SMART goals is a widely accepted framework coming out of goal setting research. Every other organization uses it in some form with countless articles written on it.

We don’t want to be dumb either, so we go about setting "smart" goals in personal areas as well. This includes yours truly. But looking back at my year, I missed most of them, in spite of following the framework assiduously.

In hindsight, my so called smart goals were actually stupid. What were the critical mistakes and what will I do differently this year?

Why SMART goals are anything but smart

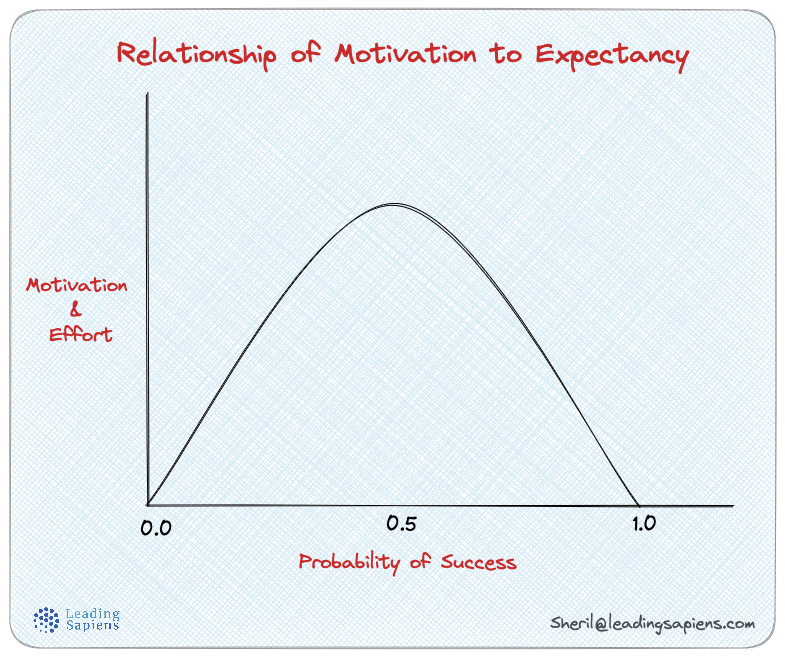

The SMART acronym stands for Specific, Measurable, Ambitious or Actionable or Attractive, Realistic or Relevant, and Time bound. There are as many variations as there are authors. But the underlying ethos of the framework is to leverage the motivation vs expectancy curve to ensure we stay motivated and focused on our goals.

Put simply, effort is sustained and increases the more clearer and more achievable it looks, but only up to a certain point. SMART is supposed to help straddle that optimum balance between motivation and expectancy.

But in an effort to simplify, it ends up doing more harm than good. Consider the following:

- Specificity. Often what we are attempting is vague, especially in the early stages or when operating in complex domains with no clear criteria. Clarity often emerges only in hindsight. Trying to be specific upfront only ends up delaying first action. In contrast, random “foolish” actions can create intelligence that eventually leads to clarity and specific tasks.

- Measurable. The framework is inherently performance based. Many studies have proven that learning goals, rather than measurement, are more effective at motivating intrinsically and sustaining engagement in the long run. Often things worth measuring, like qualities, are not measurable. Measurement also means being narrowly focused while potentially missing out on other feedback that might be more relevant

- Actionable/Attainable. What do you do when the next action is not obvious or when there are too many competing actions? If all you attempt are attainable goals, why bother even setting them?

- Realistic/Relevant. If we stick to only what’s realistic or relevant, it’s essentially binding us to what we already know thus preventing exploration.

- Time bound. In complex, fuzzy arenas we don’t always know how long something takes. Even in well defined areas, each person’s timeline varies based on a variety of factors.

One definition of smart is being adaptive and responsive, but SMART goals are static and restrictive. They assume a mechanical, linear stance instead of the iterative, dynamic, ever changing terrain we face everyday. There is an assumption of upfront knowing and predictability, which contradicts the unknown, unpredictable nature of work and life.

