The term “psychological safety” is often misleading. When managers hear safety, many dismiss it as a soft style that implies complacency. Meanwhile, psychology implies too much mumbo jumbo. High-profile figures like Elon Musk advocating for a “hardcore” style perpetuate this misconception. But this is a fundamental misunderstanding of the relationship between high standards and psychological safety.

In this piece, I unpack the confusion surrounding psychological safety and why you need both psychological safety and high standards to achieve high performance.

In his biography of Elon Musk, Walter Isaacson cites an exchange that’s telling. The backdrop is the initial days after Musk took over Twitter.

Between Twitterland and the Muskverse was a radical divergence in outlook that reflected two different mindsets about the American workplace. Twitter prided itself on being a friendly place where coddling was considered a virtue. “We were definitely very high-empathy, very caring about inclusion and diversity; everyone needs to feel safe here,” says Leslie Berland, who was chief marketing and people officer until she was fired by Musk. The company had instituted a permanent work-from-home option and allowed a mental “day of rest” each month. One of the commonly used buzzwords at the company was “psychological safety.” Care was taken not to discomfort.

Musk let loose a bitter laugh when he heard the phrase “psychological safety.” It made him recoil. He considered it to be the enemy of urgency, progress, orbital velocity. His preferred buzzword was “hardcore.” Discomfort, he believed, was a good thing. It was a weapon against the scourge of complacency. Vacations, flower-smelling, work-life balance, and days of “mental rest” were not his thing. Let that sink in.

…

Musk had wrought one of the greatest shifts in corporate culture ever. Twitter had gone from being among the most nurturing workplaces, replete with free artisanal meals and yoga studios and paid rest days and concern for “psychological safety,” to the other extreme. He did it not only for cost reasons. He preferred a scrappy, hard-driven environment where rabid warriors felt psychological danger rather than comfort. [1]

Amy Edmondson of Harvard, the leading researcher in psychological safety, defines it as the belief that you won't be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes. It encourages intelligent risk-taking by reducing interpersonal anxiety.

Hundreds of studies, including Google’s Project Aristotle, show that psychological safety is essential for high performance in the modern workplace. Given its importance, you’d think managers would actively work to enable it.

Yet, in practice, these findings often fall on deaf ears. Why is this so?

In my experience, there are two main confusions that muddle the message: “comfort” and “safe spaces.” Let’s examine the two.

Psychological safety is not “comfort”

In Isaacson’s exchange, psychological safety is conflated with “coddling” and “not to discomfort”. Meanwhile, “hardcore” is considered the opposite. The implied message? "Psych safety is for losers; we are hardcore here".

Musk's disdain for the term "safety" stems from its association with a lack of urgency, complacency, and laziness. For him, discomfort drives productivity, where fear and stress combat complacency and push people toward "orbital velocity."

From his perspective, psychological safety is the opposite of high performance. It hinders accountability and the "hardcore" mindset required for rapid innovation. Comfort is anathema to performance, and psychological safety is about free artisanal meals and a lax work attitude.

Musk isn’t alone in making this mistake. As a manager, when I myself came across the concept in 2018 I dismissed it as “soft” and another management fad destined to die.

Edmondson herself acknowledges the problem with terminology:

The term implies to people a sense of coziness — “Oh, everything’s going to be great” — and that we’re all going to be nice to each other. That’s not what it’s really about. It’s about candor, about being direct, taking risks, and being willing to say, “I screwed that up.” It’s being willing to ask for help when you’re in over your head. [2]

Maybe that’s why she called her 2018 book “Fearless Organization” instead of “The Psychologically Safe Organization.”

She clarifies:

Psychological safety is not an “anything goes” environment where people are not expected to adhere to high standards or meet deadlines. It is not about becoming “comfortable” at work.

