Setting high standards is a well-understood, well-worn leadership strategy. Aiming for ambitious targets is also one area of goal-setting research that’s been conclusively proven across multiple studies.

But they are only one part of the equation. There is an equally important part that often gets left out. Jeff Bezos captured this key idea in his 2017 Amazon shareholder letter.

One of Amazon’s leadership principles is of setting high standards. [1]

Insist on the Highest Standards

Leaders have relentlessly high standards— many people may think these standards are unreasonably high. Leaders are continually raising the bar and drive their teams to deliver high quality products, services and processes. Leaders ensure that defects do not get sent down the line and that problems are fixed so they stay fixed.

- from Amazon's leadership principles

Statements like these are common and often sound cliched and banal. What's not common is an articulate elaboration, based on real experience, on how exactly to go about doing this.

In his 2017 letter to shareholders, Jeff Bezos did just that. He wrote a particularly insightful and equally practical memo elaborating this leadership principle. [2,3]

He highlights four critical aspects leaders have to pay attention to if they want to create a culture of high standards.

The four elements of high standards as we see it:

they are teachable, they are domain specific, you must recognize them, and you must explicitly coach realistic scope.

Let’s look at each of these, not necessarily in that order.

The effectiveness of high standards and challenging targets

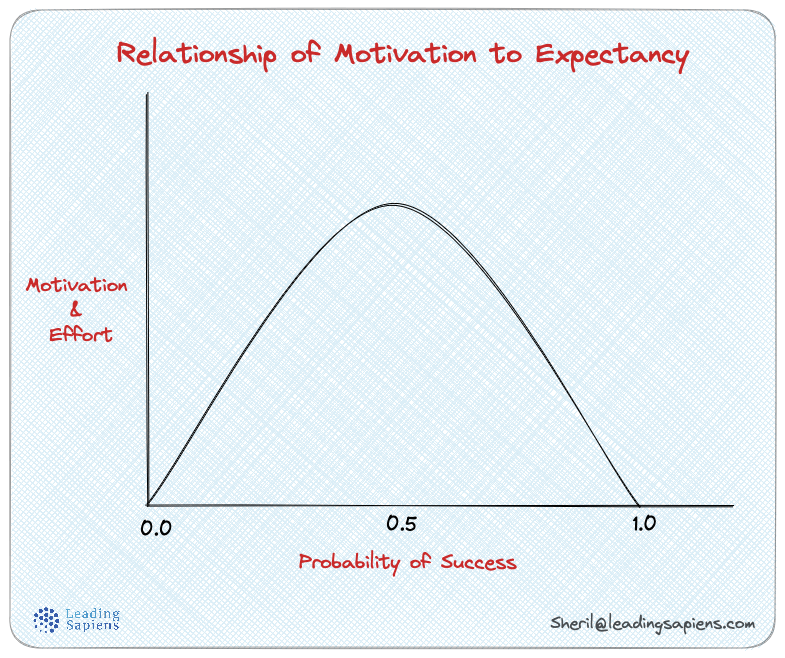

A well-researched aspect of goal setting is that the challenge of our goal influences how much effort we put into it. Everything else being the same, we put in more effort to reach a harder goal than otherwise. We also derive much more feelings of satisfaction and achievement when we hit those harder targets compared to something that was easy to achieve.

However, we have to balance this element of challenge with achievability.

The relationship between motivation and expectancy tends to follow a bell-curve. As the degree of difficulty rises our efforts tend to increase but only up to a certain point. The moment we think our goal is virtually certain or virtually impossible, we are not as motivated and our efforts adjust accordingly.

Balancing high standards with realistic estimates of effort

This notion of setting challenging targets is fairly well understood in management. Good managers excel at pushing their teams by setting high standards in order to stretch them.

The flip side however, of setting high standards, is to regularly communicate what those standards look like and the realistic amount of effort required to hit those ambitious targets.

Bezos calls this recognition and scope.

What do you need to achieve high standards in a particular domain area?

First, you have to be able to recognize what good looks like in that domain.

Second, you must have realistic expectations for how hard it should be (how much work it will take) to achieve that result—the scope.

He gives an example of practicing perfect handstands:

A close friend recently decided to learn to do a perfect freestanding handstand. No leaning against a wall. Not for just a few seconds. Instagram good. She decided to start her journey by taking a handstand workshop at her yoga studio. She then practiced for a while but wasn’t getting the results she wanted. So, she hired a handstand coach. …

In the very first lesson, the coach gave her some wonderful advice. “Most people,” he said, “think that if they work hard, they should be able to master a handstand in about two weeks. The reality is that it takes about six months of daily practice. If you think you should be able to do it in two weeks, you’re just going to end up quitting.”