Why my smart goals failed

Why did I fail at most of my goals while doing spectacularly well at a select few? I found common elements to both failures and successes, albeit realizing it only in hindsight. Many of these are obvious and perhaps the very reason I missed them.

1. External motivations

Many of my goals were “shoulds” and “musts” inspired by someone else in some shape or form. In the reality of day to day execution, removed from the clear detached thinking of goal setting, ultimately I fell back to what I already knew, listening to my own voice. Often we already know what’s best for us.

It became clear I didn’t have any intrinsic motivation for those goals. Perhaps setting an intention and seeing if you actually followup is one way to differentiate between extrinsic and intrinsically motivated goals.

Regardless of our awareness, we are already moving towards or away from something. Working towards something or the unwillingness to do so, can give clues into what truly motivates us.

2. Using it as a manipulation tool

Often we set goals because we think if we don't set them we won't do what's needed, or simply because some hustle culture guru has been raving about their "miracle" system. We want it as a forcing function. Instead it ends up being a blunt manipulation tool — it doesn't do what we need it to do, but also creates a mess.

3. Mismatch between perception and reality of what it takes

It’s always longer, harder, and more mundane than we initially thought. We research the destination but forget about the journey, leading to an intimate understanding of the outcome but not the process.

We are prepared to become the next NY Times bestselling author, but not for sitting in front of a blank screen day in, day out, only to realize we don’t in fact like the process after all. And unlike travel, we spend most of our time in the "journey” to the outcome, with an infinitesimal part of it in the actual destination aka outcome.