This is particularly important to understand because many managers appreciate the appeal of error-reporting, help-seeking, and other proactive behavior to help their organizations learn. At the same time, they implicitly equate psychological safety with relaxing performance standards – that is, with an inability to, in their words, “hold people accountable.” This conveys a misunderstanding of the nature of the phenomenon. [4]

Such a climate does not, however, deny failure and whitewash poor results but examines them to see how they can be eliminated or reduced. The reinforcement that comes initially from others and later from oneself is the knowledge that one has made a genuine attempt and that failure occurred only because one's goals were beyond one's current abilities. Failure to perform beyond one's limits is not the same as failure to perform what one is capable of performing.

— Chris Argyris, Donald Schon, Theory in Practice

Let’s look at the next culprit.

It’s not about “safe spaces” either

Another term that adds to the confusion is 'safe spaces.' Although sounding similar, they serve different purposes and come from different contexts. Even experienced practitioners get these two mixed up.

Safe spaces originated in social movements and are designed to be environments free of conflict. They're found in educational settings or communities dealing with sensitive issues, where the goal is to protect individuals from potentially harmful situations. Discomfort is intentionally minimized, and clear boundaries are set from the outset.

Meanwhile, psychological safety emerged in the context of organizations and team dynamics. It focuses on creating environments where people feel safe to speak up, make mistakes, and take risks, especially in challenging, high-stakes situations.

Unlike safe spaces, psychological safety doesn't aim to eliminate discomfort. Instead, it ensures discomfort is productive — an essential part of learning and growth.

Safe spaces are about protection from external judgment by removing threats or negative stimuli. In contrast, psychological safety encourages risk-taking for group performance and learning.

This distinction is crucial. Equating psychological safety with safe spaces creates the misconception that it means avoiding accountability or difficult feedback. In reality, it is compatible with high standards and challenging expectations.