Unrealistic beliefs on scope—often hidden and undiscussed—kill high standards.

To achieve high standards yourself or as part of a team, you need to form and proactively communicate realistic beliefs about how hard something is going to be.

He contrasts the example of handstands with that of writing Amazon’s famed 6-page memos:

In the handstand example, it’s pretty straightforward to recognize high standards. It wouldn’t be difficult to lay out in detail the requirements of a well-executed handstand, and then you’re either doing it or you’re not.

The writing example is very different. The difference between a great memo and an average one is much squishier.

It would be extremely hard to write down the detailed requirements that make up a great memo. Nevertheless, I find that much of the time, readers react to great memos very similarly. They know it when they see it. The standard is there, and it is real, even if it’s not easily describable.

… Often, when a memo isn’t great, it’s not the writer’s inability to recognize the high standard, but instead a wrong expectation on scope: they mistakenly believe a high-standards, six-page memo can be written in one or two days or even a few hours, when really it might take a week or more!

They’re trying to perfect a handstand in just two weeks, and we’re not coaching them right. The great memos are written and re-written, shared with colleagues who are asked to improve the work, set aside for a couple of days, and then edited again with a fresh mind. They simply can’t be done in a day or two.

The key point here is that you can improve results through the simple act of teaching scope—that a great memo probably should take a week or more.

We humans are not good at estimating how much effort and time something takes, especially when tackling complex, adaptive challenges without pre-proven solutions. Leaders play an important role in managing these expectations.

As leaders, our job does not end with just setting high expectations. It also entails communicating a clear picture of what it will take to meet those targets, aka clear expectations.

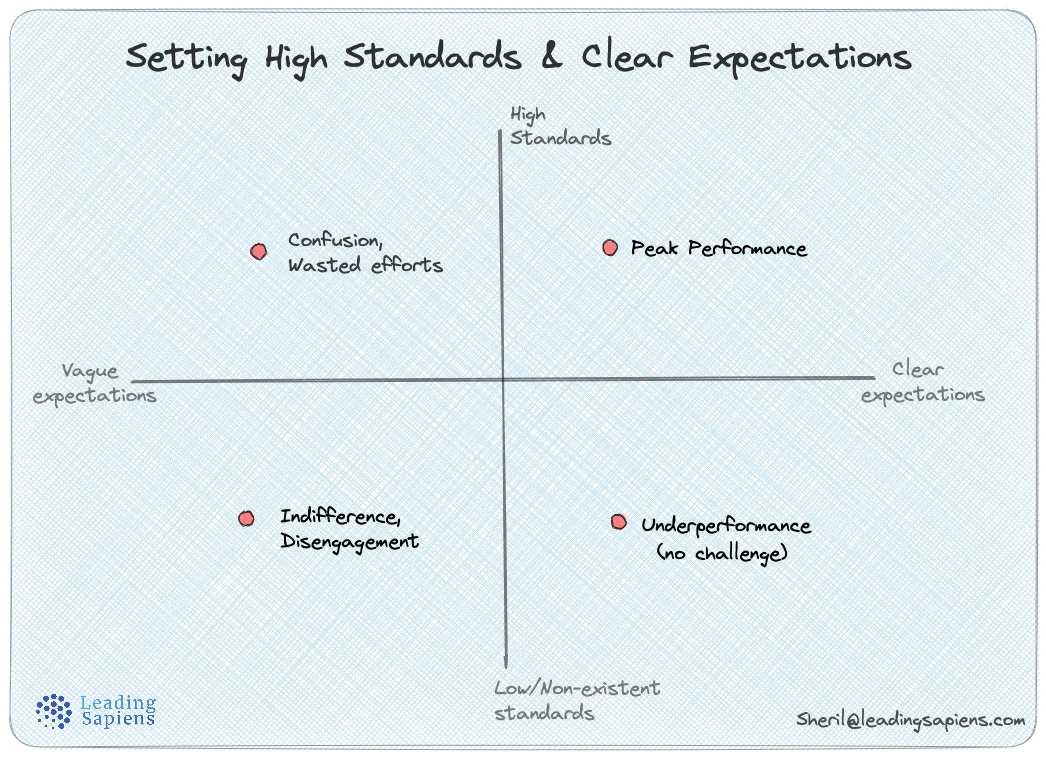

Four quadrants of setting high standards and clear expectations

Thus, the balance between high standards and clear expectations would create four quadrants :

- Peak Performance – high standards and clear expectations

- Underperformance – standards don't challenge or push the limits

- Confusion – wasted efforts due to vague expectations

- Indifference – worse case of vague expectations coupled with low standards

Squishier domains

Also notice how he differentiates between the two examples as one being more squishier than the other.

