become more effective.

— Julia Rozovsky

Implications of Project Aristotle

The findings changed how team effectiveness was commonly understood, shifting the focus from individual talent to team dynamics and psychological safety:

- Assembling the best talent was less important than the team’s social and psychological conditions.

- Introversion, personality types, and seniority were less significant than equal turn-taking in conversations and creating a safe space for everyone to speak.

- It emphasized that encouraging interpersonal risk-taking (e.g., asking “dumb” questions or admitting ignorance) was critical to success.

They emphasized leaders as facilitators of team dynamics, not just task managers. Leaders were responsible for:

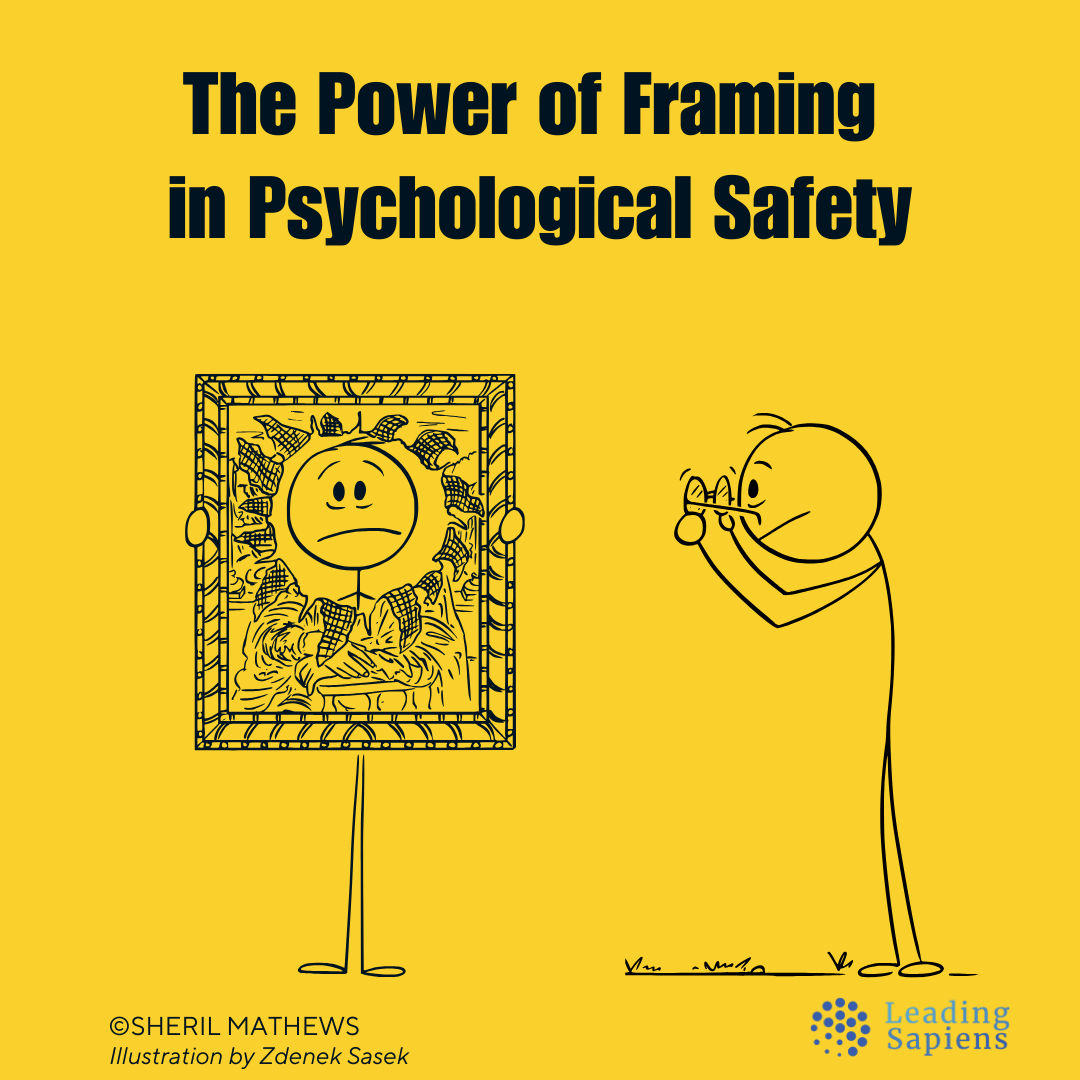

- Creating psychological safety by modeling fallibility, encouraging equal participation, and open communication. More on how leaders can use framing.