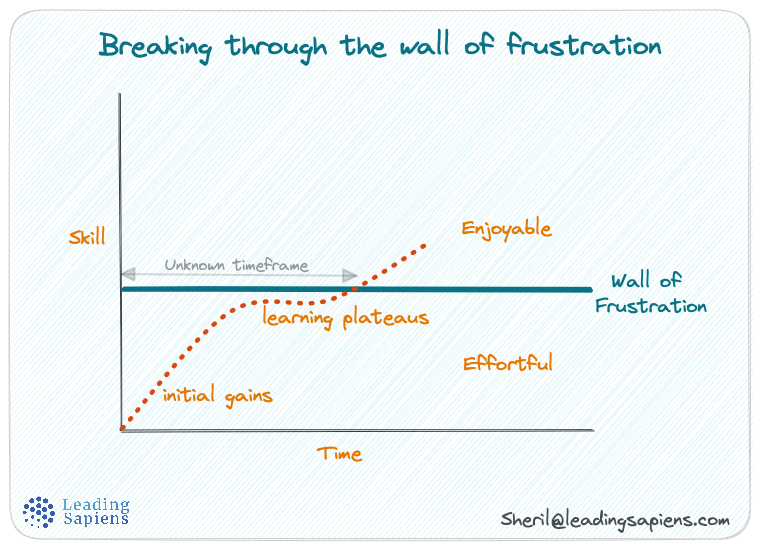

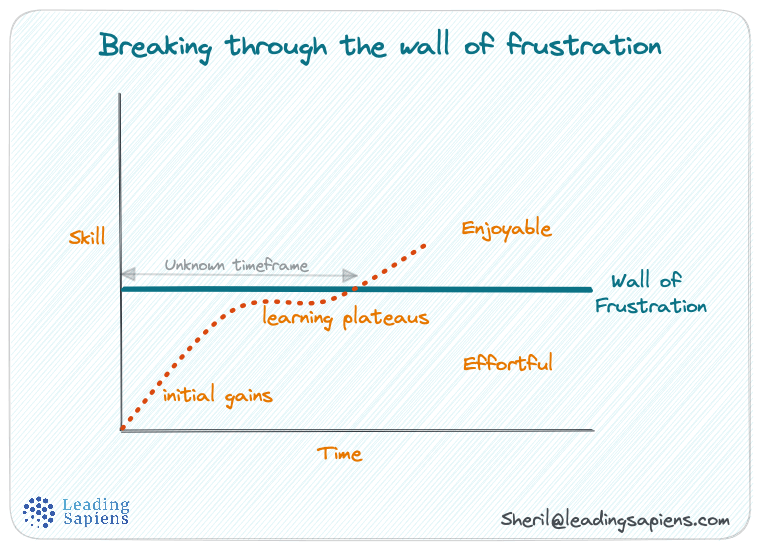

4. Quitting before getting past the "wall of frustration"

We quit before we start enjoying the process. Any new skill is frustrating by definition in the early stages of learning. The challenge is to make it past the point where you start enjoying the skill which then builds on itself.

Intellectually, I think everyone understands this. What makes it more challenging is that you don’t know exactly how long it will take for you. Sticking with something that has a finite timeline is a lot easier than persisting with no clear end in sight.

5. No external scaffolding

Many of my goals didn’t materialize because,

- They required me to act differently from my ongoing daily routines, and

- I didn’t have external systems and support structures to reinforce and support my transition to the new behavior.

Achieving even one of them would have required major changes in daily rhythms. Sustained change in multiple areas while possible, requires a lot more effort and takes longer. People who make overnight changes tend to revert back to their baseline. Folks who are able to sustain change long term, do so because the changes were more integrated with their overall lives or because they pivoted their lives around that change.

Writing resolutions is a first step but also the easiest. Everything is an uphill climb after that. Also, the mere act of writing goals can give a false high that can lull us into inaction. What matters is what follows after day one.

6. No external accountability

In addition to external structures you need some kind of external accountability mechanism. This one’s probably the Achilles heel of personal goals. Accountability tends to be naturally built into work setups, but in personal areas or if you are an independent operator like me, this is a common pitfall.

7. Our estimation of time is flawed

Putting time limits on goals is a tried and tested tactic. But this works well when the domain is well understood and tasks are well defined. Setting arbitrary timeframes doesn't necessarily help in newer complex domains, or something in which we are plain newbies.

Time limits increase pressure and internal criticism. When we miss the deadlines, we forget that we were the ones who came up with the deadlines. It’s better to look at it as closing in on the end goal, rather than having missed a target. This is especially critical if you are new to a domain where you don’t know exactly what it will take and how long.

8. Our mental accounting is flawed

We might be succeeding in some areas, but we don’t see them because of our focus on failures and misses. When we do in fact notice, we’ve already moved on to the next target, thus failing to register the positive in the porous sieves of our minds. Meanwhile we keep replaying the failures thus ensuring they're etched in memory.

Success doesn’t come with blinking lights as depicted in movies. It often comes not clearly delineated and is sometimes too mundane to notice. Some aspects to consider:

- Your definition of “success” might be too stringent.

- Discrepancy between what you initially thought and the actual path is not necessarily a failure.

- Satisficing or reducing standards for the time being is not necessarily bad.

- Taking a closer look at our arbitrary benchmarks can be helpful.

9. Comparing against others

Setting goals automatically means measurement which also means comparison to others who might be “leaner, faster, better”. We are intimate with our own struggles, but only an outsider’s view of others people’s challenges or their inherent advantages. Comparison can be the fastest road to misery, especially when external outcome-driven goals make it easier to do so.

10. Being too rigid

When striving for something, we are constantly evolving and so are our goals. But we pretend as otherwise—a goal that was set 6 months back is not as accurate as my experience and assessment of it today, but somehow I pretend that the person 6 months back was wiser. So instead of revising my estimates, I beat myself up for not being diligent enough.

Consistency for its own sake can easily turn into what Emerson called, a “foolish consistency”.

11. Focusing too much on problem solving

Using goal setting as a problem-solving device rather than a creative endeavor are two fundamentally different approaches. One operates out of what already exists and resolving existing issues, whereas the other is of creating what you want and working towards it. One is bound by the past whereas the second is tied to the future.