He’s talking about the difference between technical problems or skillsets which are clearly defined vs that in a complex-adaptive domain where there are no clear answers or clear markers of competence.

Leadership happen to be in the latter. We know when we see it but it's hard to quantify it.

Examining expectations

It’s also worth examining our own expectations about how quickly we expect both ourselves and others to be competent leaders. Are we trying to learn perfect handstands in two weeks?

If it takes 6 months of practice for perfect handstands, what does it take to develop your leadership?

On teachability

He highlights the fact that high standards can in fact be taught and are contagious as a culture.

I believe high standards are teachable.

In fact, people are pretty good at learning high standards simply through exposure. High standards are contagious. Bring a new person onto a high standards team, and they’ll quickly adapt.

The opposite is also true.

If low standards prevail, those too will quickly spread. And though exposure works well to teach high standards, I believe you can accelerate that rate of learning by articulating a few core principles of high standards.

On domain specificity

In another article, I highlighted how collapsing domains is one mistake we make when making assessments of our capability in any domain.

I wrote:

On one hand, the optimist and idealist in us assumes that great strength in one of the domains will carry us in the other two.

On the other hand, the pessimist in us assumes that weakness in one domain automatically excludes us from opportunities requiring more of the other.

We have to resist collapsing the domains and objectively look at our competence in each of them.

Neither approach makes sense but we do this on a regular basis.

Bezos, addresses this idea in the context of high standards:

Another important question is whether high standards are universal or domain specific. In other words, if you have high standards in one area, do you automatically have high standards elsewhere?

I believe high standards are domain specific, and that you have to learn high standards separately in every arena of interest.

Understanding this point is important because it keeps you humble. You can consider yourself a person of high standards in general and still have debilitating blind spots.

There can be whole arenas of endeavor where you may not even know that your standards are low or nonexistent, and certainly not world class. It’s critical to be open to that likelihood.

On skill as a requirement

When managing technical teams aka knowledge work, it is common for someone in the team to know a lot more than the manager or leader. This transition can be hard for people with specialist backgrounds who rose through the ranks on the basis of their technical chops.

But staying on top of everything technically and knowing more than everyone else is a physical impossibility, and does not help with fully leveraging the capabilities of your team. [4]

Bezos addresses this idea of your skill as a requirement:

In my view, not so much, at least not for the individual in the context of teams.

The football coach doesn’t need to be able to throw, and a film director doesn’t need to be able to act. But they both do need to recognize high standards for those things and teach realistic expectations on scope.

Even in the example of writing a six-page memo, that’s teamwork. Someone on the team needs to have the skill, but it doesn’t have to be you.

Often leaders can have the most impact when they are managing the context rather than delving in the content. One way of doing that is clearly communicating the scope and what success looks like.

