In conventional leadership, competence is about maintaining composure, projecting strength, and exuding confidence. However, truly effective leaders do something more surprising: self-disclosure. They share their fallibility as well as strengths.

Self-disclosure is a misunderstood skill of effective leadership. How much is too much? And how can you ensure that opening up doesn’t undermine your authority? In this piece, I explore self-disclosure’s role in leadership, common mistakes to avoid, and using it appropriately.

“The most dangerous leadership myth is that leaders are born,” quipped leadership guru Warren Bennis. An equally dangerous myth is that they must always appear infallible.

In my 25+ years in corporate America, I’ve seen countless “perfect” presentations and flawless strategies. Yet, the most impactful moment was when a senior leader candidly shared her professional failure with the team. Whether she knew it or not, she was leveraging the art of self-disclosure.

Consider a more dramatic example under more intense circumstances.

In the brutal confines of the "Hanoi Hilton," Admiral James Stockdale faced an unprecedented leadership challenge. Captured in 1965 during the Vietnam War, he was the senior naval officer among the prisoners of war. Rather than project an image of invulnerability, Stockdale made a counterintuitive choice: he openly shared his pain, fears, and struggles with fellow inmates.

By disclosing his vulnerability, he created a bond of trust and resilience among the POWs. He discussed the tortures he endured, moments of despair, and strategies for maintaining hope. This encouraged others to share their experiences, creating a support network that proved crucial for survival.

Stockdale's counter-intuitive approach to leadership — later dubbed the "Stockdale Paradox" — helped maintain morale and unity among the prisoners for over seven years. His strategic self-disclosure in the most challenging circumstances is a powerful lesson for leaders: showing fallibility can sometimes be the strongest form of leadership.

What is self-disclosure

Self-disclosure is about sharing your thoughts, experiences, and vulnerabilities to others. In leadership, it’s about selectively sharing aspects to create connection, build trust, and ultimately enhance relationships.

It’s not about transparency or oversharing every personal detail; it’s finding the right balance — being open enough to be relatable and trustworthy while maintaining the discretion and awareness necessary for leadership.

Reed Hastings, co-founder and chairman of Netflix, put it this way:

Every time I feel I’ve made a mistake, I talk about it fully, publicly, and frequently. I quickly came to see the biggest advantage of sunshining a leader’s errors is to encourage everyone to think of making mistakes as normal. This in turn encourages employees to take risks when success is uncertain . . . which leads to greater innovation across the company. Self-disclosure builds trust, seeking help boosts learning, admitting mistakes fosters forgiveness, and broadcasting failures encourages your people to act courageously.

…Humility is important in a leader and role model. When you succeed, speak about it softly or let others mention it for you. But when you make a mistake say it clearly and loudly, so that everyone can learn and profit from your errors. In other words, “Whisper wins and shout mistakes.” [2]

Appropriate self-disclosure in leadership transforms relationships from transactional to meaningful.

The key is balancing openness with discretion, considering timing and context. The hidden quadrant of the Johari Window — a framework for understanding aspects of ourselves known only to us — can help in this assessment.

Self-disclosure isn’t an isolated act. It’s a back-and-forth process of sharing information and inviting connection. This reciprocity builds trust, deepens relationships, and enhances both individual and collective effectiveness.

Inauthenticity and lack of self-disclosure

Authenticity has become a buzzword in leadership, yet many struggle to embody it genuinely. This begs the question: Why do leaders come across as inauthentic?

One reason is our tendency to protect ourselves. We fear vulnerability, believing that showing our true selves will lead to exploitation or loss of respect.

I see this pattern often in my coaching practice. There are two typical types of leaders.

First are the infallible exemplars. Many leaders believe they can't be authentic at work. They construct a persona of unwavering competence and confidence, rigidly separating their professional and personal lives. The focus is on sophistication and avoiding looking naive or incompetent.

With newer leaders, this might mean adhering strictly to scripted responses. For experienced ones, it manifests as an impenetrable facade of minimal self-disclosure.