- Ensuring clarity and structure by setting clear goals and ensuring every team member understands their role and contribution to the team’s success.

- Creating meaning and impact by connecting individual tasks to the broader mission and vision.

- Emphasizing trust, openness, and collaboration over traditional performance measures.

After Project Aristotle, Google changed its management practices:

- Training managers to create psychologically safe environments by providing tools to encourage open dialogue and feedback.

- Developing a self-assessment tool for teams to evaluate themselves based on the five key dynamics, helping to identify improvement areas.

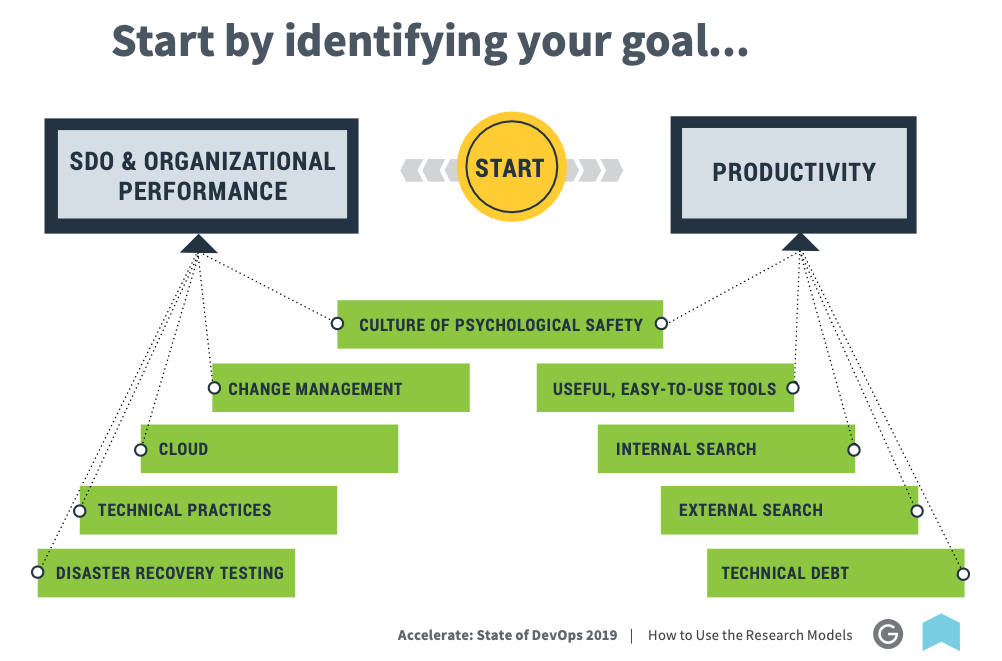

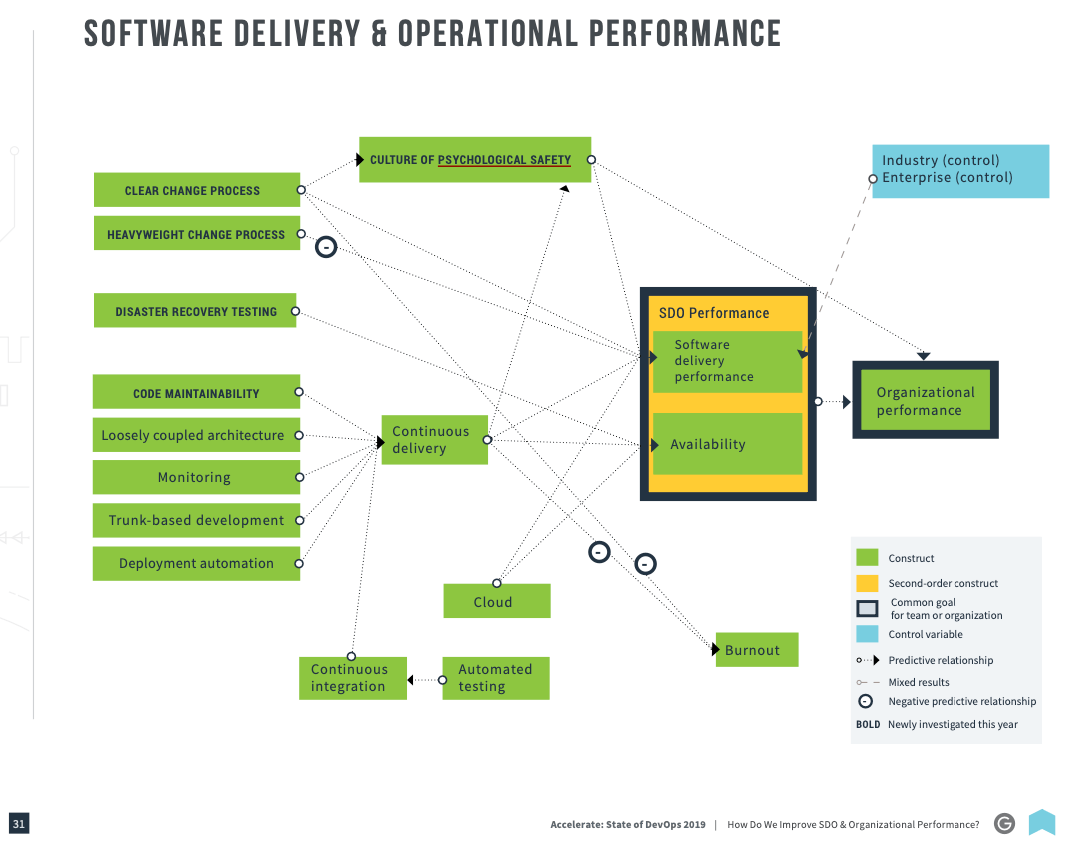

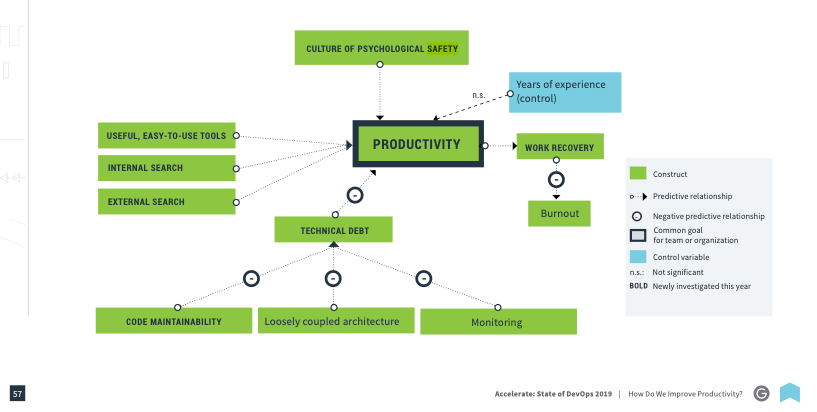

Research on psychological safety has been conclusive enough that in the 2019 DORA State of DevOps report it was prominently featured:

From the 2019 DORA State of DevOps

The report stated:

Our analysis found that this culture of psychological safety is predictive of software delivery performance, organizational performance, and productivity. Although Project Aristotle measured different outcomes, these results indicate that teams with a culture of trust and psychological safety, with meaningful work and clarity, see significant benefits outside of Google.

Given the importance of the findings, why are they still not the norm in most places?

It turns out that the central role of leaders and managers is a great opportunity but also a key challenge. Implementation in practice is an entirely different matter.

Challenges in implementation

Let’s examine the challenges leaders face at the team and organizational level.