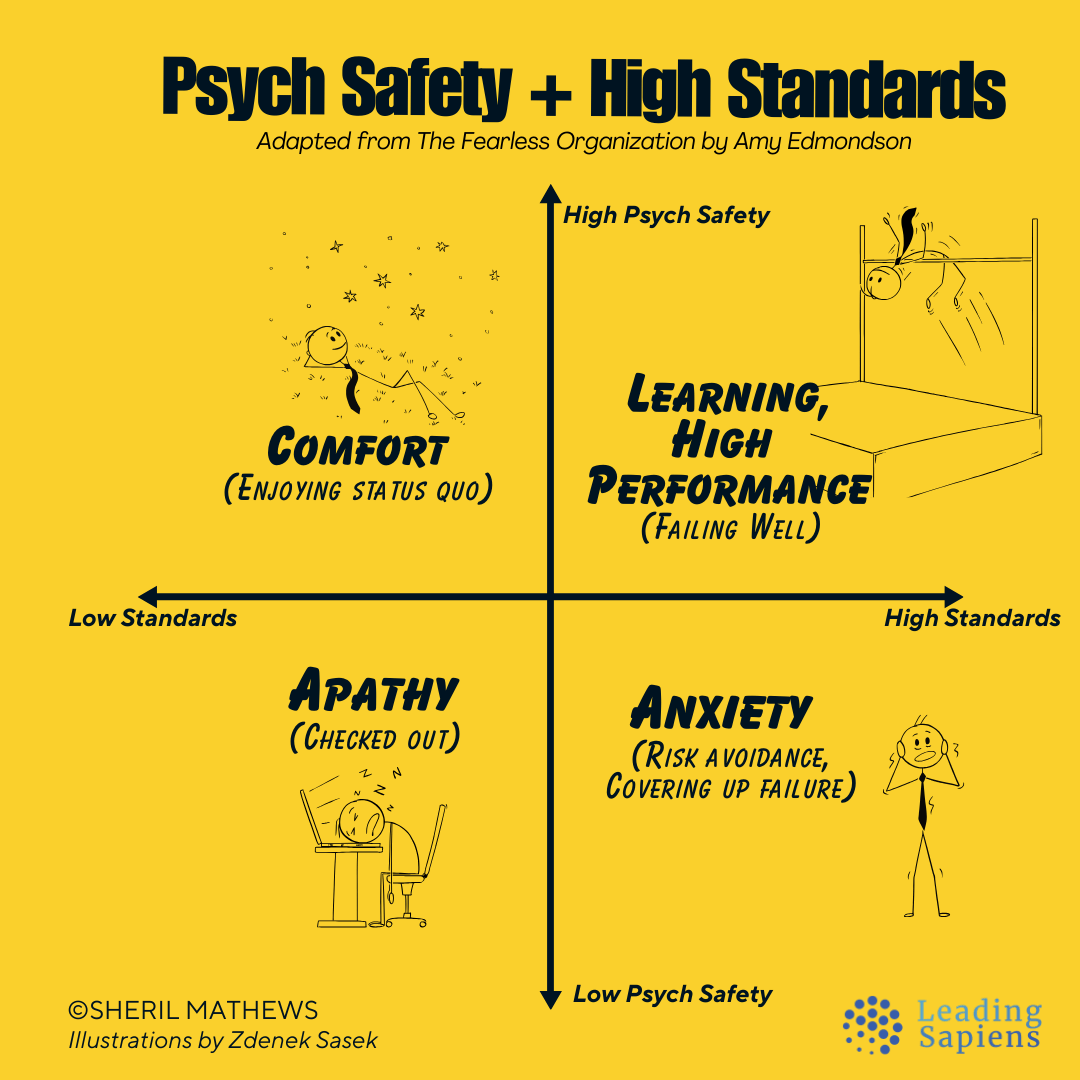

We are much more likely to stay with our goals and reach them if we have a good handle on what it takes. And high standards need to be balanced with psychological safety as well.

Questions to ponder

- Is there alignment between the high standards we have set and our team’s beliefs around scope and the effort required?

- Are we communicating these standards clearly and regularly?

- Do we have a clear idea of what competence looks like? And is everyone on the same page about it?

Further Reading on High Standards

Setting high standards is only one of several frameworks Bezos mentions in his shareholder letters. I collected all of his mental models in one article.

High Standards and Psychological Safety are not opposites:

The article on Transitioning from a Technical Specialist Role into Leadership is where I wrote about the mistake of collapsing domains.

For an exhaustive look at the many dimensions of setting goals and OKRs, check out Effective Goal-Setting Using 14 Different Dimensions.

Sources/References

- https://www.aboutamazon.com/about-us/leadership-principles

- You can find the 2017 shareholder letter in it’s entirety here.

- For a more comprehensive collection of his writings, see Invent and Wander by Walter Isaccson.

- In Leading Geeks, Paul Glen compares this notion to the 400 year old medieval guild system and how we still have remnants of it in our behavior:

Many of our notions are still rooted in the history of the European medieval guild system.

Under the guild system, master craftsmen who had reached a very high proficiency with their work and were able to demonstrate both technical mastery and business success trained other craftsmen in their discipline. Masters were served by journeymen, who had achieved a modest level of expertise under the supervision of their masters. And both masters and journeymen oversaw apprentices, who were beginning their training. The relationship between the master and his subordinates was one of both supervisor and teacher. No one could reach such a lofty level without having mastered all the fine details of apprentice and journeyman’s work.

Today, we still harbor the tacit assumption that this system of mastery remains in place—that managers of a group should be the best trained in the craft and that they are responsible for the training of more junior and less knowledgeable subordinates.

But as technology has become increasingly complex, specialization has rendered this assumption invalid. In the high-tech world, it is virtually unheard of to find a CEO who started out sweeping the floors and worked his way through every job in the enterprise to reach the top of the company.

The range of technology makes it impossible for anyone to know all the details about even one system, let alone know everything about an entire company.