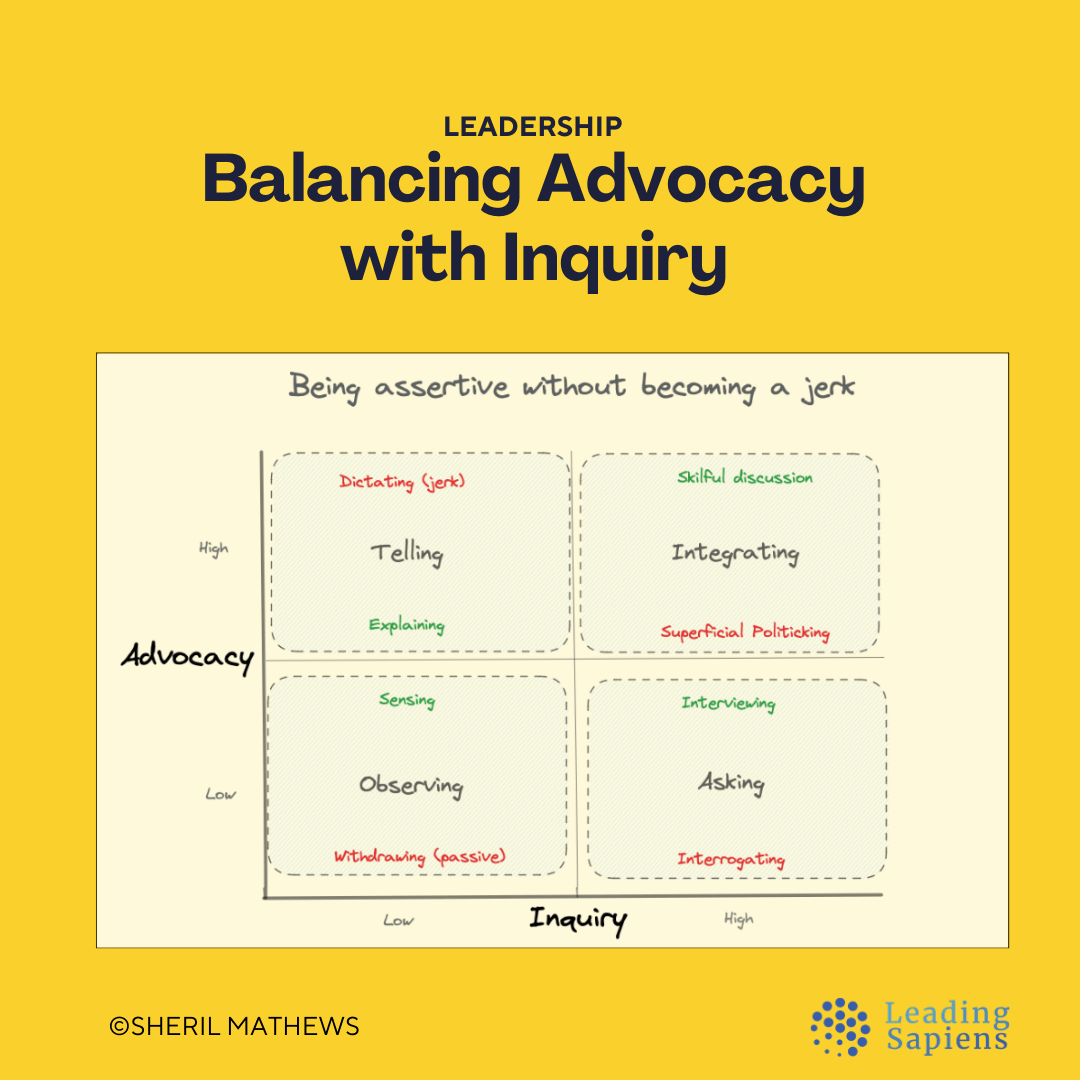

The role of leadership also differs. In safe spaces, leaders act as guardians, setting and enforcing norms to protect members. In psychologically safe workplaces, they model fallibility, ensure open dialogue, practice humble inquiry, and frame failures as learning opportunities.

A psychologically safe workplace isn't devoid of challenge or discomfort; it ensures that discomfort is generative, not destructive.

What Psychological Safety really is

Psychological safety isn't about avoiding discomfort; it's about ensuring that discomfort — what Musk calls "hardcore"— fosters growth, intelligent risk-taking, and learning. He is half-right: there's no growth without discomfort. But for people to embrace it productively, you need psychological safety. This means creating an environment where people feel secure enough to fully engage, experiment, make mistakes, and challenge themselves and their leaders.

Contrary to misconceptions, psychological safety enables — not hinders — the "discomfort" and "hardcore" approach that Musk advocates. It's not about removing accountability or avoiding challenges, but supporting people to confidently face them head-on.