Misconception of comfort

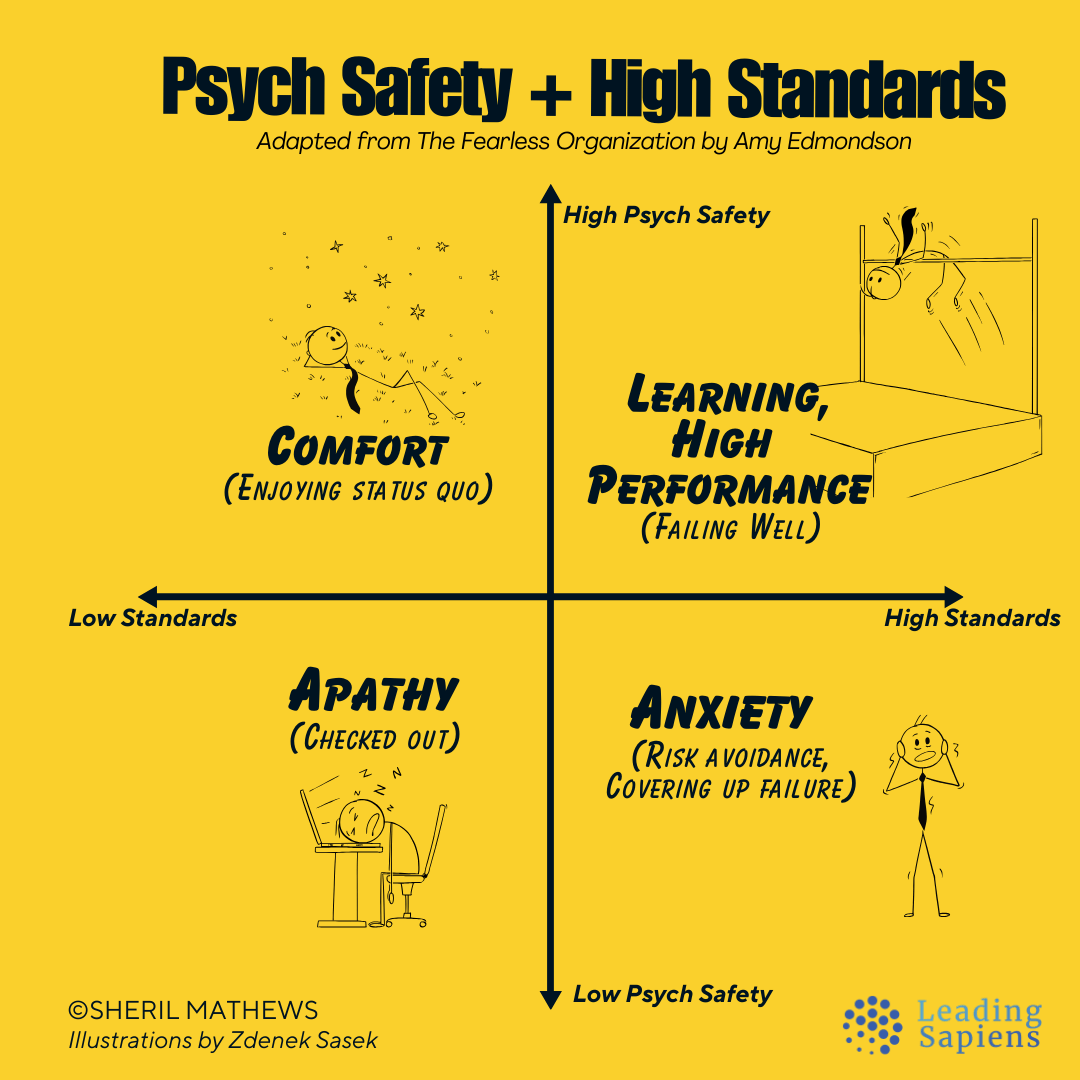

Many mistakenly assume that psychological safety means ensuring comfort, which breeds complacency. But it is not about eliminating discomfort; rather, it creates a space where productive discomfort—challenging ideas, debating, and exploring uncertainties—thrives without fear of punishment or judgment. Research shows that psychological safety has to be combined with a learning orientation to avoid a stagnant, overly safe environment.

Leaders struggle because it feels paradoxical to embrace discomfort while maintaining safety. They either prefer comfort or avoid conflict altogether.

They want clarity, decisiveness, and actionable ideas —qualities that don’t align with the messiness of open-ended dialogue. This stifles the constructive tension that leads to breakthroughs and instead focuses on creating superficial agreement.

Amy Edmondson put it this way:

Psychological safety is not an “anything goes” environment where people are not expected to adhere to high standards or meet deadlines. It is not about becoming “comfortable” at work.

This is particularly important to understand because many managers appreciate the appeal of error-reporting, help-seeking, and other proactive behavior to help their organizations learn. At the same time, they implicitly equate psychological safety with relaxing performance standards – that is, with an inability to, in their words, “hold people accountable.” This conveys a misunderstanding of the nature of the phenomenon.