Too many of my goals were rooted in problems I was trying to solve. Even if I hit everything I would end up with a "patched up past" rather than a "designed future".

12. Too many of them

Saying yes to something also means saying no to something else. If everything's important, then nothing is.

Too many goals also means lack of focus, lack of sufficient time and attention for something to develop, and scattered resources. You end up quitting before hitting critical mass and momentum.

Key takeaways and what I will do differently

Legit effective goal design is more of a difficult art form and less of a science. Here’s how I am approaching goals differently this year:

- Use goals as a prioritization tool, rather than a motivation or manipulation tool. It's an external construct and reminder mechanism — a compass and beacon to keep you focused rather than a comparison mechanism.

- See goals as a process of natural selection that exposes a lack of intrinsic motivation. Use it as a system to discern and weed out non-inspiring ones. The ones you genuinely care about will tend to emerge over time.

- Stick to only 2-3 major goals at a time, with everything else feeding into or supporting them.

- Differentiate clearly between outcome-based performance goals vs learning-based mastery and maintenance goals. They are fundamentally different in nature and should be kept separate based on the stage of project and your skill level.

- Focus more on process goals and inputs rather than outcome goals or results. One tends to be more in your control than the other.

- For every goal you target, check for impact on existing routines and install external supporting structures. Without this, there’s zero chance of succeeding.

- Regular check-ins with a peer, coach or mastermind group can make a tangible difference.

- Expect it to be long, hard, mundane and replete with setbacks. Anything worthwhile always is, and is a realistic approach to optimism. As James Stockdale put it, "You must maintain unwavering faith that you can and will prevail in the end, regardless of the difficulties, AND at the same time have the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be."

- Stay alert to and account for the “wall of frustration”. Ascertain whether you have crossed it or not. Expect it to be tough going until then. Account for the fact that you don’t exactly know how long this will take.

- In novel, new domains, use goals as a "zooming in" tool rather than a targeting tool. In these cases goals end up being first guesses that you are constantly adjusting and fine tuning.

- Watch for mental accounting flaws. Are there small wins you are missing? When faltering, focus on what you’ve already accomplished instead of what’s left to be done.

- Instead of comparing yourself with others, doing it against past versions of you can be more productive. Lean towards adjustments rather than resentment. You know more about your goals today than you did the day you set them.

- Focus more on creating what you want rather than exclusively solving an existing problem-set.

In complex, novel situations, the “stupid” approach is more adaptive. Once the territory is better defined, then it makes sense to switch to the smart approach. This is akin to the explore vs exploit dichotomy, each requiring a different mindset and strategy.

An alternate approach

In addition to the above, consider the following counter-intuitive but practical strategies based on the realities of getting things done.

Expect it to be mundane. Planning for the challenge of dealing with the mundanity of excellence for long periods of time can significantly increase chances of success. Mundane doesn’t mean drudgery either. Paradoxically, it means enjoying the various mundane aspects involved in the process of getting to your goals.

Go small. Look for small wins rather than the default of going for big bold bets. Can you design for small wins? This goes beyond simple notions of small steps and celebrating wins.

Go negative. Often, the unstated intent of goals is to control outcomes. We don’t want to work toward something and not have anything to show. But what happens when outcomes cannot genuinely be controlled? That's where the ability to deal with uncertainty and ambiguity comes in. John Keats coined the term Negative Capability in 1824, but it's even more applicable today.

Be naive. Setting goals is a clever, sophisticated approach. But often situations require a naive disposition rather than a calculated one. In many situations, being naive can in fact be a positive.

Go deeper. There are many underrated but critical aspects of goals that go unnoticed. Understanding these nuances can make the process more effective and fruitful.

Check for alignment. Ask these three basic questions before setting any goal.

Go for qualities rather than outcomes.