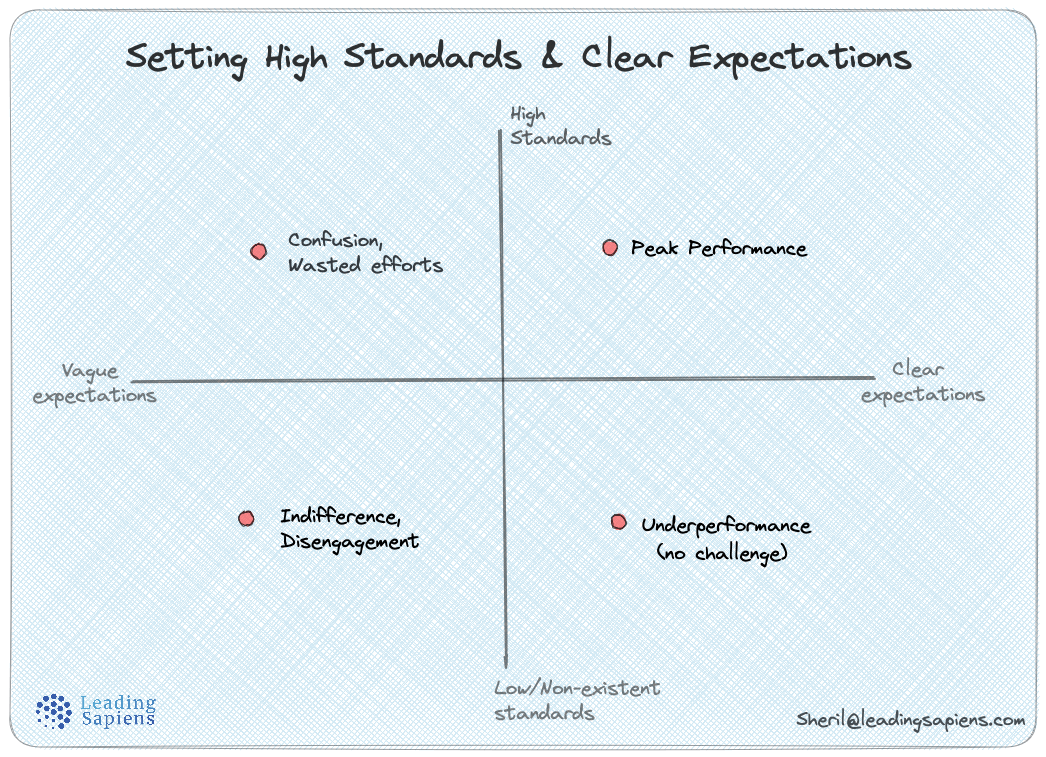

To use one of Edmondson's analogies: psychological safety is like removing the brakes that keep a car from moving, while high standards act as the steering mechanism. Without it, even with high standards, you risk chaos—team members may be too afraid to accelerate, or if they do, they might crash due to uncertainty.

While discomfort is indeed a powerful catalyst, it's an error to assume stress and fear are the only ways to generate urgency. High standards are most effective when people feel supported in reaching them. Without psychological safety, innovation suffers as people avoid exposing their vulnerabilities or lack of skills, fearing ridicule and punishment.

High-performance teams understand that excellence requires iterative failures. They don't demand perfection; instead, they encourage trial, error, and adjustment. In this environment, failure isn't just tolerated; it's an integral part of the process.

Expectations remain high, and people work hard. However, the crucial difference is that it's safe to fail and learn, driving both individual and organizational growth.