Fear of conflict and time constraints make leaders default to control-oriented leadership styles instead of creating open, inclusive environments where everyone contributes. Edmondson’s research on learning from failure shows many teams hesitate to surface mistakes or challenge authority, even in supportive settings.

Siren call of talent

Most organizations still believe that assembling the best talent automatically results in high-performing teams. Managers prioritize resumes, past achievements, and technical skills as indicators of future success. Thus individual talent overshadows the subtler, harder-to-measure aspects of collaboration and norms.

Prioritizing norms over individual excellence is hard because it doesn’t align with how organizations are structured. Recruitment and performance evaluation processes prioritize individual capability, not collective behavior.

Norms are viewed as "soft" while talent seems more tangible and measurable. Managers believe that star performers drive success, while norms feel abstract and harder to quantify. Managing relationships, building trust, and ensuring equal participation are treated as secondary to hard metrics like technical skills or sales targets.

Challenge of constructive conflict

Another misconception about psychological safety is that it requires teams to always be harmonious. Leaders avoid conflict due to fears it will harm relationships or impede progress.

But healthy conflict is essential for innovation and growth. Psychological safety means dissent can happen without personal attacks. The best-performing teams engage in constructive disagreements and use it to channel conflict productively.

Leaders struggle because they must facilitate difficult conversations instead of resolving or avoiding them. Encouraging dissent doesn't mean creating negativity— it means allowing room for differing perspectives to challenge dominant views without fear of retribution.

Tightrope of flexibility

Leaders feel they must choose between being rigid taskmasters or overly flexible coaches. However, this is a false dichotomy — you need both. Without clarity and accountability, teams become directionless; without autonomy, they feel micromanaged.

Leaders must clearly define performance expectations while allowing flexibility in how teams achieve those goals. The key lies in creating a structure where dependability is reinforced as a shared team norm.

Mundanity of dependability

Dependability isn’t glamorous. We assume that high-performance teams are driven by innovation, creativity, and vision, but consistent execution is often the winning difference. Excellence is often mundane. It's the silent driver of success. The mistake is to focus on flashy initiatives while missing the importance of simply getting things done.

Dependability means not just setting deadlines but also norms of responsibility—where people hold each other accountable collaboratively rather than punitively. Leaders must assess and refine performance standards, ensuring expectations are transparent and achievable.