The result is that they are too focused on “seeming like” rather than “being” leaders. The constant guardedness takes a significant emotional and energy toll because maintaining a facade is exhausting.

The second type is the overzealous truth-teller. Although less common, it is equally problematic because they lack filters, sharing indiscriminately without consideration for timing or context. In a misguided attempt at transparency and authenticity, these leaders fail to recognize the importance of boundaries and context in leadership communication. While presumably easier on the leader, it has a harmful effect on teams and how others perceive them.

Both extremes stem from a misunderstanding of what true authenticity in leadership entails.

The antidote lies in mastering appropriate self-disclosure. True authenticity isn't about being an open book. Effective leaders navigate the middle ground, sharing authentically but judiciously. They know when, how, and what to disclose to build trust and create a culture of openness without compromising effectiveness.

What role does self-disclosure play in effective leadership, and how can you strike the right balance?

The role of self-disclosure in leadership

The most impactful self-disclosure often isn’t you, but instead creating space for others. It affects many aspects of leadership and acts as a catalyst for effectiveness. Let’s examine some crucial ones.

1. Building trust and openness

Self-disclosure increases your perceived competence. It builds trust, the foundation of effective leadership. By revealing vulnerabilities, leaders show they are not infallible, encouraging team members to open up and creating a cycle of transparency that strengthens cohesion.

Vulnerability doesn’t diminish authority; it humanizes leaders, making them more relatable and approachable. It creates an environment where team members feel safe and voice concerns.

Self-disclosure breaks down hierarchical barriers. Sharing challenges signals that you value authenticity over rigid authority, creating a more collaborative dynamic.

2. Normalizing mistakes creates psychological safety

Self-disclosure is crucial for creating psychological safety, a key driver of high-performing teams as seen in Google's Project Aristotle. It's the belief that you can speak up, admit mistakes, and voice concerns without fear of punishment or ridicule. Leaders who disclose their limitations or ask for help show it’s acceptable to not have all the answers.

Admitting mistakes openly and sincerely alters team dynamics. It reinforces that no one is infallible and that it's a normal part of growth. This transparency reduces the stigma around failure.

3. Modeling growth mindset

Self-disclosure models behavior that enables a growth mindset. It encourages teams to view failures not as a reflection of inadequacy but as an opportunity for learning and improvement.

Strategic self-disclosure influences others’ perception of your leadership presence. It shifts you from a one-dimensional, authoritative figure to a human leader who is genuine, thoughtful, and evolving. It signals that openness isn’t weakness but a necessary ingredient for growth and collaboration.

4. Fostering reciprocity and connection

Another significant aspect is the reciprocity of self-disclosure. It’s not a one-way process. When you open up, it triggers an exchange where people are more inclined to share their own stories, concerns, and insights. This reciprocal disclosure strengthens bonds and increases relational depth.

Self-disclosure creates not just comfort, but also productive tension. It acts as a bridge, closing the emotional and psychological distance that exists between leaders and their teams.

Common mistakes in self-disclosure

Given its importance, many leaders try to leverage self-disclosure but end up causing more harm than good. Here are common stumbling blocks I’ve seen and how to avoid them.

1. Oversharing or undersharing

While self-disclosure is powerful, it must be approached carefully. A common pitfall is overdoing it.

Leaders who share too much, too soon, or too often come across as needy and lacking professional boundaries, making others uncomfortable. If you constantly share personal struggles you can be perceived as overwhelmed or incapable. This dilutes your authority and undermines your ability to lead decisively and inspire confidence.

In contrast, those who disclose too little appear cold, distant, and unapproachable. They create a barrier to connection and make it harder for people to trust them or feel comfortable. Withholding hinders authentic connections.

Striking the right balance is essential. Leaders should be mindful of how much they reveal, to whom, and in what context. The amount and depth of disclosure should suit the situation and audience.