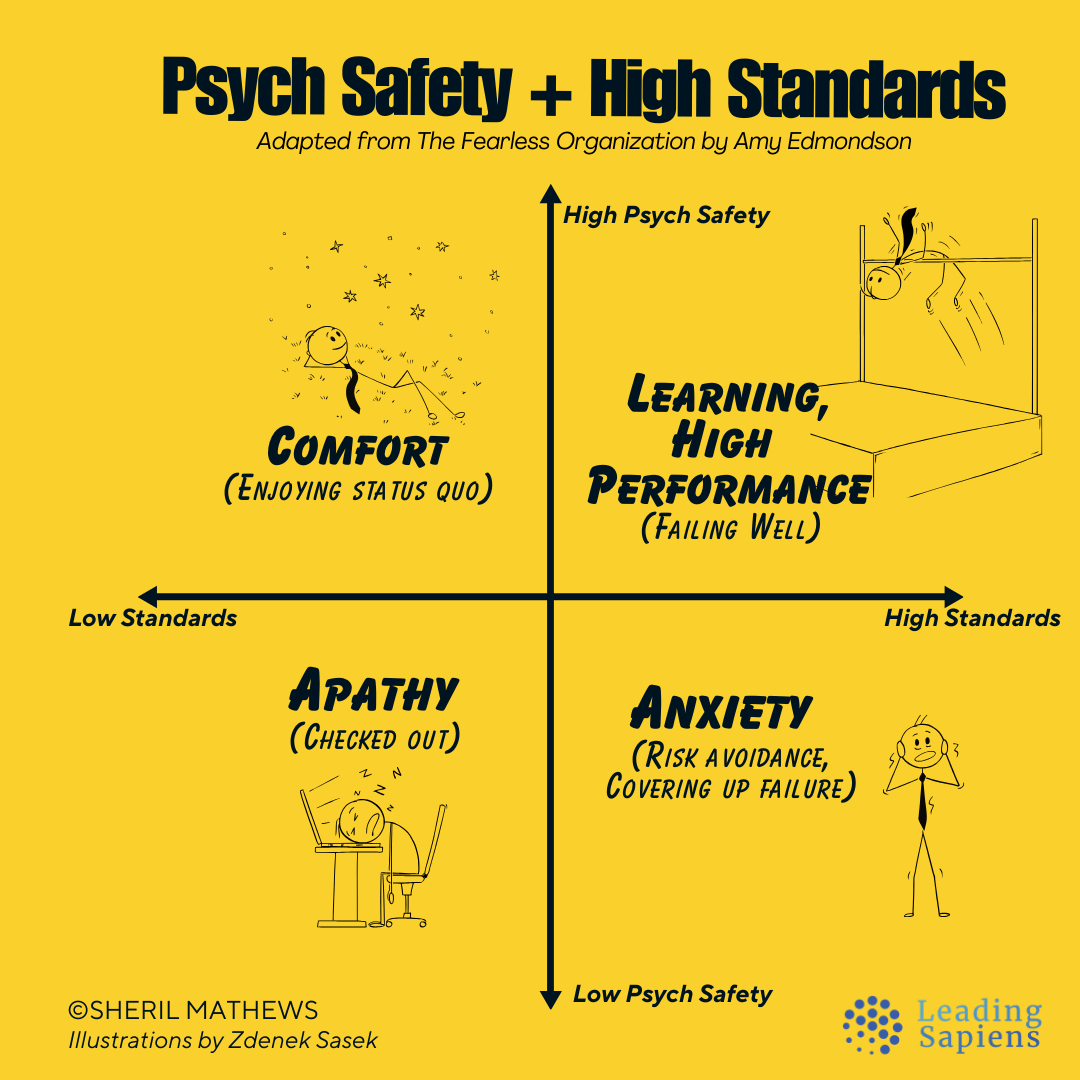

The 4 organizational archetypes

Elon Musk's management of Twitter is an extreme example of coercive power. He let go 75% of the workforce to ensure only the "hardcore" survived. The idea was that discomfort would push the remaining employees to innovate and execute faster, which, to some extent, did happen. Twitter continued to operate, albeit in a diminished form, and introduced new features with a much smaller staff.

High pressure and discomfort can indeed lead to bursts of productivity, especially in a crisis where the stakes are high and the need for immediate action is clear. However, sustained pressure without psychological safety leads to burnout, reduced creativity, and reluctance to take risks. People focus on avoiding failure rather than striving for excellence. This anxiety undermines the creativity that companies like Twitter need to thrive.