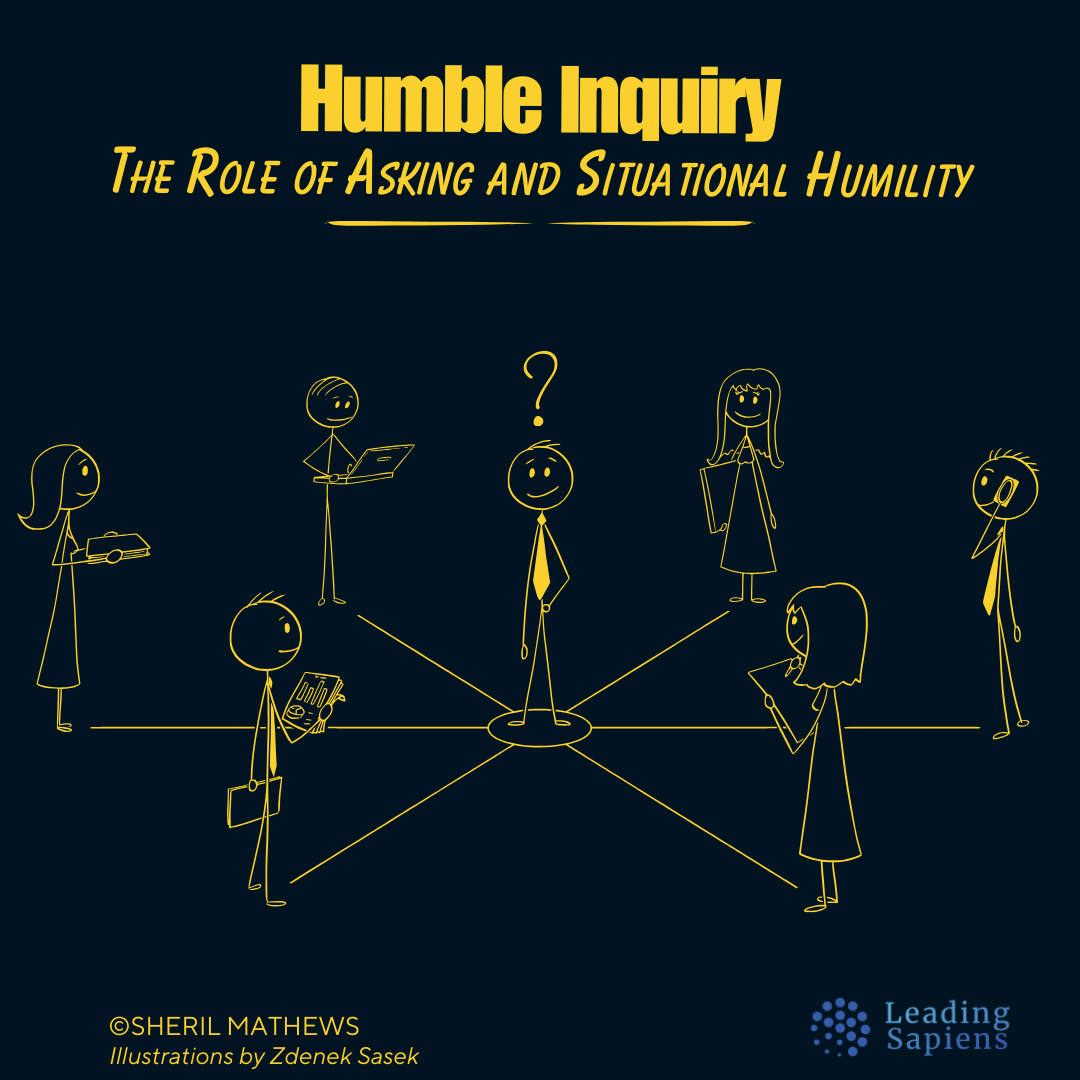

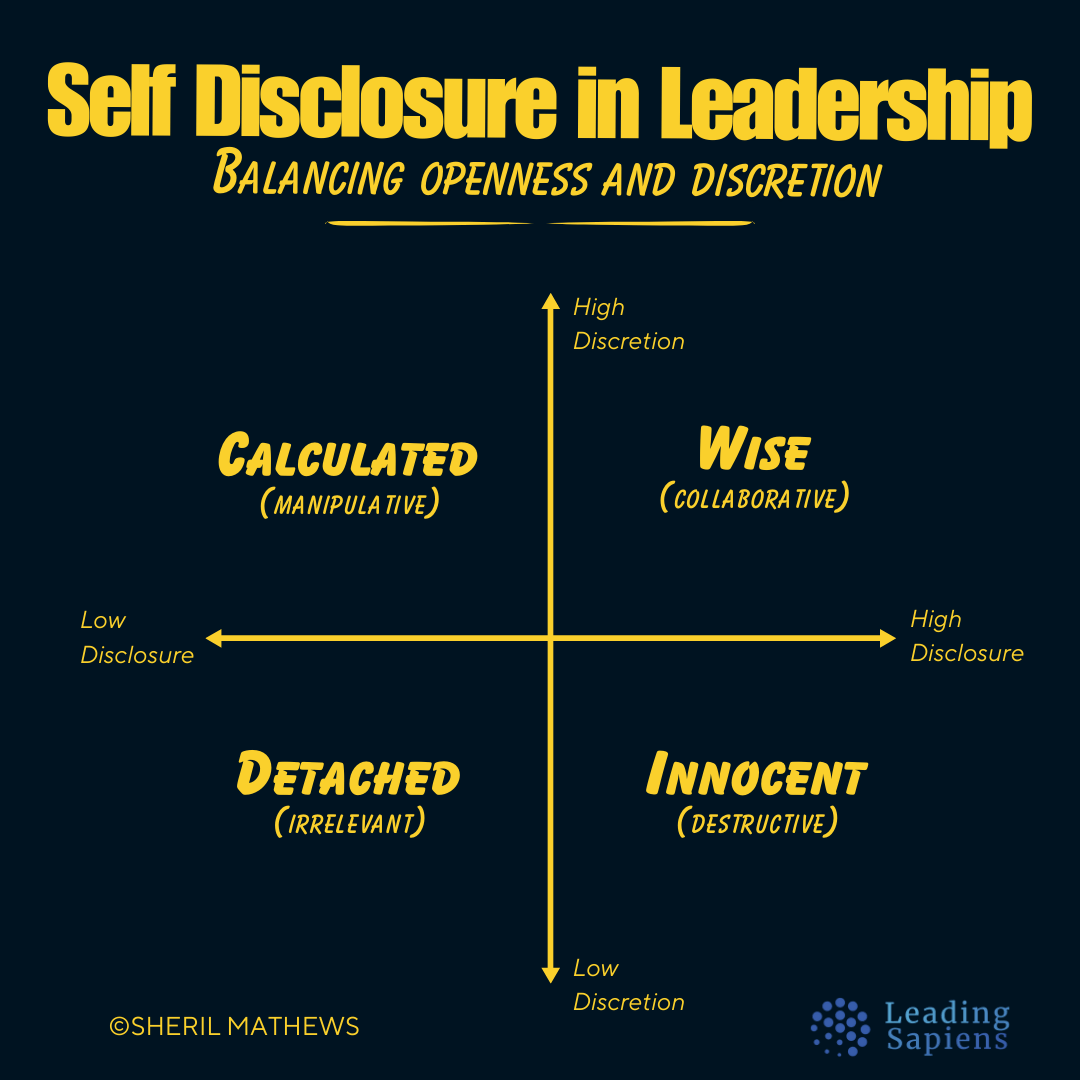

Myth of infallibility

Many leaders feel the need to project infallibility — the belief that they must always have the answers. Admitting uncertainty or a lack of knowledge can feel risky. However, Edmondson’s research shows that leaders who model vulnerability create a safe space for learning, where team members feel empowered to do the same.

This shift is hard because it requires unlearning traditional models of authority. The idea that vulnerability increases your effectiveness feels counterintuitive, especially in places that reward perfectionism and penalize mistakes.

A related idea is the Johari Window – where specific self-disclosure and seeking feedback increases your credibility.

Pressure of failure

The counterintuitive nature of the findings becomes more pronounced in high-risk, high-pressure environments like healthcare and aviation. Vulnerability and psychological safety feel risky—leaders mistakenly assume that fostering safety means lowering standards. But research from Edmondson’s work on the Columbia disaster shows that in high-risk settings, psychological safety allows teams to spot and address ambiguous threats before they escalate into disasters.

Psychological safety enhances accountability and performance standards instead of reducing them. It creates a cycle of continuous learning, where risks are openly discussed rather than hidden.

Underestimating commitment

Leaders underestimate the difficulty of cultivating a true learning culture. They must balance encouraging risk-taking and ensuring accountability—two seemingly contradictory concepts.