2. Inconsistent disclosure

Another pitfall is inconsistency. You disclose vulnerabilities in one situation but remain closed off or defensive in others sending mixed messages, eroding trust and creating uncertainty. Consistency is crucial for effective self-disclosure. It must be genuine and sustained for any lasting impact.

3. Forced disclosure

Many fall into the trap of forcing or feigning self-disclosure. They do this through contrived team-building exercises or by demanding openness before establishing trust. Leaders who send their teams on mandatory retreats and expect deep revelations without first modeling vulnerability will find that people are reluctant to share. Forced disclosures feel inauthentic and backfire.

The worst form is fabrication and inauthenticity. When leaders fabricate stories or try to present themselves in a better light, they risk being seen as disingenuous. Once detected, this leads to a complete breakdown of trust, as it contradicts the authenticity that effective self-disclosure seeks to establish.

4. Misjudging context

Another mistake is failing to understand the cultural context of self-disclosure. Sharing personal vulnerabilities that resonate in one culture can backfire in another.

In some cultures, leaders must maintain composure and avoid discussing personal shortcomings, as such admissions can undermine perceived competence. Misjudging these norms leads to negative outcomes and erodes the respect necessary for effective leadership.

A diagnostic for self-disclosure

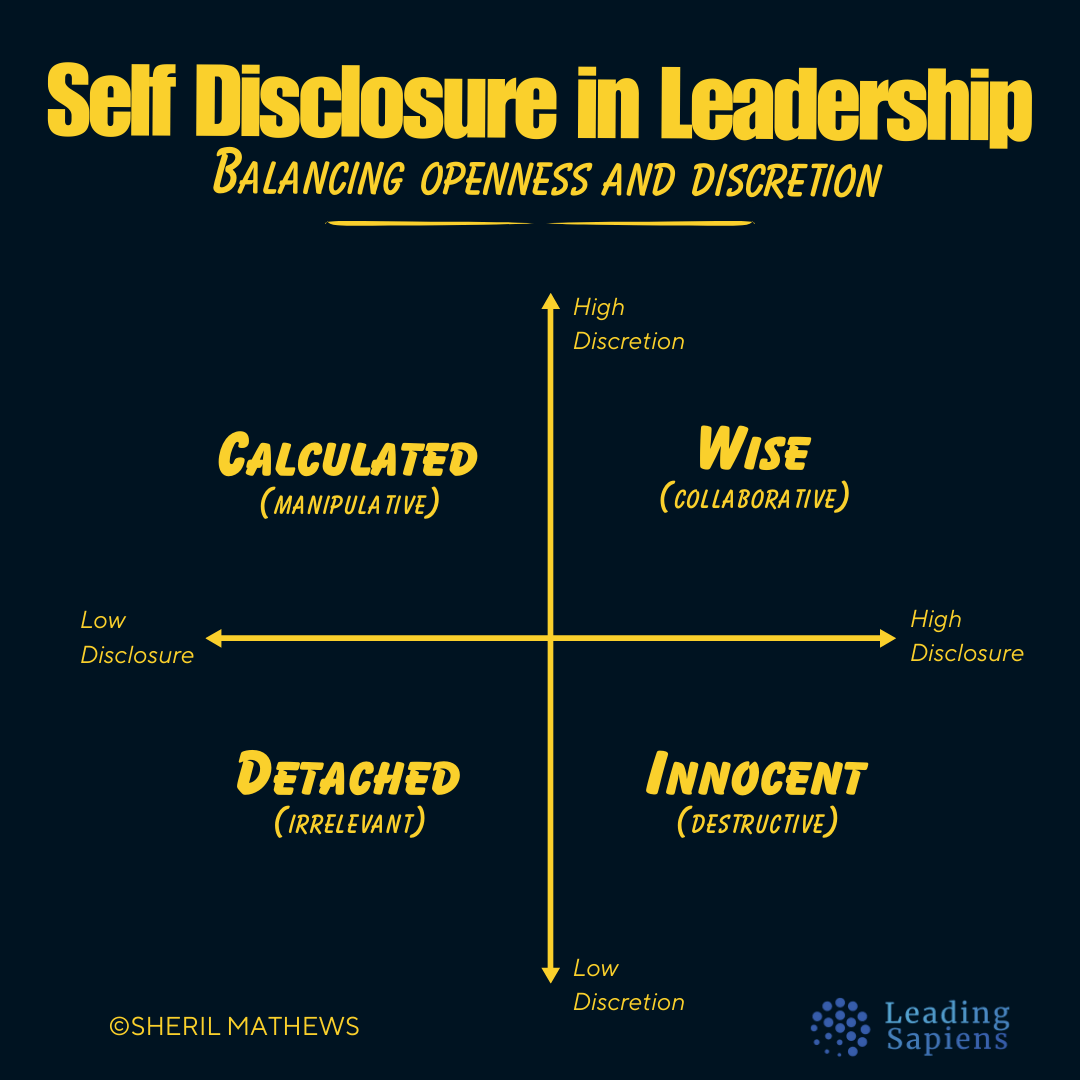

To further understand the balance of self-disclosure and discretion, visualize this dynamic as a 2X2 matrix of 'disclosure' and 'discretion.'

This creates four quadrants:

- WISE (high disclosure, high discretion): In this quadrant, leaders reveal personal insights and weaknesses thoughtfully and selectively. This balance creates deep connections and trust while maintaining authority.

- INNOCENT (high disclosure, low discretion): Leaders in this quadrant share openly without sufficient filters. This leads to loss of authority and makes others uncomfortable due to a lack of context or timing.

- DETACHED (low disclosure, low discretion): Leaders here are reluctant to share, and when they do, it lacks relevance or consideration. This creates detachment, making it difficult to build trust.

- CALCULATED(low disclosure, high discretion): Leaders in this quadrant are cautious and share very little. They maintain control, but this limits the depth of relationships, hindering genuine connection.