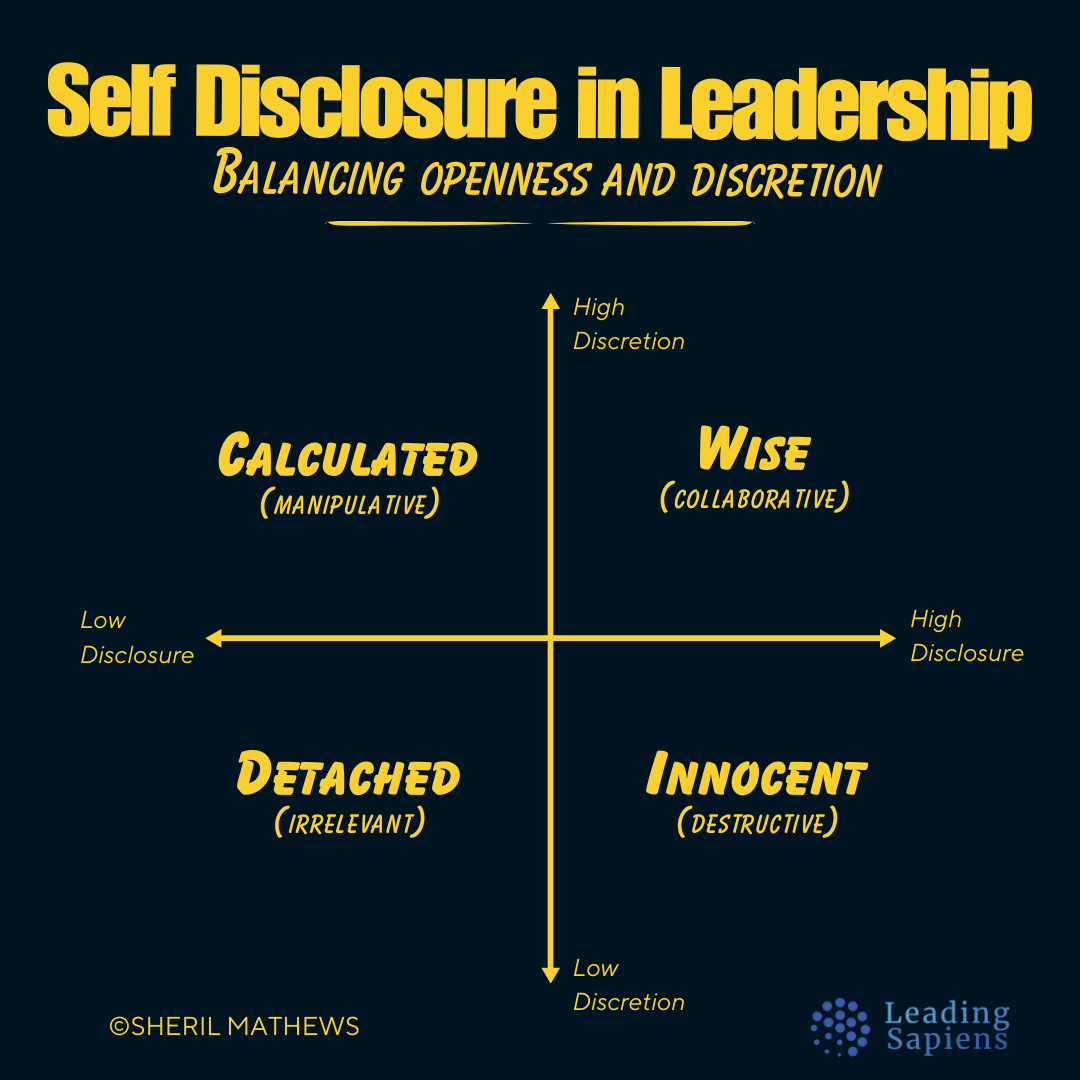

This interplay between high standards and psychological safety is depicted by Edmondson’s 4 organizational archetypes:

High Safety, Low Standards (Comfort Zone)

This is the version of psychological safety Musk imagined — one where no one is pushed to excel. Teams enjoy a collegial atmosphere and are comfortable but lack challenge.

While this might seem pleasant on the surface, it's not conducive to learning, innovation, or high engagement. Without a compelling reason to push boundaries, teams don't grow or achieve significant results.

It’s a breeding ground for complacency. There’s a lack of healthy conflict or debate, with people agreeing too readily to maintain the status quo. Without a pressing need to improve or take risks, innovation stagnates. The desire for harmony overrides critical thinking, leading to groupthink. This results in a decline in competitive edge and market relevance.

Low Safety, High Standards (Anxiety Zone)

This quadrant epitomizes Musk's "hardcore" management. It's a common pitfall in modern workplaces, where leaders demand excellence but fail to cultivate psychological safety. The result is an anxiety-inducing environment that undermines the very performance it seeks to enhance.

There’s often a veneer of productivity masking deeper issues. Teams may seem to be highly productive, but there's increasing signs of burnout – absenteeism, declining work quality, and a blame culture. Information is hoarded for job security instead of shared for collective benefit.

Teams retreat to the status quo, paralyzed by the fear of failure. Crucial questions remain unvoiced, stifling quality and ingenuity. The organization inadvertently cultivates a risk-averse workforce, favoring "safe" decisions over potentially transformative ones.

People work hard, but primarily out of fear. While it may yield short-term results, it limits an organization's capacity for breakthroughs and sustained growth.

High Safety, High Standards (Learning Zone)

This is the sweet spot where psychological safety and high standards coexist. In this quadrant, people feel empowered to take calculated risks, voice unconventional ideas, and own up to mistakes without fear of repercussions.