The nuance—that psychological safety alone isn’t enough—requires leaders to adopt an ongoing learning mindset, which is challenging to embed. It demands time, resources, and a shift away from traditional performance metrics.

Project Aristotle offers a clear framework for building high-performing teams, but implementing the findings in practice is fraught with challenges. Leaders must be intentional in creating psychological safety, balancing it with accountability, and ensuring alignment on goals and roles. You have to let go of outdated assumptions about talent and authority and actively shape team norms.

The real work lies in persistent practice — rituals, structures, and feedback loops that reinforce and enable the principles. Without it, you risk reverting to traditional modes of management, leading to a “same-old-same-old” dysfunctional culture.

Related Reading on Psychological Safety

Sources

- Re:Work by Google

- Edmondson, A. C., Roberto, M. A., Bohmer, R. M., Ferlins, E., & Feldman, L. R. The Recovery Window: Organizational Learning Following Ambiguous Threats.

- Edmondson, A. C. The Fearless Organization.

- Sanner, B., & Bunderson, J. S. “When Feeling Safe Isn’t Enough: Contextualizing Models of Safety and Learning in Teams.”

- 2019, 2023 State of DevOps Report. DORA.

- Edmondson, A. C. “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams.”

- Bohmer, R., Edmondson, A. C., & Roberto, M. A. “Facing Ambiguous Threats.” Harvard Business Review.

- Hackman, J. R. Leading Teams.

- Duhigg, C. "What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team."

- Blomstrom, D. People Before Tech.