Where do you lie on this matrix and how can you move towards strategic sharing?

Practicing self-disclosure

Given the challenges of balancing disclosure and discretion, use these nine questions to reflect on and guide your practice of self-disclosure.

Do you have to use the questions each time? No. As with any skill, with practice it will become second nature.

- What's my intention for disclosure? How does it align with my leadership goals and the current context?

- Is the timing right, and will disclosure resonate with the current situation and shared understanding?

- How will disclosure impact team dynamics and meet my team's leadership needs?

- Am I building trust incrementally and encouraging reciprocity in my communication?

- Can the receiver understand and validate what I'm sharing, ensuring clear communication?

- Is the information level appropriate for my role? Have I considered the cultural and organizational context?

- Does my disclosure balance vulnerability and authority? Is it a reasonable and manageable risk?

- What have I learned from past disclosures, and how can I apply those lessons to this situation?

- Is increased transparency necessary during this current crisis or conflict?

These questions help you navigate the complexities of self-disclosure, ensuring openness is genuine and effective in enhancing your leadership presence.

Wrapping up

Self-disclosure requires finesse. When done well, it builds trust, creates deeper relationships, and a culture of psychological safety. However, it requires careful discernment.

Reflecting on your own leadership journey, consider where you fall on the self-disclosure spectrum. How might shifts in your approach to self-disclosure transform your effectiveness and team culture?

The goal is not perfection, but progress. Like Admiral Stockdale in his darkest hours, your willingness to be strategically vulnerable can unlock resilience in yourself and those you lead.

Sources

- Bennis, W. (1989). On Becoming a Leader.

- Hastings, R. (2020). No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention.

- Goffee, R., & Jones, G. (2006). Why Should Anyone Be Led by You?: What It Takes To Be An Authentic Leader.

- Rosh, L., & Offermann, L. (2013). Be Yourself, But Carefully. Harvard Business Review.

- Luft, J. (1969). Of Human Interaction.

- Edmondson, A. (2018). The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth.

- Stockdale, J. B. (1993). Courage Under Fire: Testing Epictetus's Doctrines in a Laboratory of Human Behavior.