It balances both comfort and challenge. Ideas are challenged respectfully, regardless of the source. Feedback flows freely and constructively in all directions, regardless of hierarchy. Teams feel secure enough to push boundaries and tackle complex problems, knowing they have support.

Failures aren't career-ending; they're viewed as learning opportunities. Cross-functional collaboration happens organically, as people seek diverse viewpoints to solve problems. Innovation thrives because people feel safe to experiment. They're not paralyzed by fear of failure but energized by the possibility of breakthrough. This creates a dynamic, engaged workforce pushing the envelope.

Low Safety, Low Standards (Apathy Zone)

Without safety or standards, people do the bare minimum to stay employed. Team members may engage in “presenteeism” or “quiet quitting” - showing up physically but not mentally. They likely prioritize self-protection over extra effort, leading to unproductive behaviors and conflicts. This is common in large, bureaucratic organizations where people have figured out how to do their jobs with minimal effort.

In these places, mediocrity takes root along with passive-aggressive behavior, office politics, and a lack of initiative. There’s also high turnover rates and strong resistance to change.

People develop learned helplessness, believing their efforts won't matter. It creates a destructive cycle where low expectations lead to low performance, reinforcing apathy.

The paradox of “hard” and “soft”

Psychological safety and accountability are not two ends of a continuum, but rather two distinct attributes of a work environment. [3]

The dichotomy of either psychological safety or high standards is a classic case of “either/or” thinking. Effective leadership requires an “and” approach: integrating both psychological safety and high standards to create places where people can take risks and be challenged simultaneously.

A culture that makes it safe to talk about failure can coexist with high standards… This is as true in families as it is at work. Psychological safety isn’t synonymous with “anything goes.”

A workplace can be psychologically safe and still expect people to do excellent work or meet deadlines. A family can be psychologically safe and still expect everyone to wash dishes and take out the trash. It’s possible to create an environment where candor and openness seem feasible: an honest, challenging, collaborative environment. I’d go so far as to say that insisting on high standards without psychological safety is a recipe for failure— and not the good kind. [5]

Psychological safety and high standards are complementary, not contradictory. The job of leadership is to both challenge and support. It allows people to fully commit to high standards because they trust they won't be penalized for mistakes or deviations during the learning process.

Jim Collins calls this leadership dynamic “the paradox of hard and soft”:

A good leader doesn’t demand high performance (demanding implies that people are basically lazy and are inclined to withhold their best effort—that it must be extracted out of them, like pulling teeth). No, a good leader offers people the opportunity to test themselves, to grow, and to do their best work.

There is no shortage of people interested in doing something in which they can take pride. But there is a vast shortage of leaders who provide the stimulation of stiff challenge and high standards, combined with the uncompromising belief that seemingly ordinary people can do extraordinary things.

…

Leaders who build great companies master the paradox of hard and soft. They hold people to incredibly high standards of performance (hard) yet they go to great lengths to build people up—to make them feel good about themselves and about what they are capable of achieving (soft). [6]

As leaders, the challenge is to create an environment for team members feel secure enough while pushing to meet ambitious goals. It's not about implementing policies, but about modeling and reinforcing behaviors that support both safety and excellence.

Pay attention to subtle indicators. Are team members engaging in candid discussions about failures? Do they proactively seek feedback? These signs can help you gauge if you're in a "Learning Zone" or "Anxiety Zone".

The goal isn't to eliminate discomfort, but to ensure it serves a productive purpose. Mastering this balance sets the stage for excellence.

Further reading

Sources

- Isaacson, W. (2023). Elon Musk.

- Edmondson, A. C. (2024). Interview. In Harvard Business Review, Psychological Safety (Emotional Intelligence Series).

- Edmondson, A. C. (2012). Teaming.

- Edmondson, A. C. (2018). The Fearless Organization.

- Edmondson, A. C. (2023). Right Kind of Wrong.

- Collins, J. (2020). Beyond Entrepreneurship 2.0.

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. A. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness.

- Duhigg, C. (2016). What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team.

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological Safety: The History, Renaissance, and Future of an Interpersonal Construct.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams.